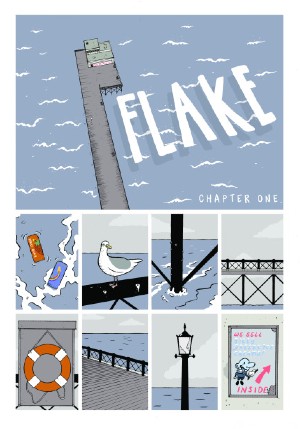

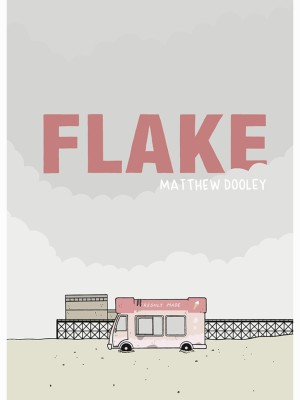

There’s something of the psychogeographical to the opening of Matthew Dooley’s Flake. Dooley, of course, is a Jonathan Cape/Observer/Comica short story competition winner and a prolific fixture on the UK small press scene in recent years. As Dooley’s debut graphic novel opens we silently view the deserted environs of a British seaside resort, its once proud glories lost to time, and its anachronistic attempts to cling on to relevance seeming pitiful and pointless. It’s a fitting opening to a tale of ice cream man Howard “Captain Cone” Grayling whose life has similarly stagnated, bound by family tradition to a vocation with a dying business model in an overcast Northern town, and no prospects beyond a slow and steady decline.

Dooley is a comics craftsman whose work has long deserved far greater recognition. His laid-back wit often wallows in existential angst, digressing into bizarre flights of fancy that amuse and bemuse in equal measure. Catastrophising, his most recent self-published comic, is the perfect example of the kind of worldweary reflections on modern living that have ensured his droll, philosophical meanderings have become essential reading since he first came to prominence in much missed anthologies like Dirty Rotten Comics and Off Life.

Dooley is a comics craftsman whose work has long deserved far greater recognition. His laid-back wit often wallows in existential angst, digressing into bizarre flights of fancy that amuse and bemuse in equal measure. Catastrophising, his most recent self-published comic, is the perfect example of the kind of worldweary reflections on modern living that have ensured his droll, philosophical meanderings have become essential reading since he first came to prominence in much missed anthologies like Dirty Rotten Comics and Off Life.

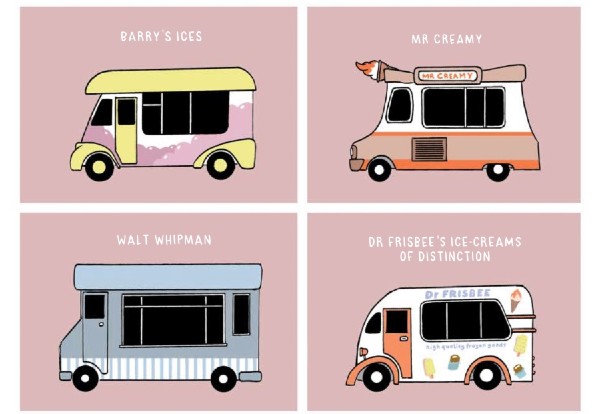

Howard’s life as an ice cream van owner is a quietly unambitious one. The highlight of his day is doing the crosswords for a couple of hours before work begins or chatting with local museum worker Jasper, a failed TV quiz show contestant and ardent campaigner to have the local downgraded hill reclassified as a mountain. This sedentary lifestyle is about to be disrupted however when rogue ice cream vendor Tony Augustus re-enters his life. The mercenary Augustus has swept through the North West of England, dispatching such industry legends as Professor Scrumptious and Dr. Frisbee’s Ice Creams of Distinction in his wake, and subsuming then into his icy empire.

But Howard’s rivalry with Tony has a more personal element. Because this predatory purveyor of frozen taste sensations, who is determined to put him out of business and claim Howard’s father’s patch for his own, is also secretly his half-brother…

In Flake, Dooley’s ability to place the abruptly incongruous within the banal and the unremarkable proves once again to be the greatest strength of his comedic approach. He takes a traditional narrative structure as a starting point and then peppers it with anecdotal sidesteps about the residents and history of Howard’s home town Dobbiston that allow him to exercise the more extravagant parts of his imagination.

While Howard’s story is at the forefront of Flake, frequent digressions fill us in on some of its stranger characters and odder events. The local hero commemorated by a statue who manipulated a confusion in names to dine out for years on his rep as one of Shackleton’s South Pole explorers; the old ladies whose hobby is going to strangers’ funerals; and the local pet photographers whose specialism in historical animal re-enactments ended in bizarre tragedy.

While the deadpan humour is arguably the most noticeable element of Dooley’s delivery Flake is far more than just a bleak comedy. As Howard’s struggles with Tony’s bullying continue, and the latter’s campaign of terror progresses from press manipulation to threats and intimidation, it becomes clear that there are deeper layers to this story. It’s also a very delicately realised tale about friendship, support and the people we surround ourselves with. In his obsession with crosswords Howard seems to be looking for a sense of order and logic that he cannot find in his own life, providing an interesting parallel with Tony whose world has structure and purpose but is lacking in the very human qualities that define Howard.

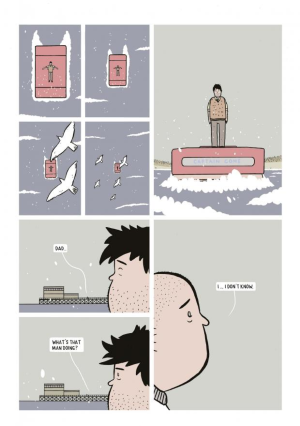

Dooley has always been a subtle visual storyteller, the inherent sophistication in his use of the form easier to miss for his prioritisation of craft over ostentation. The monotonous pacing of Howard’s life, for example, is carefully echoed in tightly structured pages where very little variation can occur from one panel to the next. Passages of time can be set against each other sequentially, visually intersecting to give us multiple perspectives on scenarios while his muted use of colour is an intrinsic part of the book’s atmosphere, heightening both mood and theme. One section where Howard and friend Alex play crazy golf is particularly clever in its realisation, creating panels in vignettes of place and time with inventive relish.

But it’s in the quieter moments of Flake where Dooley reminds us of how nuanced a storyteller he is. Here it is what is left unsaid that ironically speaks the most eloquently about Howard and his struggles; in these gaps in between exposition and dialogue the core emotional truths of his situation hit home. Dooley communicates so much in these interludes about Howard’s existence and his relationship with his immediate environment through a sublime sense of pacing, character expression and body language.

For longer-term fans of his work there are a couple of in-jokes that will delight with their implication that Flake takes place in a wider shared “Dooleyverse”. Ultimately though, Flake is proof positive that Matthew Dooley’s comics are the perfect blend of absurdism and humanity. A triumphant debut for one of UK comics’ most underappreciated rising stars.

Matthew Dooley (W/A) • Jonathan Cape, £18.99

Review by Andy Oliver