A warm nostalgia for early experiences of video games is a common phenomenon, and Edward Ross’s begins in Gamish with his brother’s venerable Atari ST, 1985’s rival to the Commodore Amiga. It may have been another 20 years before he returned to the world of gaming with the purchase of an Xbox 360 but this book is evidence that he has played a lot of video games since that day.

A warm nostalgia for early experiences of video games is a common phenomenon, and Edward Ross’s begins in Gamish with his brother’s venerable Atari ST, 1985’s rival to the Commodore Amiga. It may have been another 20 years before he returned to the world of gaming with the purchase of an Xbox 360 but this book is evidence that he has played a lot of video games since that day.

Ross is a natural educator, and so we get a short treatise on the importance of play and of games in human history across many cultures. He traces the roots of chess in China, Japan, Persia and India fast forwarding hundreds of years to the Mechanical Turk in the 18th century, billed as a chess machine that in fact housed a skilled player hiding inside, controlling the game with magnets levers and pulleys. Moving through early heroes of computing such as Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace he arrives at Alan Turing’s work which included the first computerised chess program (too complex to run on any computers of the time, he could only simulate it himself performing his own calculations). As early computer scientists tried to develop artificial intelligences to play games, this provides the perfect segue into the early history of modern computer games – Spacewar, Pong, Space Invaders – and a cultural phenomenon was born.

Gamish credits Nintendo with the birth of the idea that a game should have some kind of story and characterisation, rather than merely a blob representing the player. This is a significant evolution for one of Ross’s central ideas, the way games allow us to experience being another person. This is a development of an idea he previously explored in Filmish, and the way we can see ourselves in films is amplified in games as we are participating in the experience of the other rather than just watching.

Of course, like all forms of media, games represent many perspectives and attitudes. Ross is critical of much reductive, simplistic characterisation in mainstream games, with sexist and racist undertones, whilst referencing many interesting indie games that take different stances.

There’s a curated selection of games he identifies as emotionally affecting as a result of telling true human stories, such as Depression Quest and That Dragon, Cancer. There are limits, however. He looks at Clouds Over Sidra, a virtual reality documentary of life in a refugee camp in Jordan, and observes that some critics see this as high tech disaster tourism allowing affluent westerners the illusion of empathy.

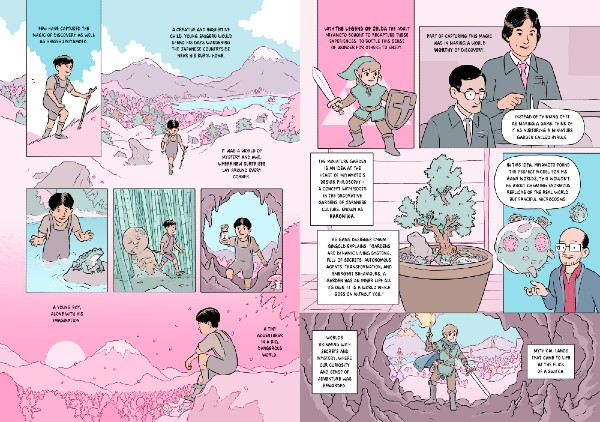

A section on the wonder of discovery begins with early text adventures before moving to the games of Shigeru Miyamoto and the birth of the Zelda franchise. With the lovely phrase “worlds of wonder that responded playfully to our presence there” he captures the inarguable beauty of Hyrule as depicted in the most recent Zelda game, Breath of the Wild. Quoting games writer Tristan Donovan, he notes that these enthralling games arrived just as societal changes meant children were less free than their predecessors as urbanisation changed the world their parents had grown up in, providing perfect conditions for gaming to thrive.

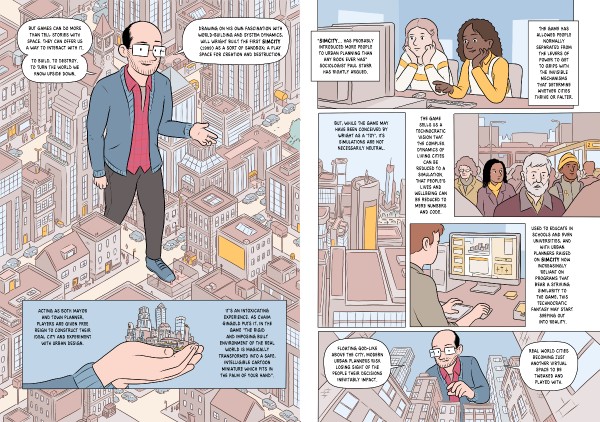

Ross’s stylistic trait of drawing himself into his images echoes the format of a TV documentary while serving to draw together the diverse settings he shows across numerous games. As he describes Sim City, he looms above buildings, larger than skyscrapers, then cups a city in his giant hands, before depicting himself viewed from street level as he speculates on the dehumanising impact the game has had on city planners and how they view the citizens that inhabit their real world creations.

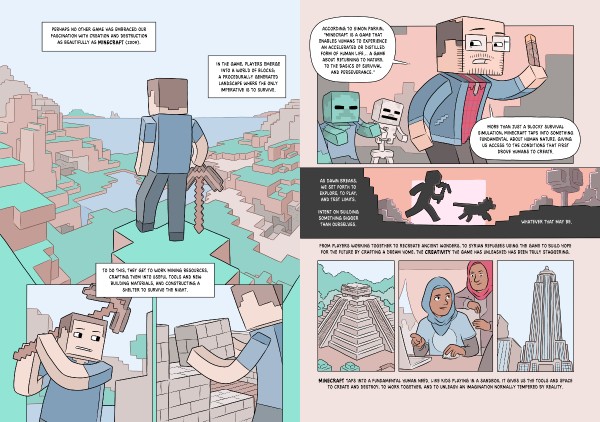

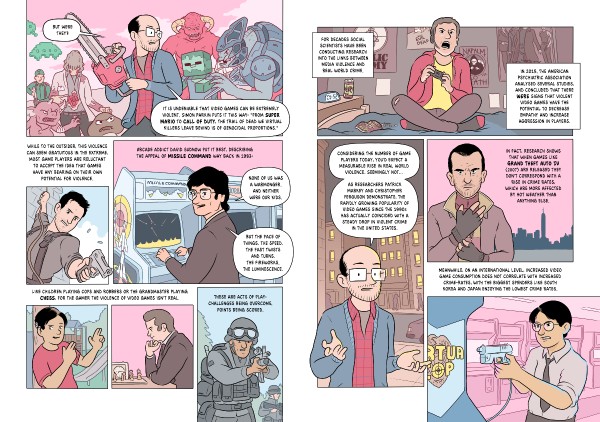

The book considers many games that have courted controversy, such as GTA V, but is never drawn into simplistic moral panics, instead presenting the game as a playground to foster fun and subversive interactions with city spaces. There is interesting coverage of games where the player is complicit in totalitarian regimes, like Papers Please, Bioshock and the creepingly horrific Spec Ops: The Line. Ross looks at the Columbine massacre and how the media tried to link it to Doom, before describing a moral panic about games dating from 500 BCE just in case we imagine such things are exclusively modern. Gaming addiction, the morally complex area of gold farming, and the deeply unpleasant toxic gamer culture that birthed Gamergate, the predecessor of Comicsgate are also objects of scrutiny.

In many ways this is an academic essay about play, what it means and the value it holds for humanity – the endnotes run for more than 30 pages. The fact that Ross has chosen the medium of comics to present this means that we get a degree of immersion into his ideas that mirror the immersion we can feel when playing games. This is an excellent book sure to appeal to video game fans of all ages. As Ross writes, “at their worst, games are capable of reinforcing expectations and stereotypes about race, gender, sexuality or disability. But at their best, games allow us to escape from those expectations, free ourselves from the limits of our own bodies and our own experience, and stretch out into an infinite array of possibilities.”. Gamish show us that world in an impressively engaging manner.

Edward Ross (W/A) • Particular Books, £20.00

Review by Pete Redrup