MYRIAD WEEK!

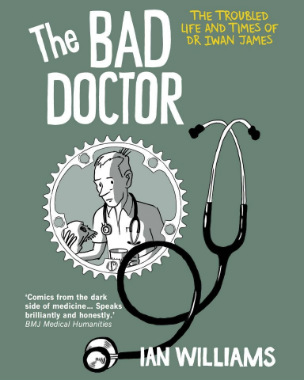

He’s the gent who gave us the term ‘graphic medicine’ and the original driving force behind the respected website of the same name. He’s also a comics self-publisher who was picked up by Myriad Editions after being a finalist in the 2012 Myriad First Graphic Novel Competition and whose debut graphic novel The Bad Doctor will be followed up by sequel The Lady Doctor on the Myriad publishing schedule. And added to all that he’s also a practising GP.

Who is he? Well in his self-publishing days you would have known him as Thom Ferrier but that pseudonym has been kicked to the sidelines and his vital contributions to the ever growing area of comics and medicine are now attributed to his real name – Ian Williams. Today in an uncompromising and candid interview (as part of our ongoing Myriad Week series of articles) I chat to Ian about his debut graphic novel and its sequel, using comics as a form of activism, and the autobio elements of his work…

ANDY OLIVER: By way of introduction can you give us a little background on your entry into comics, your early self-publishing days and the story behind your days as The Artist Formerly Known as Thom Ferrier?

ANDY OLIVER: By way of introduction can you give us a little background on your entry into comics, your early self-publishing days and the story behind your days as The Artist Formerly Known as Thom Ferrier?

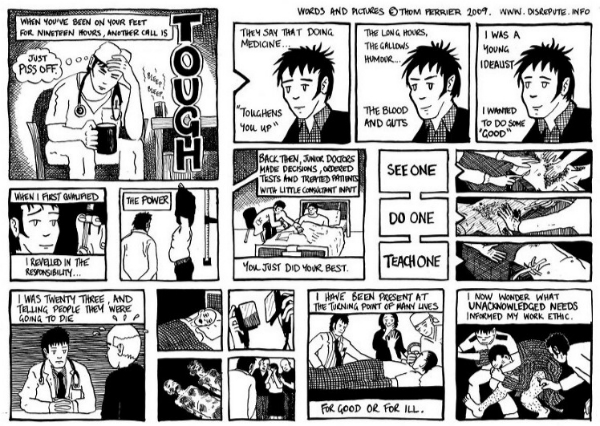

IAN WILLIAMS: It was a strange and circuitous route. I trained in medicine, as you know, and became a doctor. After med school I went to art school, part time, and studied painting and printmaking. I developed a side career in fine art, with some modest success. I then did an MA in Medical Humanities – that is looking at healthcare using the conceptual tools of the arts and humanities. I was trying to find the common language between the two sides of my career.

When I was considering what to write about for my dissertation I happened upon Brian Fies graphic novel Mom’s Cancer in the Tate Modern bookshop. I was into comics when younger and had been reading graphic novels but this was the first time I’d seen a comic about illness. I bought it and decided to write about illness narratives in comics. I set up the Graphic Medicine website and began to review other works about illness and healthcare. At some point, reading all these – mostly autobiographical – works, I had the thought ‘I could do that’ which is a very doctor-like way of thinking.

I started to make a few strips about being a junior doctor, giving vent to some of the trauma and conflicted shit that that particular job subjects one to. People seemed to like it. I produced various strips and self-published comics and, in the inclusive community of autobiographical comics, where flaws and failure can be currency, I tentatively started to talk about my own history of mental health problems, which I had kept absolutely hidden until then. I have to give a big nod to Nicola Streeten and Sarah Lightman, here: I spoke, early on, at Laydeez do Comics and realised that there were like-minded people out there who took comics, politics and social issues seriously. They had a big influence on me. I also met Myriad Creative Director Corinne (Pearlman) at Laydeez.

We have you to thank for coining the now familiar term “graphic medicine” – a strand of comics narrative that has brought in a whole new readership to the form over the last few years. Why do you think that sub-genre of the graphic memoir has resonated with new readerships to the degree that it has? And what is it about the unique properties of comics that make it such a suitable form for communicating the emotional impact of those stories?

You are welcome. I think it is partially as a result of the ‘rise of the graphic novel’ as a kosher art form and the championing of the medium by broadsheet reviewers, but also due to the discovery of comics by young people of a much broader and more inclusive demographic than what we might have thought of as the ‘typical’ comics reader. Women have played a big part in this change, and if you look at the titles being published, many of the works specifically reflect the feminine experience.

Comics are complex and packed with information, yet easily absorbed, and can play around with time and internal and external worlds. I think it is this playfulness that lends itself to autobiography so well. As Charles Hatfield points out, no one has to get too hung up on issues of truth and fiction, they can be merged to make a the best story, and the obvious constructedness of the comic form allows a large degree of artistic license when compared to prose or documentary film-making.

As mentioned, you founded the Graphic Medicine website in 2007 which you now run with MK Czerwiec. What was the philosophy behind the site?

I started the site as a resource. It was a kind of procrastination project. I had so many notes that I had made whilst reading books for my MA dissertation that, rather than get on and write the thing, I set up the website and called it Graphic Medicine. I felt that comics could play various roles within the theatre of healthcare: as education for professionals; as an insight into the patient experience; as social documents of healthcare systems, as help and education for service users, etc.

Can you tell us about the objectives of the annual Graphic Medicine Conference and some of the themes it’s covered over the years?

The main objective is to bring together like-minded people who are interested in what goes on at the intersection between the medium of comics and the discourse of health, illness, disability and care. So far it has achieved this objective admirably, with each conference generating a wild buzz of excitement as new conversations and collaborations are started. We try to have a loose theme for each conference. This year, in Seattle, the theme is accessibility, considered in a broad context. Last year, in Dundee, it was performance, and previous themes have been spaces of care, public health and ethics. The themes are usually interpreted in many ways and we always receive a broad range of proposals for academic talks, workshops, performances and reports.

How do you see graphic medicine in terms of activism, and its role in changing perceptions and opening up discussion? And would you define your Guardian Sick Notes strips – your weekly comic on the state of the NHS – in those terms?

Autobiographical comics, as I see it, comes from the underground tradition, where radical ideas and uncensored content was prized. Then there is the rich history of satirical cartoons.

The novel and engaging form of comics perhaps lets people engage in political issues when they would be less likely to read an essay or non-fiction book.

It was fun doing the Guardian strips and seeing how far I could push things. At one point I had Jeremy Hunt on a scaffold with a noose round his neck. That got vetoed. My proudest hour, however, was sneaking in a barcode to one of the strips which, when scanned, said ‘Fuck the Tory Cunts’. The strip was duly posted online and printed in the paper. I thought I might get sacked for that, but when the editor found out, he seemed to think it was quite funny.

Your association with Myriad goes back to your shortlisting for the 2012 Myriad First Graphic Novel Competition with your first graphic novel The Bad Doctor being the result of that. What’s the premise of the book and what are its core themes?

The Bad Doctor is a fictional story about medicine, cycling, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and heavy metal. It has, however, autobiographical elements in that I am a doctor who is into cycling, suffered disabling OCD as a younger man, and was into heavy metal when I developed the OCD. The protagonist, Iwan James, is not me, however, or at least his life story (married, with grown-up twins) is not mine. He does share a lot of my experiences, however.

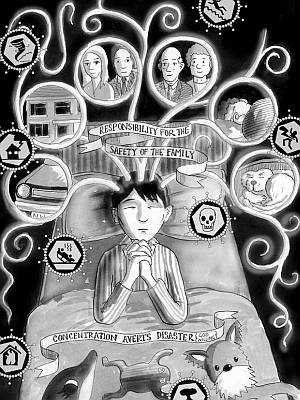

There are three threads to the story: tales from the surgery (in which I strive for a certain humorous verisimilitude); flashbacks to Iwan’s earlier life and OCD, and episodes of cycling during which he puts the world to rights with his buddy, Arthur. This last thread was a device, really, which allowed me to draw the Welsh countryside, and bikes, and to articulate Iwan’s thoughts and worldview. I decided not to use any narration or thought bubbles in the book, although in the OCD bits there is some internal monologue. Everything is done in immediate scene.

Iwan’s OCD focuses on ideas of magic, religion, luck and the occult, and so during the book I alluded to the links between natural magic and the occult sciences and modern day medicine. I guess I wanted to show Iwan as a troubled human being, who is trying to do his best for his patients despite his psychological problems.

The Bad Doctor is an often darkly funny read and a book that consistently makes use of the particular language of comics to advance its themes. But it’s in those sections dealing with Iwan’s OCD that it’s most memorable – the diagrammatical pages that emphasise his childhood fears to such great effect. Was there a sense of the cathartic in depicting those sequences on the page with such an empathetic clarity?

I think that in making those tableaux, which often have an alchemical or kabbalistic feel, I was trying to make something that was a source of shame and misery into something of beauty. In doing so I was owning it, and neutralising it. I have to point out that I would not now qualify, by the various diagnostic criteria used, as having OCD – it burnt out of its own accord in my thirties – but I do retain the traces of it, and it is want to rear its ugly head at times of stress.

OCD is rated by the World Health Organisation as being one of the ‘top ten’ disabling conditions. It is something like living in a hell of one’s own making. Many people are obsessive, or compulsive, but it is the disorder bit of the label that is most relevant. One is tied up in mental bonds that rapidly morph and grow and change their nature. It is an exhausting process, but also, in its own perverse way, a very creative one. I suppose I was trying to use comics to show what it was like. For me, at least. It was cathartic in the sense that it allowed me to talk about something I had never articulated before.

OCD is rated by the World Health Organisation as being one of the ‘top ten’ disabling conditions. It is something like living in a hell of one’s own making. Many people are obsessive, or compulsive, but it is the disorder bit of the label that is most relevant. One is tied up in mental bonds that rapidly morph and grow and change their nature. It is an exhausting process, but also, in its own perverse way, a very creative one. I suppose I was trying to use comics to show what it was like. For me, at least. It was cathartic in the sense that it allowed me to talk about something I had never articulated before.

You have a follow-up to The Bad Doctor coming from Myriad. How is The Lady Doctor linked to the world of Iwan James?

The Bad Doctor was the first book of a planned trilogy. It featured a practice of three doctors: Iwan James (the main protagonist) ; Lois Pritchard (the eponymous Lady Doctor) and Robert Smith who will take centre stage in the third –as yet untitled – book. I may call the third one ‘The Total Bastard Doctor’ or something similar.

The Lady Doctor (sample pages below) features Lois Pritchard as the central character. It is a much more political book with themes of class and cultural struggle (getting in some stuff about the miners strike of 1984), generational and sexual divides and the unconscious hypocrisy at work in many aspects of healthcare today. Even in our beloved NHS…

As another creator who moved from self-publishing to being picked up by a publisher how did you find the experience of working with an editor for the first time? How did it change the way you approached the work?

I used to love the fact that self-published comics tend to be free from editorial ‘interference’, seeing them as a kind of pure, subjective, articulation of the author’s worldview. However… my experience of working with my wonderful editor, Corinne Pearlman, has taught me that most narrative pursuits can be vastly improved by a skilled editor. We are blind to the holes in our own work, in the same way we are often blind to our own prejudices and assumptions. The Bad Doctor evolved and grew as a book with Corinne’s input. The end product was much, much better than it would have been without her.

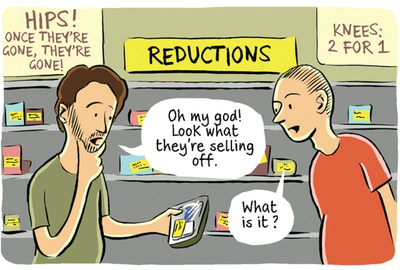

Interiors from the upcoming The Lady Doctor

Can you give us some insights into your own creative process and how you combined ink illustrations with digital embellishments on The Bad Doctor?

My ideal process, which I am using for The Lady Doctor, is to draw the line work in ink with a brush and fountain pen, on A3 bristol board. Scan that in as a bitmap. Clean it up and colour it in photoshop. For TLD I am using line and a flat, single, spot colour for background shading. With The Bad Doctor I was hopelessly behind schedule, having chucked a grenade into the tranquil waters of my life, shortly after signing the contract, by leaving my former life in North Wales and setting up anew, first in Manchester and then in Brighton. As a result of time constraints it is all a bit of a mixture of ink, wash and digital, which varies throughout the book. I used Photoshop and also Manga Studio, which does a half decent job of imitating ink and wash.

I will say, however, that the idea was that the book starts with two styles – clear line and flat greys for present day, and ink and wash for flashbacks – which gradually merge as the story progresses and the timelines merge. The Lady Doctor will not be so complicated.

More interiors from The Bad Doctor

As a practising GP, what have reactions to your work been like from other members of that side of your professional life?

I was terrified before the book came out. I thought people would think I was insane or, worse, had sacrificed a large part of my ‘career’ to produce something that was mediocre or just plain crap. The feedback has been overwhelmingly positive, however, and most of my colleagues have been enthusiastic. Reviews from doctors on Amazon, etc, have vouched for the veracity of the storytelling and patient characterisations. Having said that, not everyone is going to like it and I guess people who didn’t just didn’t tell me to my face.

And, finally, outside of The Lady Doctor are there any other comics projects we should be looking out for from you?

Well, finishing this trilogy will tie me up for a few years, but I am hoping to start doing some more self constructed minicomics. When I started out I was very into the hand-made aesthetic and bookbinding, and did some fancy hand-stitched things with concertina bindings, etc.

For more on the work of Ian Williams visit his website here and follow him on Twitter here.

You can buy The Bad Doctor online here.

[…] Interview: “I Felt that Comics Could Play Various Roles Within the Theatre of Healthcare” – Ian Williams … via @BrokenFrontier […]