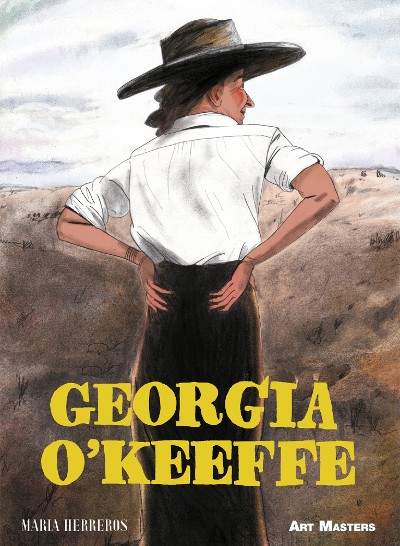

The newest edition to SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series, Georgia O’Keeffe is a graphic biography written and illustrated by Maria Herreros and translated from the Spanish edition from Astiberri Ediciones.

The book is structurally straightforward in its recounting of the artist’s life, but explores the key themes sparsely and sensitively throughout, making for a very readable and evocative journey through the key moments of O’Keeffe’s career and the development of her practice.

Herreros spoke at LDComics online monthly meet-up in May, and talked about her beginnings in small press and the passion and creative freedom that she found there (check it out on the LDComics Hub on YouTube here ). She has walked the knife edge of looseness and purpose to keep the energy of her early zines alive in her extensive career as an illustrator and graphic novelist. This emphasis on channelling a spirit of freedom and ‘zero expectation’ in her work speaks to what makes her a good match for O’Keeffe. Both are embodiments of the maxim to follow your heart and make the work that speaks to you, as this is what will really reach people.

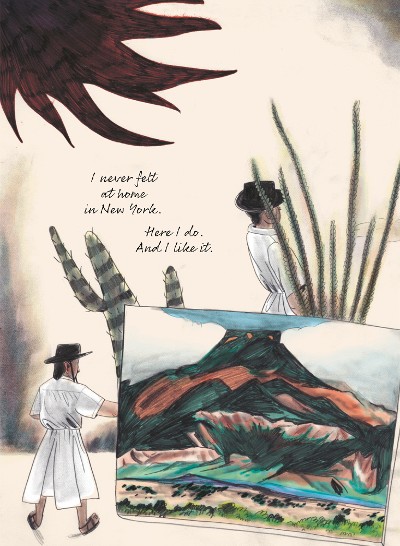

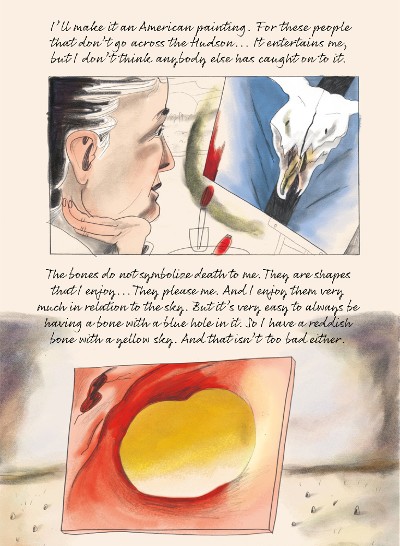

Georgia O’Keeffe is most famously known for her giant close-up semi-abstract paintings of flowers and animal skulls. She succeeded in making a good living as an artist in an American art scene dominated by men and is one of the few female artists to break into what might be considered the Western Art Canon – and the first to feature in SelfMadeHero’s line-up. Her work is sometimes reduced to a joke about flowers looking like sex organs or merely feminine expressions of beauty, an angle that her husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz was happy to exploit to sell her work. But O’Keeffe’s work was about so much more than this, and her life is an inspirational tale of what can be achieved by an artist who has the courage to really pursue their individual vision. An American attitude indeed, and the Americana of O’Keeffe’s image is never stronger than in the latter part of her career where she lived alone in the desert of New Mexico. Herreros encloses the second half of the book in this soft, layered scenery and the desert becomes another character in the book.

(Really there’s hardly any pictures of flowers in the book at all. Just to set expectations. This is very much not a book about flower paintings. If you want that, get a book of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings.)

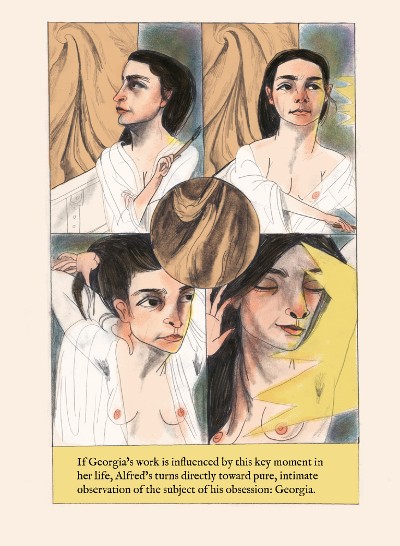

Making this book during the pandemic, which is so much about finding freedom, Herreros didn’t only explore this transformation through location, but also bodily autonomy. There is a particularly clever mirroring of two spreads from 1918 and 1934, the first a montage of Stieglitz’s nude photographs of Georgia, and the second a montage of the artist dressing herself as she returns to New Mexico after being hospitalised for ‘psychoneurosis’. Here O’Keeffe is shown to be taking control of her own life and her own image, still attached to but satellite from her husband and his artist’s circle. The difficulty that a woman has in existing in a world that defaults to seeing her firstly as a body – a vessel for men’s imagination, seed and children, washes away under O’Keeffe’s stern refusal to be anything but herself.

Using charcoal and mechanical pencils with soft digital colour, Herreros’ characteristic style includes widely spaced features, almond eyes and long, rebellious noses. She dances always between realism and distortion, beauty and ugliness in her work while never conceding much to convention, creating a compellingly subtle tension. The sketchiness is not particularly reminiscent of O’Keefe’s work, but her love and respect for the American artist suffuses the pages unapologetically. Through colour, and a playful range of approaches to panel shape and form, she evokes a sensitive, sensuous experience of life that does chime with the painter’s outlook. It reminds me of the work of Isabel Greenberg crossed with Ellie Cryer.

Maria Herreros (W/A), • SelfMadeHero, £14.99

Review by Jenny Robins