Not every Beto fan loves every Beto book, but even in this crazed tale of zombies and body horror, he leaves enough of his creative DNA on the scene to reveal the presence of a comics master.

As anyone ambitious enough to call themselves a Gilbert Hernandez completist could testify, Beto’s level of output is showing no sign of letting up, even more than 30 years after Love and Rockets burst onto the scene.

Just the opposite, in fact: his workrate and imagination have burst out of the constraints of the L&R format, leading to an explosion of mini-series, graphic novels and collections in recent years.

Even in the past year or so we’ve already had three and a half books from Fantagraphics (The Children of Palomar, Julio’s Day, Maria M and his bits of Love and Rockets: New Stories #6) and one from Drawn & Quarterly (Marble Season).

And now Dark Horse are getting in on the act, with this handsome hardback reprint of Beto’s characteristically free-wheeling take on the ubiquitous zombie narrative (originally published as a four-part mini-series in 2012).

The story crackles with such chaotic energy that trying to summarise the plot neatly would be like attempting to nail jelly to a tree. However, it kicks off in a world where an insanely addictive drug called Spin has turned almost the entire population into shambling wrecks.

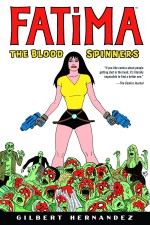

Fatima, the eponymous heroine, has a simple survival strategy; to shoot as many of them as she can through the head – something she does with great relish. The first couple of pages alone see more than a dozen noddles go ‘pop’.

The first half of the story treads fairly familiar ground. We flash back to a year earlier, and Fatima’s previous life as an agent of Operations, a high-tech paramilitary unit ostensibly tasked with stamping out the then-nascent Spin problem.

However, it doesn’t take long for the tale to go careering off-piste. A spell in suspended animation pushes the story into post-apocalyptic conspiracy territory, before it hurtles headlong into what would be categorised as ‘body horror’ if it wasn’t so comically absurd.

Beto has never been one for fan service. Indeed, some of his more extreme work seems specifically designed to alienate those vocal readers who’d rather he stuck to more ‘mainstream’ material.

I have to admit that I don’t always know how to react to his choices of material. When I picked up the first issue of Fatima back in those balmy Olympic days, my antipathy towards zombie narratives left me a bit deflated by it (before I learned to stop worrying and love the bomb).

So how can we reconcile this kind of Grindhouse mayhem with a canon of mainstream work that spans the decades from Heartbreak Soup to Julio’s Day and Marble Season? If we’re prepared to get a bit ‘auteur theory’ about it, we can find of lots of elements here that tie together Beto’s whole, um, oeuvre.

Maybe the first element, which Beto takes to fresh extremes in Fatima, is a willingness to throw the constraints of structure out of the window – a refreshing move in an age when, as scientists have proved, you’re never more than five feet away from a copy of Robert McKee’s Story. The demands of three-act cinematic structure seem to have permeated the whole narrative universe. (And I know this, because – as an MA graduate in screenwriting – I was that soldier.)

However, in the best possible way, Fatima is like nothing so much as the breathless, improvised “and then… and then… and then…” storytelling of a young child – to the point where it almost becomes easier to stop trying to make sense of it all and just enjoy the the ride.

The pace at which Beto works allows him to channel the material directly from his subconscious onto the page without a lengthy spell of self-editorial gestation. His free-wheeling, almost dreamlike approach to this branch of his work is akin to a stream-of-consciousness approach; it provides a welcome dollop of spontaneity in a narrative environment often littered with set-ups, pay-offs, flashing arrows and “As you know, Bob…” exposition.

As the dialogue becomes increasingly corny and the action increasingly absurd, Fatima moves further and further away from the pretence of naturalism and into the heart of the rich and strange Betoverse where this sort of thing happens.

The other thing that marks Fatima out as a trademark Beto work, from the front cover onwards, is the importance of physicality. The striking Amazonian protagonist is the latest in a long line of his characters to have a statement physique that shapes their lives. That extends throughout the book: the staff of Operations are all magnificent specimens, but once the virus strikes, the human form quickly degrades into a chaotic mess.

As Fatima mutates from a zombie shoot-em-up to a frenzy of polymorphic body horror, it provides a showcase for Beto’s gift for the grotesque. As in much of his more esoteric work, the body itself becomes a threat; while it maintains a semblance of order, it’s just waiting to burst out into a dangerous new form.

(Looking at Beto’s other work, even a ‘straight’ narrative like Julio’s Day includes the grim prospect of eruptive ‘blue worm poisoning’, as well as the altogether more grounded horrors of coming back from war as an quadriplegic and the early days of the AIDS epidemic.)

Fatima might lack the humanity of Beto’s Palomar epic or the intertextual rewards of his Fritz B-movie books, but it’s an energetic and joyously uninhibited work that deserves a place on the increasingly strained shelf dedicated to one of our pantheon-level creators.

Gilbert Hernandez (W/A) • Dark Horse Comics, $19.99, April 2, 2014