There are certain ideas and images that come to mind unbidden whenever the words ‘Harlem Renaissance’ appear. A lot of this has to do with how the 1920s and 1930s have been interpreted and reinterpreted by scholars of art, music, literature, and history. What they conjure is an amalgamation of glitter and grime, something dark yet compelling. It’s interesting to consider how we have all been inadvertently exposed to that era, thanks to how art trickles down to influence future generations. Contemporary music, for example, bears the mark of sounds first created by Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong.

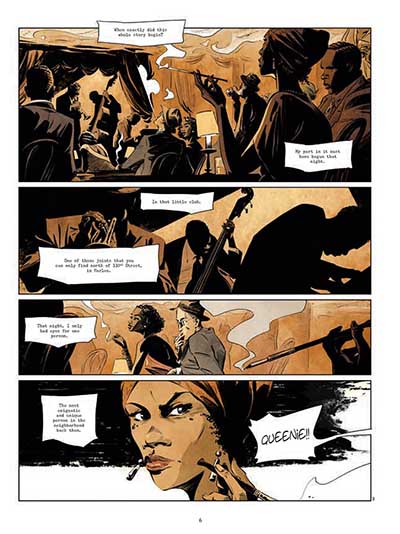

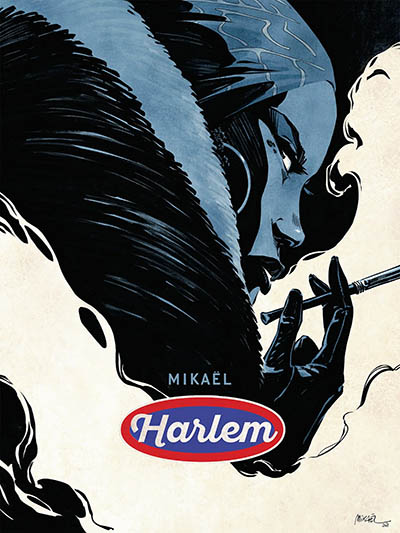

What doesn’t get as much attention as the culture, however, is its impact on people alive during those years. That is what makes Harlem—the third part of a trilogy set in New York by French-Canadian artist Mikaël—special. At first, it appears to be a straightforward tale of crime in a big city, but slowly evolves into an insightful peek at what it meant to be Black in America at a time when larger forces were shaping the consciousness of that nation. Mikaël adds another tantalising element to his choice of subject by making his protagonist a female immigrant.

Having said that, Stephanie St. Clair is no ordinary woman. She was described, variously, as a racketeer, activist, and gambling boss. Mikaël’s protagonist Queenie is fictional, but the sources he lists (Shirley Stewart’s The World of Stephanie St. Clair: An Entrepreneur, Race Woman and Outlaw in Early Twentieth Century Harlem, Raphael Confiant’s Madame St-Clair, LaShawn Harris’s Sex Workers, Psychics, and Number Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy) make it obvious who she is based upon, along with other characters she comes into contact with as she tries to make a living in a city long used to male control.

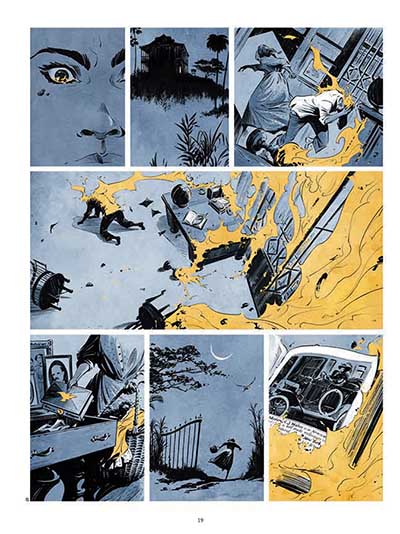

Queenie isn’t just trying to run an illegal lottery in Harlem; she must also contend with the end of Prohibition, systemic corruption in the police force, the impact of the Depression on politics and race relations, and a ruthless competitor in the form of a bootlegger named Dutch Schultz. It makes for a story as compelling as it is necessary, revealing aspects of Black history that are often glossed over by books and reports more interested in the bigger picture.

Mikaël’s trilogy began in 2017 with Giant, about a gigantic Irish immigrant struggling with homesickness while helping to build skyscrapers in the new world. This was followed by Bootblack in 2019, set during the Great Depression, about an orphan who loses his soul to the mafia. Harlem, translated from the French by Tom Imber, followed the same two-part format when it first appeared in 2021. Mikaël’s style is recognisable by now, which is no mean feat for a self-taught artist. He is not afraid of bold colours and strong lines, and his panels of cityscapes bear the mark of close study, a fact born out in the delightful preparatory sketches included at the back of the book. He has cited his influences in the past—François Boucq, Ralph Meyer, Giraud, and Sean Murphy, among others—but Harlem is a work of quiet confidence from an artist who has clearly come into his own.

Mikaël (W/A), Tom Imber (T) • NBM Publishing, $27.99

Review by Lindsay Pereira