Why is Guy Delisle turning his observant, careful, dispassionate eye upon himself? That was the first question that popped into my mind a few pages into Factory Summers. I thought of the travelogues that had brought him accolades over the years—his insights and recollections of China, a rare peek into North Korea, his last major work, Jerusalem—as well as the volumes dedicated to parenting that still managed to deflect attention away from him and onto those occupying spaces he shared with them.

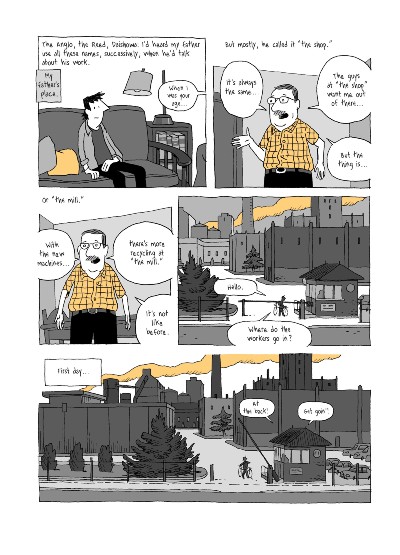

It is only after I finished reading Factory Summers that I realized Delisle hadn’t really drifted that far from his usual stance. Yes, this was more personal, relating as it did to his life as a young man, and his emotional distance from a father who had divorced his mother a long time ago. It still placed him at a remove though, this time from colleagues at a Quebec City paper mill where he worked the night shift as a teenager.

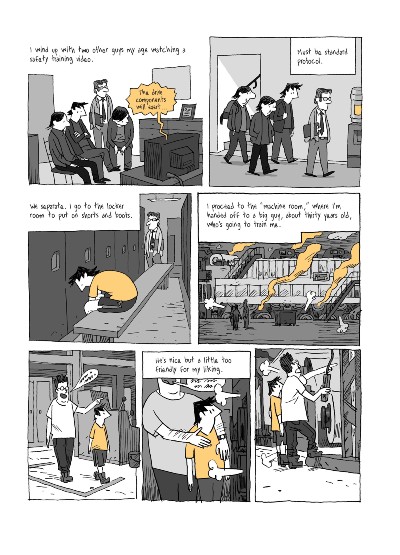

The real action in this book takes place in the minds of men working alongside Delisle. Unlike his travels in foreign countries, these are people who ostensibly share his language and culture, yet manage to communicate in ways that make him feel like an outsider peeking in. They have rituals and codes of their own, and he isn’t allowed to partake of them. Part of this sense of disconnection emerges from his own interests and preoccupations (because being a student of art in a place that celebrates manual labour cannot have been easy), as well as the shadow of his absentee father who happens to work at the same mill, but in a management position.

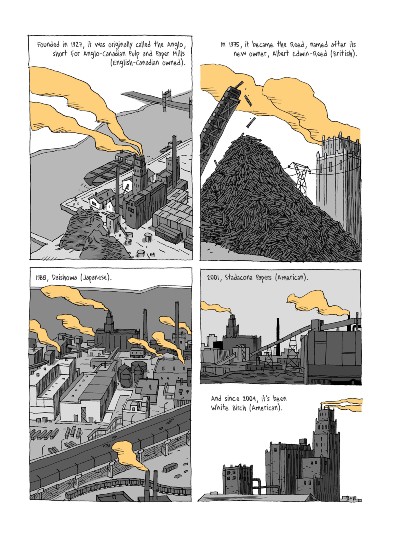

Distance is also conveyed through the clever use of colour; a monochromatic mustard hue that marks only the protagonist or specific points of interest in every grey panel. It works magnificently, lending the book a kind of minimalist beauty.

Delisle also uses his well-honed skills to capture the emotional lives of people around him, with the help of banter, the odd stray comment or rude joke, and gorgeous illustrations contrasting the puny figures of men with the shadows of hulking machinery. The lack of action works in the book’s favour, compelling readers to read between the lines and focus on what isn’t explicitly stated. Why, for instance, must his colleagues sweat in the bowels of the mill, while managers supervise them in air-conditioned comfort? There is no direct indictment of these conditions, but the subtext is as clear as the neat drawings that bring them to life.

It’s interesting how the men refuse to accept Delisle as one of them, even though he seemingly performs the same tasks, using obvious differences based on class to treat him as a casual intern whose life is destined to be lived away from the grime of their permanent workplace. He documents the misogyny and casual homophobia of the time as well, refraining as usual from commenting on why it exists, while maintaining a respectful distance from the men and their troubling beliefs.

What one takes away from Factory Summers is more than just an insight into an artist’s development; it is a carefully nuanced memoir of a time that clearly had an impact on the young Delisle, one that required him to take the time and space required to better process that particular period of his life. I realized, eventually, that it was only by travelling the world and looking at everyone in it that he could finally turn inward and confront a forgotten part of himself.

Guy Delisle (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $24.95 CAD/$22.95 USD

Review by Lindsay Pereira

[…] • Lindsay Pereira reviews the nuanced minimalism of Guy Delisle’s Factory Summers. […]