Comics are by nature an intimate medium. The imagination required by the reader to fill the spaces both between and inside of panels fostering a deep connection between themselves and the characters on the page. It is this invisible bond that makes the first issue of Joey Perr’s Hands Up, Herbie! series stand out. Taking the form of several illustrated interviews with Perr’s elderly father (the titular Herb), the work becomes more than the sum of its parts by not only capturing Herb’s tumultuous life as young man in New York City, but also the atmosphere of a time which already feels disconnected from the present. The comic is specific in the details of Herb’s dysfunctional family drama while general in the milieu of late ’50s New York underclass Jewish culture. It is Perr’s work as a graphic documentarian that successfully communicates both experiences in a way that pulls the reader in.

Intercutting between shots of the present day Herb and his teenaged self we are introduced to the various members of his family, particularly his feckless gambler father. Almost an archetype of the absentee criminal father, Jerry has run up debts all over town and is frequently on the run from those looking for him to pay up. Herb frequently finds himself caught in the middle of this chaos and witness to his father’s attempts to con his family members or outbursts of violence at perceived threats. Herb also recounts how his father’s inability to provide turned into privation for him and his siblings and deep depression for his mother. While the relationship between Herb and his father is central to the comic it is part of a larger theme at work throughout.

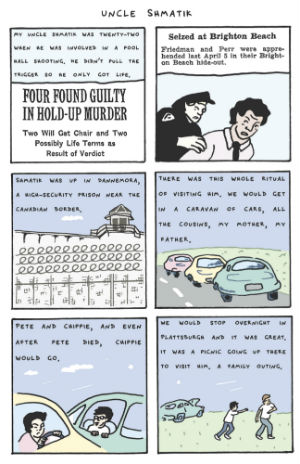

The struggle of people trying to escape their lot in life looms large in the story of Herb’s extended family. As the sons of an overworked immigrant tailor, Herb’s father and his brothers all end up involved in crime. This goes poorly not only for Jerry. His brother Pete commits suicide after getting into deep gambling debt while his other brother Shmatik faces life in prison for his part in a shooting. The sins of the father are then visited on the children as we see Herb’s siblings try to escape their difficult upbringing by fleeing to the army or through substance abuse. His mother also appears to be trying to escape her painful upbringing, though she only ends up repeating the cycle of despair and abuse with her own children.

In a telling anecdote Herb remembers how his father and mother were both connected to notorious gangster Bugsy Siegel. The story of how Siegel had Jerry both hide murder weapons and deliver bags of food to poor Jewish families during the depression highlights the way in which criminality can take on a substantially different meaning for the underclass. Even decades later Herb’s mother speaks of Siegel with reverence. This acceptance of criminality as a way of life is echoed in the story of how Herb’s family turns visits to his uncle in jail near the Canadian Border into a caravan vacation. Hemmed in by poverty, frustration, and casual violence, it unsurprising that members Herb’s family and community turn to such get rich quick schemes as crime and gambling to try and escape.

For Herb escape comes in a different form. Through a combination of (the at the time radical treatment of) therapy and an arts scholarship to NYU, he is able to get away from his dysfunctional family and start living his own life. This starts to set up a divide and Perr will explore this idea in greater detail in later issues of the series, the contrast between the desperate lives of his parents versus those who have found a way to fully express their frustrations with the world. Here it is contrasting the cycle of violence represented by his parents with the stability and opportunity represented by the therapists, academics, and artists Herb is meeting. When Herb finally breaks with his father through his own outburst of violence, the moment feels earned. With all that he has had to endure, and all he has waiting for him, Herb needs to take both his future and his father into his own hands.

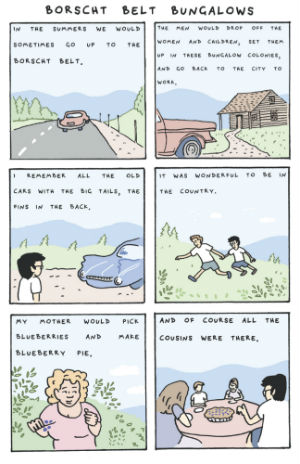

Outside of the central family drama, Herb also recounts more pleasant memories of his family’s vacations to bungalow in the Borsch Belt or his youth in Brighton Beach. Another vignette examines the life of Herb’s favorite and possibly gay uncle who danced in the Catskills. These and other memories of a bygone era have a softer more nostalgic tone with nicely matches Perr’s lightly sketched, pastel colored cartooning. What is surprising is how well this style work on the more dramatic material that makes up the bulk of Hands Up, Herbie! While the pacing is excellent in its intercutting between modern day Herb and recreations of the past, within panels the story is told with minimal flourish.

Perr’s framing most consisting of upper body shots or facial close-ups. Fortunately he is able to capture the pensiveness, the frustration, and the long buried sadness in his subjects alleviating the need for much cinematic story telling. His renderings are simple, but never feel incomplete or haphazard. The soft blues and reds of the background blending with pink and beige tones of the characters does a lot to keep the frame from feeling empty. Though the panels where Perr trains the camera on scenery or period cars stand out nicely in their technical proficiency and expansion of the color palette, adding flavor to the less emotionally charged stories Herb tells.

For an early work, the first issue of Hands Up, Herbie! is a nice showcase of Perr as a cartoonist. He fully taps into comics’ ability to not only document but give life to a subject’s words. He makes smart editing choices both within a scene and as part of the issue’s overall structure. Equally smart are Perr’s choices in maximizing the effectiveness of what he is capable of doing with his current rendering skills. It will be interesting to see how Perr moves forward with this project as well as how he applies his abilities to other stories.

Joey Perr (W/A) • Self-Published $10.00

Review by Robin Enrico