MYRIAD WEEK!

The winner of the very first Myriad First Graphic Novel Competition for his debut book The Black Project, Gareth Brookes is an artist whose reach straddles both the DIY culture and zine world and the comics and graphic novels arena. A prominent member of the Alternative Press in its early days and a frequent collaborator with Steven Tillotson (Banal Pig, Untitled Ape’s Epic Adventure), his often darkly humorous work is marked out by his constant experimentation with form, presentation and narrative.

Today, as part of our ongoing Myriad Week, I chat with Broken Frontier Award-winning Brookes (signing at last week’s Gosh! Comics below and above centre with Owen D. Pomery and BF’s own EdieOP at Small Press Day last year) about the importance of a healthy zine scene, finding the terrifying in the mundane, and his second graphic novel ‘A Thousand Coloured Castles’ published this week by Myriad…

ANDY OLIVER: Was your route into comics a traditional one? And what is it about the storytelling potential of the form that most appealed to you?

GARETH BROOKES: I’m not sure what the traditional route into comics is. When me and Steve (Tillotson, Untitled Ape’s Epic Adventure) started out there was pretty much nothing going on in the small press scene at all. People used to take portfolios of fan art around comic cons and try and get work with whatever mainstream comics company was there but I never heard of anyone actually getting work that way.

Me and Steve met at the RCA and just got sick of the art world’s boring, self-congratulatory futility. The fact that you could even tell stories in comics was refreshing to us. For the most part, storytelling is frowned upon in contemporary art. We just wanted to be disgusting and weird without having over-educated onlookers re-contextualise it from a deconstructivist perspective.

You’ve been something of a mainstay on the small press scene for many years now and were an important part of the Alternative Press in its early days. How has the self-publishing scene changed and evolved in that time?

Well it’s gone from a handful of outsiders making photocopied and badly stapled pamphlets about shitting yourself/robot ghosts being ninjas or something to an amazing scene full of frighteningly talented artists making stuff that’s completely indistinguishable from commercially published books. When I joined Alternative Press this is more or less the state of affairs we dreamed of.

The first International Alternative Press Fair

Having said that there is a risk of complacency. People have always said “the small press scene has never been healthier” even when it was an international embarrassment. I think there is so much opportunity for new artists to get their work into the world that they don’t have to make their own weird little fairs and anthologies like we did. And that’s not good because weird little fairs and anthologies are important for growing the audience and community.

Another negative difference is that I think small press comics have drifted away from the zine scene. When I was making my early work zines were probably more important to me than comics, and exposure to the politics, aesthetics and DIY ethos of zine-making had a huge effect on how I go about making work. There’s a danger of new artists thinking that small press is just practicing for being “properly” published. It isn’t. It’s an opportunity to be as contentious, inflammatory, disgusting, weird, ugly, stupid, serious, avant-garde, lo-fi etc., etc., as you like, and I worry that new comics artists are playing it a bit safe at a time when we should all be thinking a bit about what our role as artists might be in broader society.

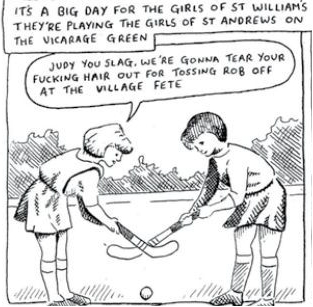

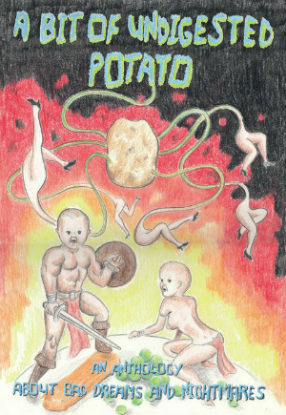

Gareth’s cover to Keara Stewart’s A Bit of Undigested Potato and a page from his Broken Frontier Small Press Yearbook story

You’ve always had a notable presence in anthology collections – The Comix Reader, A Bit of Undigested Potato, Tiny Pencil, Kuš’s š! anthology, and even our own Broken Frontier Small Press Yearbook all spring to mind. How vital is it for self-publishers to get involved with anthologies in terms of profile, making contacts and interacting with the scene?

It’s great for connecting with other artists. The Comix Reader in particular felt like a bit of a gang. Having something regular to contribute to was important for all those artists I think. With something like kuš! it was great to be involved with something so international. I think we all know that as a nation we’re a bit too island-minded, and that’s no good if you’re a comics creator.

But I think the most important part about anthologies for me is that they help you develop new work. Half the comics I’ve made have started out from having the opportunity to experiment a bit in various anthologies. It’s more important to me than ever because when you’re half way through a graphic novel that’s taken you years and years, it’s refreshing to be able to step away and focus on something else.

From Can I Borrow Your Toilet? (above) to The Smell of the Wild your earlier zine output was certainly eclectic in subject matter and medium. Can you give us a brief rundown of the themes and subject matter of some of that work?

Can I Borrow Your Toilet? was influenced by autobio zines, and by my being quite impressed by the van drivers I was working with at the time, as their philosophical outlooks seemed more considered and resolved than those of the university professors I had been used to. I wanted to examine the mechanics of a masculine environment in all its emotional complexity. I think this fed into The Black Project, which I thought about at the start at least as a satire about heterosexual masculinity.

The Smell of the Wild was a bit of a piss-take of Diary of an Edwardian Lady. It was a kind of self-important twee and talentless poet character who thinks he can describe nature in a picturesque and exaggeratedly ‘nice’ way.

Similarly your earlier collaborations with Steve Tillotson are fondly regarded and were even revisited a couple of years back when Avery Hill published The Manly Boys & Comely Girls Annuals (above and below right). How did that creative partnership come about and why do you think your approaches to humour so richly complemented each other?

It was all Steve’s idea to do comics. I was all for ploughing on with trying to put on art exhibitions, but he was determined to create Banal Pig #1 and for some reason it was unthinkable that I shouldn’t be involved in some way. The division of labour in those days was 97% him 3% me. When we started tabling together at fairs, and I started making my man man comics we really began to collaborate properly.

It’s hard to say why we work together so well. We both have a pretty dark sense of humour. In some of those early Banal Pigs it felt like we were trying to out-dark each other a lot, especially on stuff like Jolly Bear Summer Special. Some of that stuff went a bit too far! No one found it funny, including us!

It’s hard to say why we work together so well. We both have a pretty dark sense of humour. In some of those early Banal Pigs it felt like we were trying to out-dark each other a lot, especially on stuff like Jolly Bear Summer Special. Some of that stuff went a bit too far! No one found it funny, including us!

I think the Manly Boys & Comely Girls Annuals worked well because we had a target for our caustic satirical barbs. We were trying to make a point about how children get ascribed gender roles and how nationalism plays a role in that, and that made us focus our dark humour a bit.

How important was the Myriad First Graphic Novel Competition to you in providing the next step up in recognition? Was it a surprise to you when you won for The Black Project in 2012?

Hugely important. It came at a time when I could very easily have given up comics. I’d spent such a lot of time organising events with the Alternative Press that I’d produced very little and was feeling a bit lost. The Myriad prize was a real kick up the bum at just the right moment, and it came as a huge surprise.

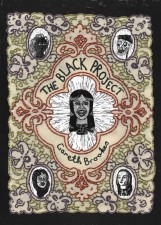

I was amazed to be shortlisted because I was aware that the book was so weird both in content and execution. It’s a matter of some contention about whether it’s a comic at all. So to be recognised in such a way, and have Myriad take such a risk on such an idiosyncratic project was humbling.

“Clandestine first love with a papier mache twist is the order of the day in this remarkable debut graphic novel” was the way I described The Black Project when I reviewed it here at Broken Frontier . What’s the basic premise of the book?

It’s about a young boy who’s a bit of a misfit and doesn’t have many friends who makes himself some girlfriends out of things he finds lying around the house. He then has romantic moments and tentative sexual encounters with them.

One question I’ve asked every interviewee in this series of Myriad interviews is how did you find the experience of working with an editor for the first time? Did The Black Project evolve in different ways because of that input?

I wasn’t sure what to expect at first, and it was difficult because for the first six months of my professional relationship with Corinne (editor at Myriad) I was in New Zealand. However I’ve found Corinne extremely easy to work with. She seems to have a great deal of faith in me which encourages me to have faith in myself, and she gives me a lot of space and time to develop the work. She has a subtle way of prodding me along the right path and I’ve learned a great deal about how to pace a book so that it sustains the reader’s interest over two hundred or more pages.

I think The Black Project moved towards a slightly more traditional comics format under Corinne’s guidance because I understood the need for the reader to connect with the characters and that giving them sequential passages was the best way to do that. On a basic level it’s invaluable to have someone to tell you when what you’ve done doesn’t make any sense. Things are always very clear to oneself, but even the best and most experienced comic creators do things that can be horribly misread.

From the embroidery and linocut of The Black Project to the unique crayoned presentation of your latest graphic novel A Thousand Coloured Castles you’re renowned for pushing comics in different directions in terms of presentation. Even the physical format of your self-published books is constantly shifting – your “handmade wordless, psychedelic, semi-pornographic, mono-printed sci-fi epic” The Land of My Heart Chokes on Its Abundance (above) springs to mind. How important to you is a constant sense of experimentation in your work?

It’s important because otherwise I would become very bored. I think one of the things I took from all those years at art school was that the form of a thing and the materials you use are important and bring with them a lot of the message you’re hoping to convey. I like to struggle with materials and not quite know what I’m doing and be always on the point of failure. This is the time that creative things can happen in the work, and I hope that brings a tension to the work that a reader can pick up on.

It’s also important that I’m enjoying what I’m doing since I have to do the same thing over and over every day for years. The idea of my being a professional, who goes to his desk every day and picks up the same materials, and draws the same sort of thing and knows what he’s doing and has mastered his craft, is an idea I find suspect on every level and also physically sickening.

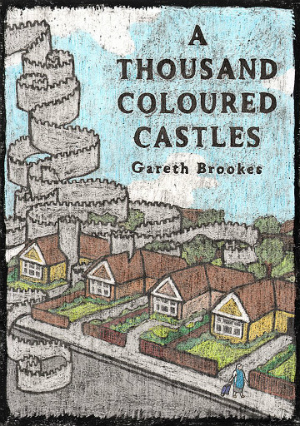

Your new graphic novel A Thousand Coloured Castles launches from Myriad this week. Tell us a little about its subject matter and your creative process on the book?

Your new graphic novel A Thousand Coloured Castles launches from Myriad this week. Tell us a little about its subject matter and your creative process on the book?

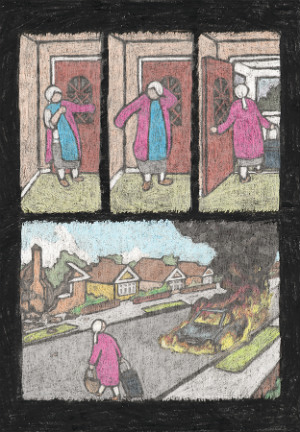

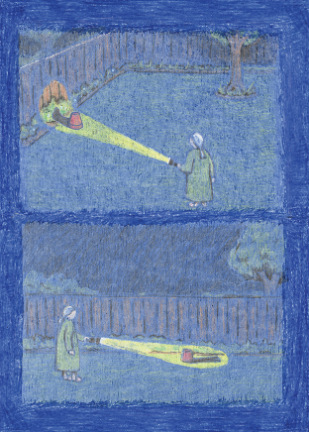

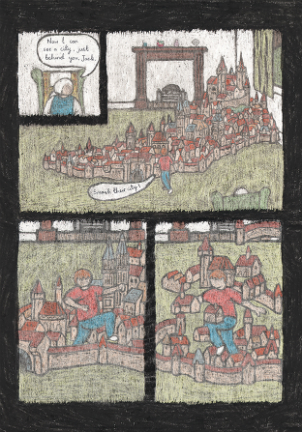

There’s a lot of different themes going on in the book. Essentially it’s about an elderly lady called Myriam going against her husband in order to get to the bottom of the mysterious goings-on next door. At the same time she is losing her sight and beginning to suffer from a condition which causes hallucinations, so what we see is all mixed up, and the ordinary everyday weirdness of suburbia is indistinguishable from the bizarre visions her condition is causing.

In terms of the creative process it was very different from The Black Project. With that book I had the text before I started working on the images, but with this book the images came first, it was like I was illustrating a very vague almost dream-like narrative that was somewhere inside my head. The dialogue was added later and often the tone of the images or the attitudes the characters seemed to be taking suggested what the dialogue should be. This way of working was troublesome in that I didn’t know quite what was going to happen throughout most of the drawing of it, or how long the book was going to be. In addition there were a huge amount of continuity errors that I had to deal with at the end, that I could have avoided by just working it all out a bit at the start.

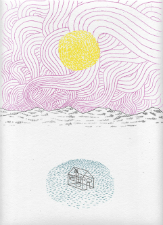

The artwork is all done with wax crayons. I remembered being quite little and on Bonfire Night they used to make you do these crayon drawings at school where you would cover the page in a rainbow of colours, then go over it all in black, then you’d get a pin and scrape away the black revealing the colour underneath. I wondered if it would work for a whole page of images, so I started doing a few experiments (see video below).

It’s a very strange process, it makes the colour oddly lurid at times and washed-out at other times. There’s something very dream-like about it, and the whole thing seemed appropriately analogous to the loss of vision the central character is experiencing. Lots of people ask me why the colour underneath doesn’t scrape away as well, I have no idea, there must be a scientific explanation I suppose. Working in this media meant that to get the level of detail I wanted I had to work quite large. Most of the pages in A Thousand Coloured Castles are composed of two A3 sheets.

Can you give us some insights into the research that went into A Thousand Coloured Castles and what it was about the subject matter that so intrigued you?

I did a great deal of research into Charles Bonnet Syndrome (which is the condition the protagonist suffers from). My Grandma had it and I used some of the hallucinations she experienced in the book. I met several times with a specialist called Dr Dominic ffytche from Kings College Hospital and that ended up being really important. It gave me a feel for this uncanny and disturbing condition. With CBS you have to learn to recognise what’s real from what’s not by becoming familiar with your own brand of hallucination.

It’s as fascinating from a literary standpoint as it is from a medical one because of the things it allows you to do with narrative. Myriam is like an unreliable narrator, only that unreliability is visual, so I was exploring what happens when a person comes up against their subjectivity. It’s an idea that lends itself to comics very well because everything in comics comes out of the human brain via the human hand.

In all the other storytelling mediums there are props borrowed from external objective reality, like locations in a film for example or in novels the typography has the authority of being objective somehow. But in comics every aspect can be manipulated, so everything can be made disorientating and untrustworthy, and something about that is very exciting to me because it feels like the world we’re living in now.

As a reader, if there’s one throughline I see in your work it’s a sense of a darker undercurrent that manifests itself in the everyday and the mundane. Is that something you explore by design or is it a symptom of an overactively misanthropic subconscious?

I’m not really a misanthrope. It’s true that I despise all humanity, but people as individuals are always beautiful to a degree. Their lives and stories and secret passions are endlessly fascinating and life-affirming. Eavesdropping on a particularly human conversation can render me impossibly happy for a day at least.

I think it’s the idea that the dark things are pushed below the surface of the everyday and mundane and that the ‘normal’ thing to do is to hide things from ourselves that I find truly frightening. That everything shadowy is concealed by a veneer of niceness and acceptability, it’s this veneer that is the true horror.

And, finally, are there are any other comics-related projects you’re embarking on in the near future? Or will you be having a well-deserved rest now that A Thousand Coloured Castles is out in the world?

Of course there are! But I’m saying nothing. I’ve learned that jumping into another graphic novel straight away would be ruinous, and that talking about a project before they’ve got going is a sure way of killing it. I’m looking forward to submitting some anthology stuff and a small press comic or two is definitely on the cards for the next twelve months.

For more on the work of Gareth Brookes visit his website here and follow him on Twitter here. You can visit his online store here.

Buy A Thousand Coloured Castles online here and The Black Project online here.

[…] Interview: “It’s True that I Despise All Humanity but People as Individuals are Always Beautiful to a Degre… via @BrokenFrontier […]