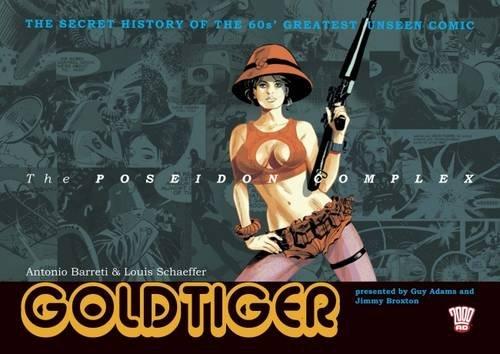

A chance encounter at the Malta Comic Con led artist Jimmy Broxton to the lost newspaper adventure strip Goldtiger – a classic document of 1960s comics. But that was only the start of the story…

It seems sometimes that in an often collaborative medium such as comics, a lot of the most interesting things occur on a spectrum ranging from happenstance to coincidence. And so it was with the rediscovery of the obscure newspaper adventure strip Goldtiger, rescued and presented here in “the secret history of the 60s’ greatest unseen comic”.

It seems sometimes that in an often collaborative medium such as comics, a lot of the most interesting things occur on a spectrum ranging from happenstance to coincidence. And so it was with the rediscovery of the obscure newspaper adventure strip Goldtiger, rescued and presented here in “the secret history of the 60s’ greatest unseen comic”.

The story starts at the fag-end of that decade, when the Baskervile Newspaper Group decided it needed to respond to the success of Peter O’Donnell and Jim Holdaway’s strip Modesty Blaise. To do this, it teamed up volatile Italian artist Antonio Barreti with English writer Louis Schaeffer – a multi-pseudonymous veteran of pulp and sci-fi magazines.

The strip’s protagonists were Lily Tiger and Jack Gold – two former mercenaries living undercover as fashion designers in Swinging London. Their debut story, ‘The Poseidon Complex’, started off conventionally enough, as the pair’s appetite for adventure leads then to investigate the disappearance of a number of boats on the Thames.

However, it didn’t take long for the, ahem, free-spirited Barreti to start pulling the work in a slightly eccentric direction. As former Baskerville art editor Brian McDuggan recalls: “As [Barreti’s] ‘reinterpretation’ of Schaeffer’s scripts began to filter through to the office, alarm bells began to ring.”

And if the innuendo-laden homosexuality of the leads wasn’t enough to get Baskerville executives hot under the collar, it soon became apparent that Barreti was beyond any kind of influence or control. The artist made plain his dissatisfaction with the conventional nature of the material, drawing himself into the story to pass ascerbic comment on what he was being asked to illustrate.

Barreti’s behaviour proved too much for his employers, and after being released from Baskerville, Goldtiger began an erratic publishing odyssey, from a left-wing German magazine, Ausflipper, to a Spanish newspaper that threw its own spanner in the works by printing the daily strips in reverse chronological order.

Strangely, it achieved its greatest success in Malta, which is where its journey back into the light started. While attending that island’s comic convention, artist Jimmy Broxton had one of those serendipitous encounters – a meeting with a man known only as ‘Marcello’ that left him in possession of the whole original artwork.

Following a bit of literary detective work by Broxton and his sometime collaborator Guy Adams, this book also presents a wealth of background material, including private correspondence, excerpts from Schaeffer’s (unpublished) autobiography, interview transcripts and extracts from commentaries and an introduction to a previous aborted collection.

It even reveals how – with the unlikely participation of Dave Gibbons – Barreti tried to push a futuristic revamp of the strip into the pages of 2000AD (right).

It even reveals how – with the unlikely participation of Dave Gibbons – Barreti tried to push a futuristic revamp of the strip into the pages of 2000AD (right).

Sadly, the publication of this book is the closest that the Goldtiger saga comes to a happy ending: Louis Schaeffer is thought to have drowned off the coast of Corsica in 1976, and Antonio Barreti disappeared without trace after leaving his last spell of psychiatric care.

However, in Broxton and Adams, the mismatched creators have two worthy literary executors. Bringing to mind Steve Aylett’s enlightening biography of author Jeff Lint, this is an entertaining – and often bleakly hilarious – insight into the shadowy corners of the creative psyche and a lost era of comics publishing.

More than anything, it serves as a reminder that the truth is nearly always stranger than fiction…

Louis Schaeffer (W), Antonio Barreti (A), presented by Guy Adams and Jimmy Broxton • Rebellion, £19.99

Great piece, Tom! What a fascinating story!

Unless I’m crazy (always a distinct possibility), that’s Broxton’s artwork 😉

Could this just be a fun hoax