No-one can remember who any more, but some bright spark back in the day commented that writing about music was like dancing about architecture. So where does that leave Filmish, Edward Ross’s introduction to aspects of film theory delivered in comics form?

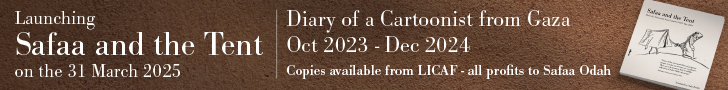

Expanded and reworked from Ross’s original self-published comics and published by SelfMadeHero, Filmish uses comics “to uncover the magic and mechanics behind our favourite movies.”

Expanded and reworked from Ross’s original self-published comics and published by SelfMadeHero, Filmish uses comics “to uncover the magic and mechanics behind our favourite movies.”

Reflecting his background as a film studies graduate, Ross’s observations are backed up by extensive quotes from film practitioners, critics and academics, and expanded upon in extensive endnotes.

Across the seven thematically divided sections of the book, Ross touches on the history, aesthetics and narrative theory of cinema, although he reserves most of his energy for the issue of how film has been used to reinforce dominant ideologies. Laura Mulvey’s influential identification of “the male gaze” is introduced in the opening section, and it never feels like you’re far from the word “problematical”.

Indeed, it’s telling that Ross cites John Carpenter’s film They Live, as his book reads in parts like an attempt to emulate that film’s pair of alien sunglasses, which reveal the subliminal, poisonous ideology lurking beneath the cultural wallpaper of everyday life.

Fortunately, the charm of Ross’s style prevents the book from feeling too much like a finger-wagging lecture. The obvious comparison is with Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, as the author’s cartoony avatar leads the reader through the concepts being analysed.

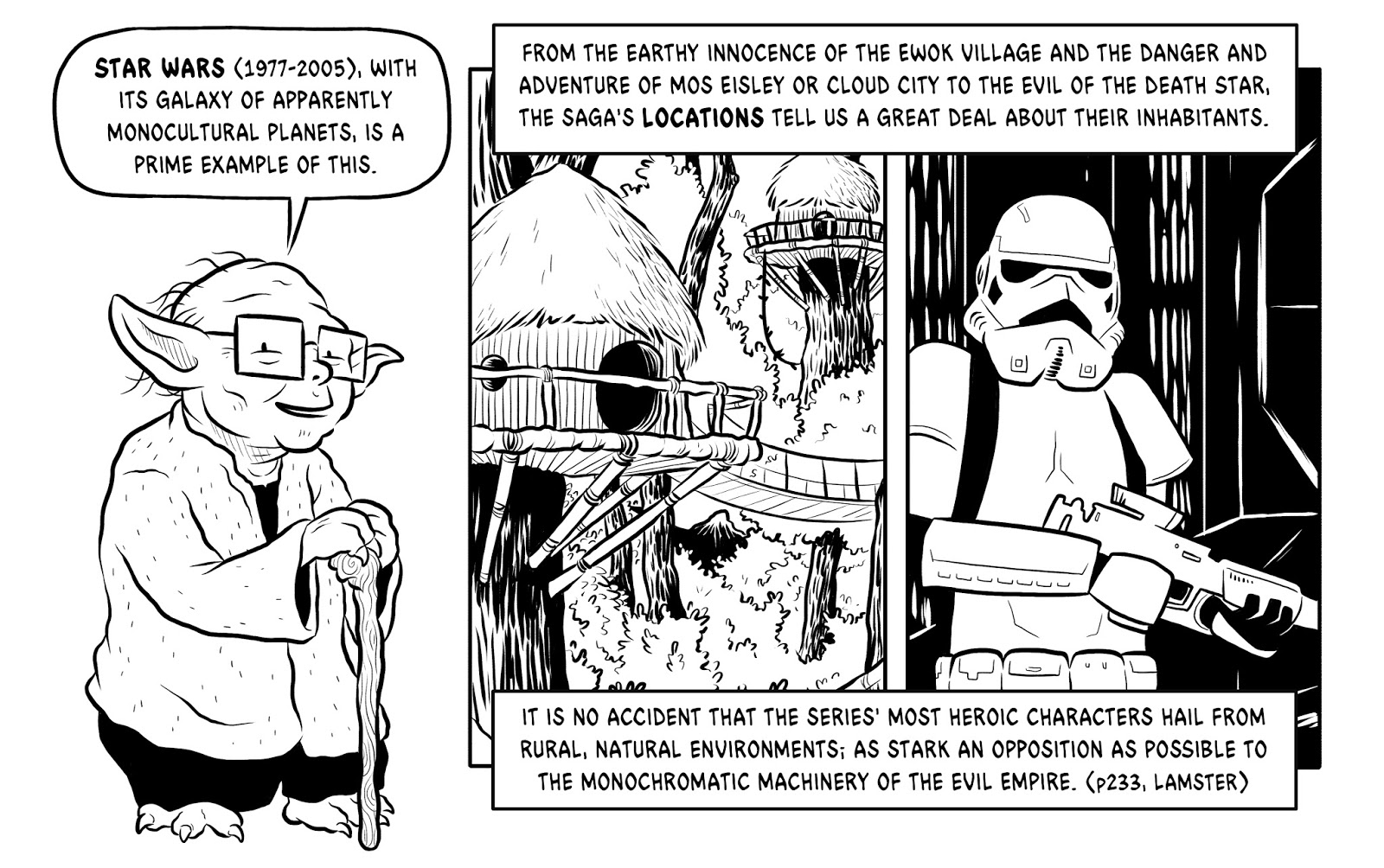

With wit and invention he often inserts himself into the context of his discourse, taking the form of a bespectacled Yoda, a trespasser on the Yellow Brick Road or the victim of a giant mutant ant (trying to fight back with the power of the sun and a magnifying glass).

And going back to the “dancing about architecture” thing, Ross’s recreation of iconic cinematic images demonstrates – slightly ironically – the power of comics to encapsulate information, context and an emotional trigger in an apparently simple single image.

While Ross is admirably thorough in his unpacking of the ideological ramifications of cinema’s cultural pre-eminence, the sections of the book that I found most rewarding were those that are more celebratory about film and the things it can do.

As a big fan of production design, art direction and all things ‘mise en scene’, I particularly enjoyed his chapter on sets and architecture – including some intriguing observations on the Overlook Hotel (in The Shining) and the exploration of urban space in Blade Runner and Die Hard. His chapter on time is also intriguing for anyone interested in narrative theory and creative choices.

As Ross makes clear, cinema remains a comparatively young medium, and one that is in a constant state of tech-driven fast-forward evolution. When he created his self-published version of the chapter on technology and technophobia in 2011, 48 hours of material was being uploaded to YouTube each minute. By the time he was researching his updated version for this book in December 2014, that had leapt to 300 hours a minute.

With its endnotes, filmography and bibliography, Filmish is an accessible and pleasing entry point into the world of film studies. However, there clearly remains plenty more to be said – and Edward Ross would be a very welcome voice to say it.

Edward Ross (W/A) • SelfMadeHero, £14.99