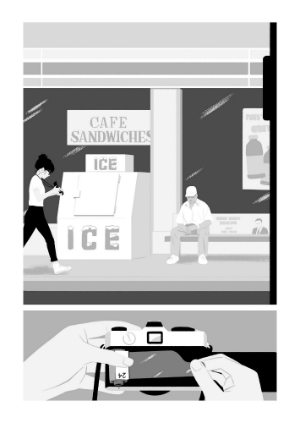

For a hot minute at the turn of the millennium, the hot trend in superhero comics was for “widescreen” page layouts. That is, panels that took up the breadth of a page so as to allow room for the artist to cram in as much blockbuster action as possible. More bang for the reader’s buck. In GG’s I’m Not Here, from Canada’s Koyama Press, the same technique is used for a very different reason: the wide open negative space of the panels, rendered in grayscale and largely without linework, serve to highlight the isolation of the book’s central character.

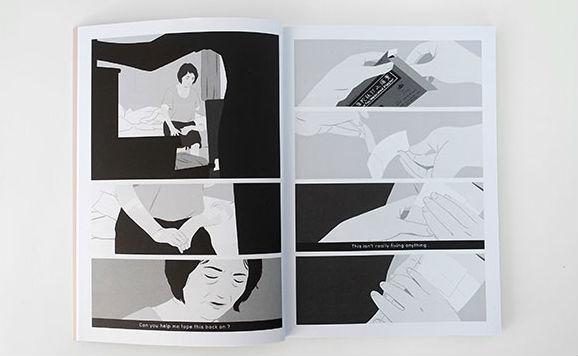

Looking after her ailing parents — a father who can’t remember his way home and a mother for whom she’s become the de facto live-in carer — the unnamed, second generation protagonist of I’m Not Here lives an otherwise solitary, quiet life, free of other people or incident. Room in panels that would otherwise be given over to word balloons or action remain empty or static. When there is dialogue, it appears in a black bar along the bottom of panels, like a caption, or subtitles.

Looking after her ailing parents — a father who can’t remember his way home and a mother for whom she’s become the de facto live-in carer — the unnamed, second generation protagonist of I’m Not Here lives an otherwise solitary, quiet life, free of other people or incident. Room in panels that would otherwise be given over to word balloons or action remain empty or static. When there is dialogue, it appears in a black bar along the bottom of panels, like a caption, or subtitles.

A market stall owner asserts the opposite. When snapping shots of his wares, she admits her photography hobby is mostly to “have a record of how thing are,” which he insists must keep her busy. After all, he says, “the way things are is that they’re always changing!” But that’s not this character’s experience. The opening pages go almost frame-by-frame, like animation stills, through what we assume to be a daily routine. Get up, tie her hair back. Stare at the ceiling. Look after her mum. Cook, wash up. Sit alone in her room and read.

After the soft peach background of the cover, the rest of the book is all whites, greys and the occasional heavy black (for the eyes and hair of the characters, buildings in the dead of night, the darkness around the sights she captures in her camera’s lens), fading away further during flashbacks. An absence of colour is often said to signify an absence of feeling, and a book the main character reads suggests that “feeling is impossible if we feel today as we did yesterday; to feel today the same thing we felt yesterday is not to feel at all…”

Trapped in routine, is she consigned to a life without feeling? Her amateur photography offers a glimpse at an alternative life, one free of obligation or responsibility. Through her viewfinder she glimpses a beautiful young woman. Upon developing the picture, she discovers the woman looks not unlike her as she imitates the coy over-the-shoulder look in the mirror behind her. Returning to the apartment building she saw the woman outside of, the elderly landlord mistakes our protagonist for her subject, and lets her in.

While absent of people, the rooms shown in these panels are cluttered with evidence of a life lived, in deliberate contrast to her home: a passport full of stamps atop a boarding pass, photographs of past trips, a wardrobe of different outfits distinct to her uniform of a white shirt and black trousers, an active answering machine (which, upon the character’s arrival, takes a call from the woman’s mother, who apparently hasn’t seen for a while; by point of comparison, she was dutifully applying bandages to her own mother just the night previous).

The uneasy development of a child into the caregiver for their parent, the normal roles reversed, is made starker through flashbacks to the character’s childhood. At one point she remembers her mother cleaning up after a mess made by her and her sister, and weeping. “I shouldn’t have come to this country. I gave up my old life. But I had to. For you.” It’s a slightly unbelievable line, but it neatly encapsulates the character’s internal conflict, why the hint of a different path might appear so seductive and yet she cannot quite bring herself to take it.

GG’s book is quiet, sad and often still, but not devoid of hope. The snatches of easy intimacy between the character and those she meets sometimes literally brighten things. Her clear illustrative style mostly serves to show the isolation of the character — alone on her bed and situated in the bottom corner of the panel, dwarfed by the emptiness of her sparsely-decorated room — there are moments of indelible imagery, like the silhouetted suburban roofs and treetops like a cut-out against the grey-green night sky. Beneath a meditative, lonely story lies a complicated reckoning with independence and familial responsibility, for which there are no easy answers.

GG (W/A) • Koyama Press, $12.00

Review by Tom Baker