Legendary cartoonist Adrian Tomine has a wry endorsement of Edward Steed at the back of this, the latter’s debut collection. “I met Steed years ago at a fancy New Yorker cocktail party,” he writes. “He was the one person who seemed even more ill at ease than me, and I instantly liked his beautiful, funny, scratchy cartoons even more than I already did.” It is a pithy description that is probably closer to the bone than one would imagine, if Steed’s humour is anything to go by. One can almost picture him in a corner, hidden behind a curtain, making notes that are then transformed into acerbic visual gags on paper. It’s probably why flipping through the book sometimes feels like a guilty pleasure.

Regular readers of The New Yorker may recognise a Steed cartoon instantly by now, given the frequency with which he has been appearing there since debuting in its March 2013 issue. He obviously has that certain something, a je ne sais quoi that separates New Yorker cartoonists from the merely talented lot waiting in the wings for their shot. Maybe it’s about the confusion with which one takes in a cartoon, wondering whether to gasp in surprise or laugh out loud.

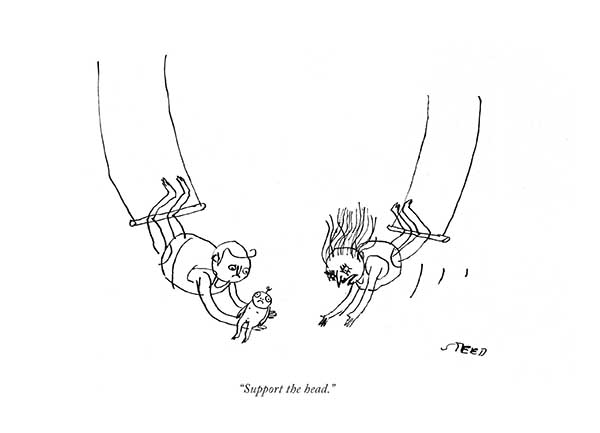

Consider one of Steed’s more recognisable cartoons involving two trapeze artists trying to pass a baby between them. “Support the head,” says the female to the male. Or the one featuring people behind a desk, handing out fake smiles to miserable folk as they walk past, which wouldn’t seem out of place framed outside the conference room of any large organisation. One gets the sense of being in on a joke, without being entirely sure what the takeaway is. It is unsettling, which one suspects is also what helps New Yorker editors make their choices. Steed’s panels have a premise and punchline set up within the same space, leaving each cartoon open to interpretation or misinterpretation.

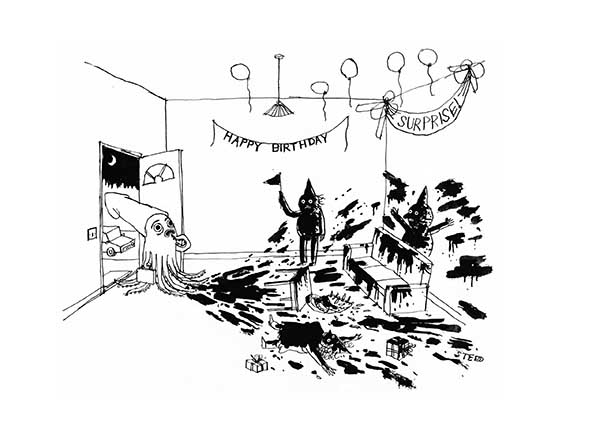

It’s interesting to think about where these ideas come from. Steed once described his process thus: “I sit down at a table with some blank pieces of paper and draw for a while, seeing what comes up. Sometimes it’s not much. I’ll make lines and shapes on the paper, then turn them into things and characters. Hopefully, a joke will emerge.” It is a disarming comment that contradicts the results, because he is clearly someone who has studied the masters of this form closely. It would be churlish to look for the influence of Edward Gorey or Gary Larson, but their shadows flit undeniably across his work, sometimes in the examples of anthropomorphism, at other times in the recognition of something that happens to be simultaneously mundane and absurd.

Steed has openly cited New Yorker alumni like gag cartoonist Charles Barsotti and Saul Steinberg as influences too, while claiming that everything he does is “kind of a glimpse of my subconscious.” After a point, it doesn’t matter, because this is an original voice who deserves to be treated as such. Why look for how the magic trick works?

Ultimately, one walks away from Forces of Nature with gratitude, not only because of how entertaining it is, but because of how one can tell that Steed is only going to get better. His point of view is brutal, but unique. And in a world where lines between the normal and fantastical increasingly blur, it feels as if it is people like Edward Steed who will emerge as soothsayers.

Edward Steed (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $24.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira