“What is a comic?” is not that different a question from “what is art?”, although it may be debated less often and by different people. Don’t shoot me if I say that neither of these things really exist (comics and art) in that they aren’t concrete entities that it is possible to define but rather, like other super important things like love and feminism, they are shifting, nebulous, cultural economic constructs. They is what we think they is if they is anything. Which is why we seldom agree on what it is they is we think they is.

This is also why Google image results for ‘art’ don’t match gallery walls, why every year they publish more bloody articles about how comics are not just about superheroes (because this is still news to some people apparently) and why when you ask a creative person to define what they do they give you that look. Because they don’t know how you define words like “comic”, “art”, “illustration” or “adult”, so they don’t know what pictures you’re going to get in their head when they use them. A lot of people, sadly, haven’t read Scott McCloud.

Why have I stepped so far back to introduce this interview? Because in the big Venn diagram of creative pursuits Gareth Hopkins sits in an overlap that is at once niche and universal, that of abstract comics. He’s not the only person to explore this territory (as he was annoyed to discover in 2009) but if you want to try and bend your head around those big (unanswerable) questions from the first line there, his work is essential existential reading.

Christian Blanken S/S 2012 for Amelia’s Magazine

I first met Gareth not long after he began his foray into abstract comics, but I didn’t know it at the time. We were both in Amelia’s Compendium of Fashion Illustration together in 2010 (above), and we worked together on some other, mostly fashion related, projects for Amelia Gregory over the following years. We were both fitting art and illustration practice around real life and day jobs and neither of us were particularly naturally inclined to an interest in fashion. But REAL artists (which we both obviously are, I’ll stop talking about myself soon, sorry) are always open and responsive and take inspiration as it comes (plus drawing clothes is a lot of fun).

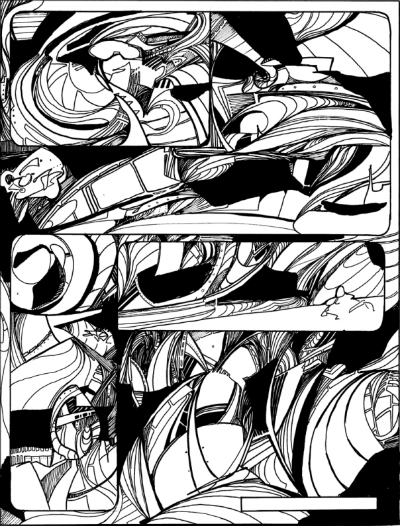

I kept the sort of long distance tabs on Gareth’s work that one does on one’s friends when one has a lot of friends that make things, but came back into focus in 2016 when he was crowdfunding The Intercorstal: 683 and I became instantly obsessed with what he had done using specific comic pages as inspiration for fully abstracted artwork. In a review in The Quietus at the time I called the work “a brilliantly pure expression of what post-modern creatives are capable of” which I think Gareth was quite pleased by.

683 is basically the bastard child of a love affair across the barricades of the American cultural war that waged in the 1960s between abstract expressionism and pop art, with a healthy sidewise glance at process art and Dada. I love it so much because it sits unapologetically in this contested territory, combining approaches that seem a million miles apart and still existing as an accessible and attractive little comic book.

From The Intercorstal 683 note the empty box in the bottom right corner, anticipating text that doesn’t yet exist. Or something.

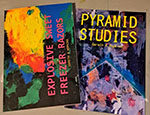

In his most recently published project, a collaboration with Erik Blagsvedt called Found Forest Floor (about which more later) Gareth has moved a bit further from what we think of as a comic in terms of the subject matter and aesthetic, but closer because of the inclusion of words, albeit what appear to be nonsense words, provided by Blagsvedt. The book is a beautiful thing and utterly strange. Because this is Broken Frontier, not some wanky art site though, I wanted to start by asking Gareth about his comic book past.

BROKEN FRONTIER: What was your relationship with comics growing up, and which titles had a big impact on you?

GARETH A HOPKINS: When I was in primary school I’d have been reading The Beano and The Dandy on and off for sure but I don’t think they left a very lasting impression. When I was ten though, my Mum bought me a copy of 2000 AD on a cross-Channel ferry and it blew my world apart. I mean, on the surface level I’m pretty sure it was the violence and the garish visuals that hooked me in, but over time a lot of its underlying messages had a quiet but profound effect on me.

Essentially it taught me that The Rich are the baddies and deviance and difference are to be encouraged. Then later, when we moved out of Wales and newsagents had a bit more choice, I started reading the Batman and Spider-Man digests that were being put out. The first US comic that really made an impression was Spectacular Spider-Man #200, which snuck into my local shop because it had a shiny cover — Sal Buscema’s art in that had a really long-lasting effect on me.

Your work tends to live in a territory which is connected closely to comics, but doesn’t resemble what most people would consider a comic book. Can you briefly outline how you categorise your work, and how you came to abstract comics.

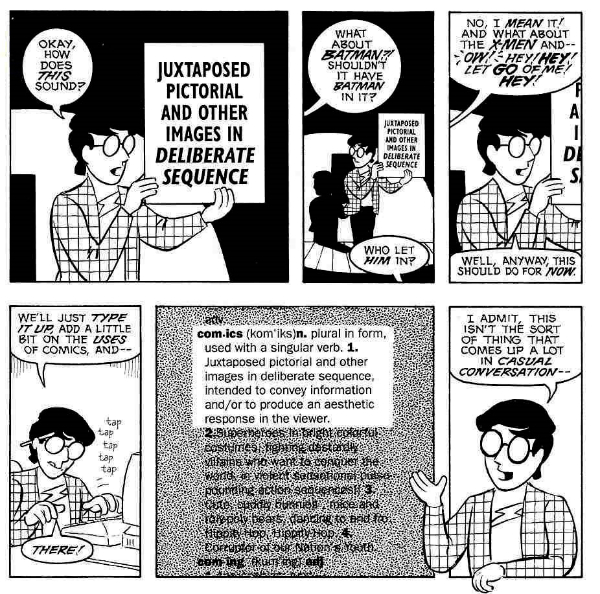

I’ve taken to calling myself an “Abstract Artist who makes comics”, as it’s sort of the quickest route to where I want to get to in a conversation. As to how I categorise my work, that comes down to how people judge what a ‘comic’ is. I think a lot of people, if asked what a comic was, would say something along the lines of ‘A story told through sequential artwork framed in panels which have word balloons and captions to carry dialogue and supplementary description’… I mean, maybe not that exact wording, but those elements. Whereas I think you can tell something’s a comic if the person who made it intended it to be a comic.

[Interviewer’s aside: Guys, I did say not everyone has read Scott McCloud. (sequence from Understanding Comics, 1993 above) Gareth’s definition sounds a lot closer to the definition that many people favour for the whole of ‘art’. Which has a nice sort of symmetry.]

As to how I came to Abstract Comics… it was entirely accidental. I was doing a lot of mailart at the time and not at all thinking about comics, but then sort of accidentally tripped into starting a comic. My influences on the first fifty pages of the project were Surrealism and Dada and vague ideas around ritual and art being somehow linked that I picked up by visiting the Adam Chodzko retrospective at Tate St Ives in 2008 (again, that was by accident, sort of).

At the time I thought I’d invented something brand new and was sharing pages to Deviantart to absolutely no interest from the world at all. And about a year later I found out Fantagraphics had put a whole bloody book of Abstract Comics out (Abstract Comics: The Anthology, 2009) – which was yet another hard lesson in the fact that pretty much everything’s been done before, and often better. And from that point, it’s been playing about with ideas and shapes and different ways of generating pages.

What have been your major projects in abstract comics so far, and how do they differ from each other?

Right. So there was The Intercorstal, which was the first 50 or so pages I did. There was a loose narrative of an alien trying to fight his way out of a psychedelic dimension, and had a number of visual themes like hands and forks and eyestrips. Then The Intercorstal 2 which was an attempt to make a more cohesive body of work, and it was during ‘2’ that I started mixing in pages made by abstracting existing comic pages that I liked – a lot of 2000 AD stuff, the odd smattering of X-Men and Spider-Man, too.

That led to The Intercorstal: 683 which was a conscious effort to take everything I’d worked out through abstracting other people’s work and make a whole cohesive published thing. During making ‘683’ I was approached by Projektraum 404 in Bremen to do something, and came up with After Smith, which reinterpreted 10 pages of comics written by John Smith (this was especially gratifying personally as it became an unintended review of his career via the essay that Tom Whiteley did in support of it).

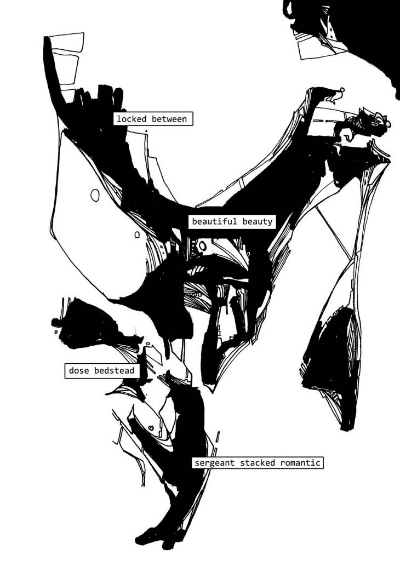

From Found Forest Floor

And now Found Forest Floor. I was approached by David Quiles Guilló of Abstract Editions to collaborate on something with the poet Erik Blagsvedt. The three of us talked about it over email and came up with the idea that I’d build up a bank of pages of art and we’d add Erik’s poetry Marvel-style to it (I don’t think we thought about it as Marvel-style at the time but that’s essentially what it is). We started with the title, then I went off and spent a few months churning out art.

It started off as solid abstract comics of the things around me – two reasons for that: 1. I didn’t want to repeat the same tricks from ‘683’ and After Smith and 2. It meant I could work a lot quicker and more instinctively. After the first 50 pages David suggested I work looser again, outside of the rules of ‘comics’, so I went and broke the 50 pages up in Photoshop to dramatically increase the amount of negative space, and from that foundation printed them all out, worked over them in black and white ink, scanned and ‘shopped them again, then repeated the process. I absolutely lost track of where I was, so just carried on via instinct, and somewhere along the way started working into the pages a drawing that my daughter had done.

Once I’d done 260 pages or so, I arranged the pages by what I saw as themes in them, then used that to inform a kind of narrative flow through 250 pages. Erik used that as inspiration for 50 pages of poetry, and then I used my rudimentary lettering skills to spread that poetry throughout the book. The text in Found Forest Floor is in the same order that Erik gave to me, but I chopped it up into phrases that I thought would work. That all got sent off to David, and he did a fantastic job of editing the book — the few suggestions and changes he made were incredibly on-point. And then we released it.

I see what you mean, but for me when I looked at the book, I was intensely curious about the process, so it’s good to find out more. Reading on intercorstal.com about how Erik used “cut-up and diastic techniques to create batches of words that he liked, which were then compiled into blocks of text.” also excited me. I think the deliberate process vs. unconscious/chance creative elements of the work is important to at least hint at, as I say later these things are so seldom explained on gallery walls.

How have you found self-publishing and what methods have you used in this area? How do you spread the word about your work?

I’ve found self-publishing hugely rewarding, but hard work. Most of what I’ve released has been printed by me and put together with a long arm stapler. For a long time I would send pages off to a friend to turn into a PDF and then print that, but I’ve since found it much easier to knock it together in MS Publisher. Publisher is terrible, I know, but it’s quick, and that suits me. I Kickstarted ‘683’ and got it printed properly by ComicPrinting UK. My feelings about the process of Kickstarting it still haven’t settled – it was very stressful, and had an adverse effect on my life, but at the same time I shifted a bunch of comics via it and the process of promoting it increased my profile a fair amount.

Spreading the word is mostly through Twitter, I reckon. Any traction I gain on Instagram is mostly through people I know from Twitter, and Facebook is pretty useless for actually selling anything. I’ve been lucky enough to have been invited on to The Awesome Comics Podcast a couple of times now and that helps a lot. And then there’s stuff like this, where I wang on far too much about myself.

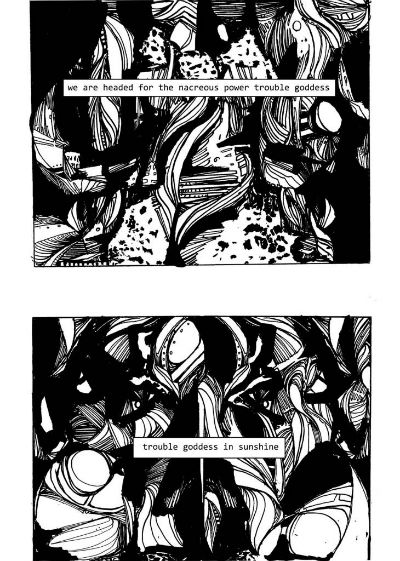

From Found Forest Floor

There’s an argument that good art requires a little work from its audience, but gives back tenfold what time and mental effort it’s viewers choose to invest. Found Forest Floor can be read in a number of different ways. An active reader may observe a tension in the language centres of their brain which contain a tacit awareness of a number of visual grammars, by which I mean that we’re used to reading different types of media differently.

It looks like a comic – but are you able to read it like a comic? Not easily at first. I found that initially after my brain realised the images and words did not have a clearly readable narrative, I was reading the words first before the pictures, like you do with a poster, my brain tapped into that design grammar. Then I got distracted by the pictures and read those separate to the words, like you look at a painting in a gallery before you read the spiel or even the title. I was leafing through at the speed that I am used to reading comics, and very much enjoying the separate semiotic segments of text and image.

I’ve had a hard time with whether Found Forest Floor is a comic or not. It definitely uses the language of comics, in how the text is broken up into captions and where there are panels, to be read within those panels. But to me it’s not doing the job of a comic, in ways that my previous work has. I’ve just been calling it ‘a book’ because it feels like a truer description than ‘comic’ or ‘novel’.

Blagsvedt’s poetry, I realised, is a similar beast to your art. I have been used to the enjoyable experience of immersing myself in the lines and shapes of your abstract comics, letting my subconscious pull out meaning and pictures at times, and only motion and mood at others. Here the words do that same thing, a stream of symbols that our brain cannot resist reading according to the rules of prose, so that meaning peeks out subjectively wherever a hint of grammar exists, and sometimes where it doesn’t.

I’d not realised that me and Erik were doing similar things but in different media until you said it, but you’re absolutely right. I think that’s why we’ve never talked explicitly about how we’d work together, because we just sort of understand what the other person’s doing and allow them to get on with it. We’ve really brought out the best in each other, I think.

All this talk about subconscious meaning and subjective grammar hints does sound pretty pretentious, and like a lot of art that looks simple on first glance but hides a wealth of potential readings, it does require a bit of work and a bit of willingness to be a bit pretentious. Is treading that thin line something you are aware of?

This was the first project where I’ve not worried if I was being pretentious, and pushing the idea of ‘art’ too hard. All my other stuff I’ve felt a real tension with, but this all just felt very natural once I’d hit the right seam. It might be because Erik, David and I all had a shared but undiscussed understanding of what we were aiming for, and never had to explain it at all. That understanding’s actually put me on the back foot though, because now that it’s done I don’t really know how to explain what it is we’ve actually done.

Let me give it a go: Both of you (Erik and Gareth) are building on Modern Art traditions in abstraction and poetry and the territory between, using techniques that have been honed by generations of paid up members of the art intelligentsia, the kind of thing that is so seldom explained on gallery walls, but that when it works well speaks straight to the hind brain and doesn’t require it’s audience to read any manifestos (when it doesn’t work well it feels not only pretentious but esoteric and plain old stupid and annoying). The process is part of the art, but you don’t necessarily need to be able to see it to appreciate the outcome. What you’ve done is put all of that into a little white paperback with words and pictures in. A comic.

This is exceptionally nice to hear.

From Found Forest Floor

After giving in to instinct and reading words first and then pictures first, I decided to fight my brain, and slow down, and really read this comic like a comic; considering the pairings of word and panel sequentially, using my comics literacy. It was a bit hard, to make my brain do that, I don’t know if it is for everyone, but it was rewarding. If I was more musical then I might find it easier, because the layering of each part of the collaboration is quite like the combination of instruments or lines of melody in music. Except when you listen to music you don’t usually have the option of examining each track in the soundscape separately, you have to listen to them combined. You can read it at your own pace and you can slow down and stare at a panel for a while, or you can flick to the end.

When I lettered this, I was actually thinking a lot more about music than I was about comics, so for you to have picked up on that made me spin a little. I was talking to Kek-W about it, and the best description I could come up with was that I wanted the book to read like the sound of a piano falling down stairs.

I could probably write pages and pages on how someone might go about reading or interpreting Found Forest Floor but I’m actually going to refrain for once.

I suppose one can read it in a variety of ways, some of which we’ve already discussed. You might choose to dip into it at odd moments like an I Ching or pocket bible, to find a zen space of strangeness in this manic world that demands narrative. I haven’t yet read it sequentially front to back, I didn’t have the attention span.

I think taking individual pages of Found Forest Floor, or sections at a time, can be rewarding if you’re in the right mood, but I’d encourage anyone reading to try and do the whole thing in one go, or at least end-to-end. When I worked on it, both creating and editing, it was in sections or pages at a time, and hadn’t actually read it through until the week after we’d released it and it was a very surprising experience. It has an unsettling, but not unpleasant, cumulative effect. After I’d read it I messaged Erik in all-caps and he’d had the same experience I had. At some point it took on its own life. Tony Esmond has described it as the book reading you, which is as close as I could ever hope to get to describing it.

Not sure what happened to refraining. It is a great achievement as a piece though, however you choose to experience it.

I never expected to be in the position of encouraging people to read something I’d done purely out of how excited I am by it — I don’t know if that reads right or not. It’s a weird place to be… recommending it to people because I enjoyed it rather than because I made it? I don’t know. It really is something else.

That sounds like a great place to be, and maybe one you can reach only by finding that letting go that comes from both collaboration and integrity or a willingness to engage with art/comics on a level without fear and judgement. This may not be an approach that should be encouraged in creators aiming to produce narrative readability, but who knows.

Found Forest Floor is now available to buy via print on demand from here Find out more about his work on his site here and follow him on Twitter here.

Gareth Hopkins and Erik Blagsvedt will also have Found Forest Floor work on display at the next Young Blood Initiative showcase between the 21st and 26th Sep in Camden.