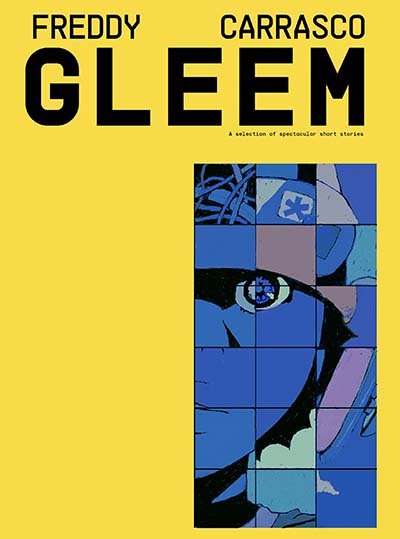

It has been four years since Dominican-born artist Freddy Carrasco took home the Ignatz Award for Outstanding Collection, as well as the Doug Wright Award for Best Small- or Micro-press Book, both for a collection of short stories. GLEEM, back on bookshelves thanks to the perceptive folk at Drawn & Quarterly, serves as a reminder of what made Carrasco’s work innovative at the time, and why it is more relevant than ever.

When it comes to graphic fiction, experimentation sometimes gets a bit of the side-eye, which is undeserved when one acknowledges that great artists don’t create something because they need the validation of an audience. Carrasco’s stories are anything but predictable, but they come from a place of quiet confidence. It explains the compliment from Canadian artist Michael DeForge—no stranger to the avant-garde himself—on the back cover, professing love for a comic “that trusts you’ll be able to keep up with it.” He’s not wrong.

GLEEM exists in a world of Afrofuturism, defined by scholar and writer Ytasha L. Womack as ‘a way of looking at the future or alternate realities, but through a Black cultural lens.’ Its three stories (‘Born Again’, ‘Swing’, ‘Hard Body’) take off in what appear to be different directions at first but, gradually, reveal a shared exploration of isolation. It feels like a Jimi Hendrix album in comic form, its characters stuck in a present that is anything but ideal, but with hope for a brighter future.

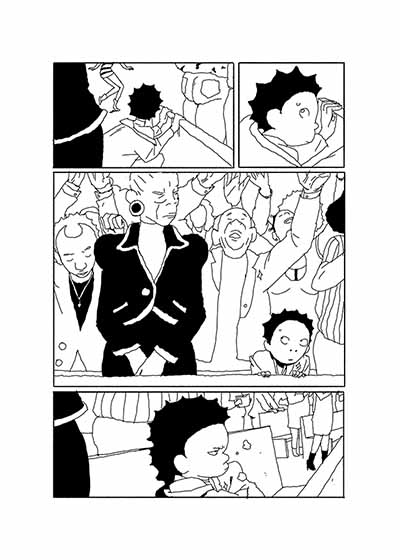

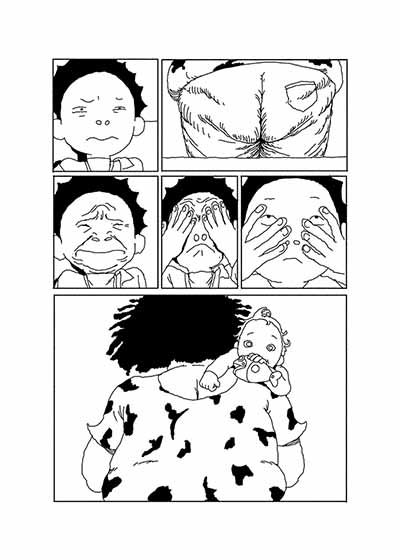

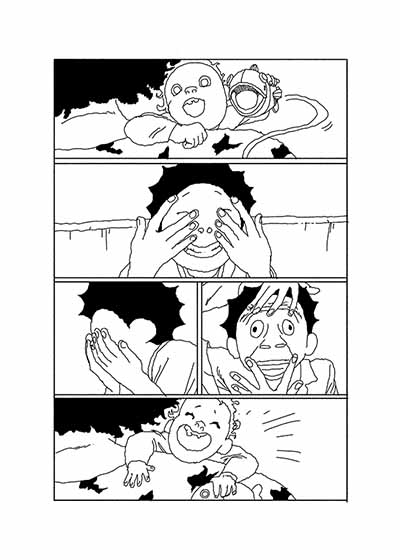

Carrasco’s work has sometimes attracted comparisons with mangaka Taiyo Matsumoto, not because the latter also has a proclivity for post-apocalyptic wastelands, but because of how recognisable it is to anyone who has read Tekkonkinkreet. Also, like Matsumoto, he has a knack of creating characters that aren’t etched in great detail but offer enough to compel a reader to find some measure of engagement.

An interesting aspect of this fictional universe is how it underscores claims that have long been made about marginalised communities and the digital divide that gives them unequal access to technology. In this context, people of colour often occupy a space that is somewhat opposite to technological progress, making these stories quietly subversive. The first one, ‘Born Again’, delves into the hypnotic and dubious attraction of organised religion. ‘Swing’ is darker, but almost prescient in its depiction of a world where the lines between human and artificial intelligence are increasingly blurred. ‘Hard Body’ allows Carrasco to rely solely upon his art to drive the narrative (such as it is) forward and is arguably the boldest story.

One of the more striking things about these stories is how much optimism there is, despite a constant sense of disquiet and the relentless boredom exhibited by their young protagonists. They move in worlds that are both born of as well as radically removed from our own, but their lives aren’t devoid of courage. On the contrary, they exhibit a version of humanity that is increasingly being propped up by people who believe it is the youth who will save us. They may or may not, but they definitely have their eyes set on something better.

Carrasco’s work encourages a reader to ‘expand the outer layers of possibility.’ It’s not easy, but it never ceases to be exciting either.

Freddy Carrasco (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $22.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira