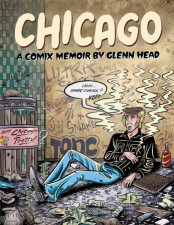

Staggeringly personal, Glenn Head’s Chicago (Fantagraphics Books) is a storytelling triumph. Its creator joined us to talk about his creative process and approach to making comix.

Underground comix are alive and well, which comes as absolutely no surprise when you open the pages of Chicago, the latest effort from artist Glenn Head and Fantagraphics.

The memoir is a masterclass in the modern underground, as Head’s definitive artistic style showcases his influences, including Art Spiegelman, Robert Crumb, Chester Gould, Hieronymus Bosch, and Charles Schultz, among many others. (Glenn Head’s website contains a full list of his influences from the worlds of visual art, photography, writing, filmmaking, and music. It’s a fascinating compilation and sure to contain some artists you need to check out immediately.)

The memoir is a masterclass in the modern underground, as Head’s definitive artistic style showcases his influences, including Art Spiegelman, Robert Crumb, Chester Gould, Hieronymus Bosch, and Charles Schultz, among many others. (Glenn Head’s website contains a full list of his influences from the worlds of visual art, photography, writing, filmmaking, and music. It’s a fascinating compilation and sure to contain some artists you need to check out immediately.)

Head’s line work and attention to the smallest of details give every panel a life of its own; you’ll have to read it more than once to catch everything. As with other underground comix, the backgrounds are just as important as the action taking place in the foreground, so pay attention! One of my favorite details is the R. Crumb poster on Glen’s bedroom wall that moves and appears in various states of distress as his situation heads downhill.

Chicago is an intimate voyage of personal discovery along the jagged edge between reason and madness that so often defines major turning points and permeates our daily struggle with life, death, and meaning. Themes of life and death are ever-present, and Head treats both as constant companions rather than cyclical themes.

Without giving too much of the story away, the book begins and ends in a graveyard. Whereas that might simply be considered a place of ending and finality, for Glen – the version of the author on the page – it’s an affirmation of life and a source of inspiration.

Without giving too much of the story away, the book begins and ends in a graveyard. Whereas that might simply be considered a place of ending and finality, for Glen – the version of the author on the page – it’s an affirmation of life and a source of inspiration.

The building blocks of character are often forged from moments of questionable spontaneity. In the book, young Glen is in for the education of his life when he suddenly drops out of art school and heads for Chicago. The Windy City is a rough place for a kid on the brink of madness with no money, no job, and nowhere to spend the night.

Rather than attend art college (as his parents think he’s safely doing), Glen learns to panhandle on street corners for food money, resist a constant barrage of sexual predators, and accept genuine help from others barely able to help themselves. And when he receives his first commission from Playboy magazine, he learns the value of persistence.

As an autobiographical work, Chicago resonates with the kind brutal honesty that can only be achieved by an artist who isn’t holding back the bits that don’t make him look good. Let’s face it, throughout the story Glen makes some really bad decisions – taunting Muhammad Ali, for example – and it’s refreshing to read the scenes as they played out absent any sugar-coating. Love, life, sex, race, death, identity, depression, and family are all addressed with an unapologetic openness.

I thoroughly enjoyed Chicago. Honest, poignant, and fierce, it’s everything a good autobiography should be, and I was thrilled that Head agreed to share his experiences in creating the book. But I had a problem: he did a very nice interview with Tom Spurgeon (The Comics Reporter) about the inspirations behind Chicago and the story itself.

I thoroughly enjoyed Chicago. Honest, poignant, and fierce, it’s everything a good autobiography should be, and I was thrilled that Head agreed to share his experiences in creating the book. But I had a problem: he did a very nice interview with Tom Spurgeon (The Comics Reporter) about the inspirations behind Chicago and the story itself.

So rather than discuss the narrative elements, I went in a different direction with our interview and focused on his creative process and approach to making comix. Head’s thoughtful responses are every bit as revealing as the story he tells in the book.

First, I asked him to discuss the script process, laying out the panel placements, and the importance of flexibility as he moved from script to the drawing phase.

“The script process, for me it’s very involving. I see almost no point in drawing unless I have the story and script nailed down. The main issue overall – I have to know where it’s going. In writing out the story of Chicago, the one part of the book, the easiest one to do script-wise was the Chicago chapter, although I still had to write several drafts before I had what I wanted. So the first part of the book I actually drew was the third chapter – then I had to loop back around to the beginning. This all worked out because the beginning of the story presented itself – me in a graveyard – and there I was.

I feel the chance to draw has to be earned – earned by a good story.

“But for me the drawing, which I take very seriously and really work hard at, I feel the chance to draw has to be earned – earned by a good story. I read some interview with a cinematographer who said that no amount of good filmmaking can save a bad story, and no amount of bad filmmaking can wreck a good one. I like that statement, because whether or not it’s true, it says the story is the skeleton, the structure, the essence. Everything else, no matter what it is – beautiful or mediocre – it’s just window dressing.

“For me the writing and rewriting of drafts is done to get to the heart of the matter. It can help for the pacing of a story, but really it’s about boiling it down, trying to get closer to the story’s essence. It seems to me that I may actually write close to ten drafts of the story for something like Chicago. These drafts are usually written out and drawn in a kind of very rudimentary breakdown form. About eight or nine panels per page. The drawing is no more fleshed out than it needs to be so I can see what’s going on.

“Sometimes in the process of doing that I’ll come upon something and think, This one, it has to be a full-size drawing because it could be powerful – all the details that go into it could really mean something. This brings the narrative to a momentary standstill, but it can be worth it for the impact. Basically though, I’m flexible with a script in terms of what it’s going to mean in terms of panels on the page, etc. In fact I’m really deciding that as I go on with the actual drawing – penciling – of the comic.

“Sometimes in the process of doing that I’ll come upon something and think, This one, it has to be a full-size drawing because it could be powerful – all the details that go into it could really mean something. This brings the narrative to a momentary standstill, but it can be worth it for the impact. Basically though, I’m flexible with a script in terms of what it’s going to mean in terms of panels on the page, etc. In fact I’m really deciding that as I go on with the actual drawing – penciling – of the comic.

“Drawing comics is obviously heavy-duty labor. The big struggle, besides the struggle itself: how can I keep this interesting, fun even, as I go on with it? If I had plotted out in advance where everything was going, like which panel where, etc, it wouldn’t allow for any experimentation at all in the process. I need that, that option to change things, move them around when I’m at the final stages. Otherwise I’m bored.

“I think I’ve worked this way for some time now. The whole idea of working in a breakdown format was something I learned in Art Spiegelman’s class at SVA [School of Visual Arts]. It was really a revelation to be taught how Harvey Kurtzman worked, wrote out the comics he did for MAD, and then to see how the greats – Wood, Elder, Davis, etc – ran with it.

“In fact what I see here that’s interesting… my favorite of Kurtzman’s artists was Elder, and all of the insane, hilarious, “chicken-fat” that Elder put in was not pre-scripted by Kurtzman. There’s a freshness about that work. It’s really just wacky shit that Elder improvised in the moment! A good example for making stuff up along the way, letting it happen.”

A great many of my influences are 1960s comix artists. In drawing Chicago I wanted that same level of lived-in fucked-upness.

Next, I asked Head to discuss the materials he uses to create comics and how the physical process of creating pages affects the outcome of his work.

“My process is just completely old school! It’s all just pencil and ink – that’s it! In fact I was very conscious of wanting Chicago to be ‘underground’ in its feel. A great many of my influences are 1960s comix artists. What I loved about a lot of that work was its tactile grunginess. I saw a lot of that work, and it was transporting to me. Just by the look of it I could see the artists lived in a different world. I grew up in the suburbs of New Jersey, an environment that prized ‘normalcy’.

“The level of detail in the work of 1960s undergrounds gave nearly all the work a kind of homemade quality. The art was somehow ‘lived-in’ or something, like something the artists wore – like an old work shirt with cigarette burns in it.

“In drawing Chicago – a lot of which takes place in grungy areas, men’s shelters, street corners, south side ghettos – I wanted that same level of lived-in fucked-upness. And I felt that would be more present if I drew every detail, every garbage can, every rusty beer can, as I remembered experiencing them. And that obviously meant taking time with the details. All the shading, the dots, the crosshatching… it’s by hand.

“Still, I watch it. If you spend any time looking at my work, you’ll see that I take the graphics very seriously. My comics read. You can’t be confused reading Chicago. Everything follows as fluidly as I can make it. But those details – I gotta have ’em!

“I use a Winsor Newton 00 brush for a good chunk of my ink-work, as much as possible. I love the brush because the line is organic, imperfect, never fully controllable. All my outline work including dialogue and thought balloons, panel borders – that’s all brush – I love it!

“I use Rotring rapidographs for certain hard-to-nail details—hands, fingers, eyes, and obviously for lettering. For cross-hatching too – I might use a zero or double-zero if I want the lines really small. Occasionally a #2 rapido for some outlines. Not too much.

“I have no interest in computers in drawing comics. None. But I’m not above the occasional tweak. The area where I really went to town on that is with my lettering… moving words around in dialogue balloons… making certain letters smaller. If I was gonna admit to a weakness in my craft as a comic book artist, I’d admit to that: my lettering—not great!

The memoir, especially if it’s about the trauma in a person’s life, may not be usable as material until the author has enough distance.

And finally, I asked him to share some advice. Writing elements of autobiography into comics is deeply personal. What advice does he have for creators who want to tackle an autobiographical project?

And finally, I asked him to share some advice. Writing elements of autobiography into comics is deeply personal. What advice does he have for creators who want to tackle an autobiographical project?

“It all depends on what kind of autobiographical project! For me, my memoir is deeply personal, I put a lot out there regarding issues of sex, race, family wealth, art, madness… In actual fact I don’t know if one can ever be ready to work with certain subject matter – but one can be not ready enough.

“I think I always knew I was going to work with the material that made up Chicago, but it was going to be a while before I could face it. So that’s one thing I’d say. The memoir, especially if it’s about the trauma in a person’s life, may not be usable as material until the author has enough distance to use it as material.

“Years back I did a three-page strip called The Muhammad Ali Story! That was really just a tiny piece of the Chicago story. It was pretty well received, and it opened something up for me – I started thinking about doing something long-form. Arguably, doing that strip planted the seed. The obvious point here is that working with autobiographical stuff in shorter form can get you revved up for a big project. If it feels right.

You gotta feel like your story is a big deal, something mythical almost, to portray it in comics form.

“But you have to be ready. While I wouldn’t advise doing a self-exposing memoir to someone who’s a very private person. (No worries, they’d never do it anyway!) You gotta feel like your story is a big deal, something mythical almost, to portray it in comics form… In a way it’s just so grandiose! That’s okay…artists are grandiose anyway.

“Here’s one thing I always come back to: the artists who have really exposed themselves, made themselves vulnerable, they never, ever, come out the worse for it – your sympathy goes out to them. You feel for it all, what they’ve been through. That’s what I think. The shit I hate is the macho-self-aggrandizement, look-how-tough-I-am shit that some guys do in their memoirs. It’s just totally defensive, self-serving, and ultimately weak.

“If you’re gonna do a memoir don’t go easy on yourself. You’re asking people to read your book? About your life? Your history? You better have a story there, but please don’t try and make yourself look good! We’re all trying to do that, every day – in how we talk, look dress, everything. It’s boring!

“If you’re gonna do a memoir don’t go easy on yourself. You’re asking people to read your book? About your life? Your history? You better have a story there, but please don’t try and make yourself look good! We’re all trying to do that, every day – in how we talk, look dress, everything. It’s boring!

“The mask has to come off. Don’t be self-serving, don’t go into the memoir to settle scores – why bother? Hit a pillow instead, call your shrink or something.

“One of the main points of the memoir is to come to grips with something. When we read one that’s good we’re fascinated by that struggle that deep down we all face with love, loss, mortality. If the artist is making a genuine attempt to grapple with this, it’ll make interesting work regardless of skill – it’ll push through somehow.”

Glenn Head (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books, $24.95