It’s not hyperbole to say that without In the Frame creator Tom Humberstone you may well have never seen ‘Small Pressganged’ at Broken Frontier. It was Humberstone’s acclaimed Solipsistic Pop anthology that in one inspirational moment back in 2011 was the direct catalyst for this column. Life is full of these domino effect moments, of course, but Sol Pop’s influence on the direction my subject coverage at BF took is undeniable. And whatever good ‘Small Pressganged’ may have done in raising the profiles of deserving creators and their work in that time is directly attributable to that much missed group project.

It’s not hyperbole to say that without In the Frame creator Tom Humberstone you may well have never seen ‘Small Pressganged’ at Broken Frontier. It was Humberstone’s acclaimed Solipsistic Pop anthology that in one inspirational moment back in 2011 was the direct catalyst for this column. Life is full of these domino effect moments, of course, but Sol Pop’s influence on the direction my subject coverage at BF took is undeniable. And whatever good ‘Small Pressganged’ may have done in raising the profiles of deserving creators and their work in that time is directly attributable to that much missed group project.

I’ve waited nearly four years to write that paragraph and it’s a long overdue acknowledgement.

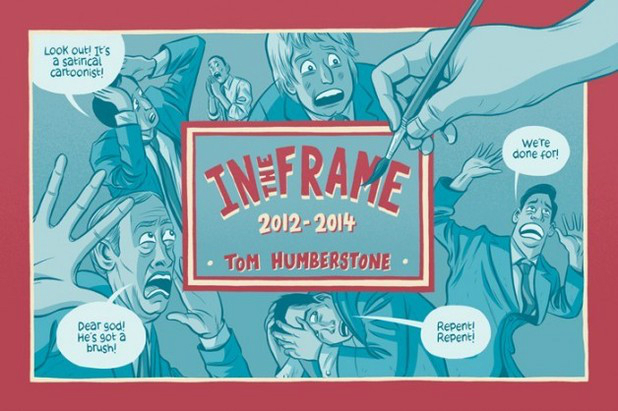

Since 2012 Tom Humberstone has been contributing a weekly topical strip to the New Statesman, one which only recently wrapped up its run. In the Frame collects the best part of two years’ worth of these comics from between 2012 and 2014 in a landscape format self-published volume that, in its physicality at least, has so many echoes of those annual British newspaper cartoon compilations of decades past that older UK readers may remember.

Each week in the feature Humberstone tackled a pertinent talking point from that week’s news whether it be social commentary, overt politics, or the more ephemeral environs of the world of pop culture. There is no standard presentational style that dominates. Sometimes In the Frame works with the rhythmic beats of a traditional newspaper strip – set-up/progression/punchline – while at others it may adopt the superficial structure of a more traditional editorial cartoon, or even seize on familiar elements of comics’ more clichéd conventions for its own ends. Occasionally, where the obvious context for a given strip may not be immediately apparent, a short explanatory note is added.

Each week in the feature Humberstone tackled a pertinent talking point from that week’s news whether it be social commentary, overt politics, or the more ephemeral environs of the world of pop culture. There is no standard presentational style that dominates. Sometimes In the Frame works with the rhythmic beats of a traditional newspaper strip – set-up/progression/punchline – while at others it may adopt the superficial structure of a more traditional editorial cartoon, or even seize on familiar elements of comics’ more clichéd conventions for its own ends. Occasionally, where the obvious context for a given strip may not be immediately apparent, a short explanatory note is added.

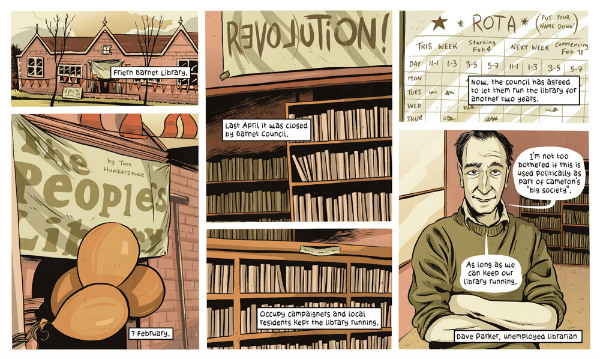

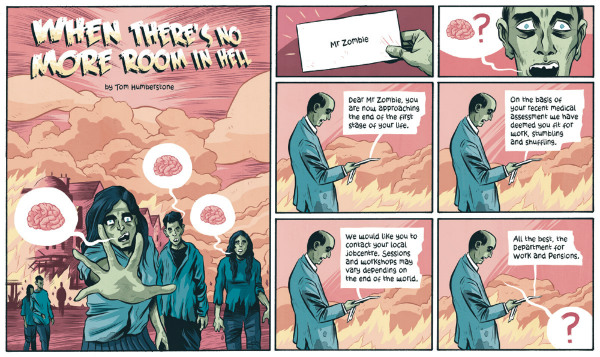

There’s a narrative and structural diversity in the material here that makes In the Frame a fascinatingly unpredictable read; an unlikely eclecticism, perhaps, from one artist with a basic brief to present an easily consumable weekly topical strip. The comics range from the very human – a modest but incredibly poignant piece of graphic reportage about volunteers struggling to keep the Friern Barnet public library open (above), for example – to the wildly extravagant. That’s well represented by supernatural send-up ‘When There’s No More Room in Hell’ (below) in which the Department of Work and Pensions decide that even in the chaos of a zombie apocalypse the shuffling undead are still fit for employment.

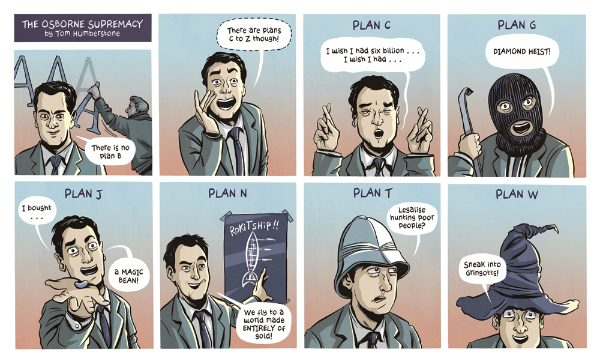

This is Humberstone’s great skill as a satirist and commentator. He has an intuitive understanding of how to communicate the crux of an issue – of which subjects deserve a quieter, reflective focus and which can be lampooned with a frenetic energy. In that latter category is the manic humour of ‘The Osborne Supremacy’ (below) with the chancellor’s increasingly frantic and ludicrous solutions to the financial crisis. In the former, ‘Retrospective’, which deals with the 2013 Lichtenstein exhibition at the Tate and mirrors the controversy surrounding the artist’s work with a playful use of panels within panels and a narrative within a narrative.

This is Humberstone’s great skill as a satirist and commentator. He has an intuitive understanding of how to communicate the crux of an issue – of which subjects deserve a quieter, reflective focus and which can be lampooned with a frenetic energy. In that latter category is the manic humour of ‘The Osborne Supremacy’ (below) with the chancellor’s increasingly frantic and ludicrous solutions to the financial crisis. In the former, ‘Retrospective’, which deals with the 2013 Lichtenstein exhibition at the Tate and mirrors the controversy surrounding the artist’s work with a playful use of panels within panels and a narrative within a narrative.

In the Frame is two years of modern living that encapsulates everything from our most trivial concerns to our most profound ones, all embodied in around 90 pages of snapshot comic strips. The life expectancy of a viral video, the lapses into mindlessness of 24-hour news coverage, support groups for unloved punctuation in a social media-obsessed age are counterpointed by events in Syria, the education crisis and institutionalised sexism.

Humberstone has a particular gift for couching events in more familiar and humorous frames of reference that speak to the audience in a manner that a direct and blatant approach could not, making his point with greater potency as a result. Sanctions against Russia taking the metaphorical form of a Putin as a rebellious child confined to his bedroom (below), or apathy about the relentless tide of social injustice presented as a super-hero comic.

Humberstone has a particular gift for couching events in more familiar and humorous frames of reference that speak to the audience in a manner that a direct and blatant approach could not, making his point with greater potency as a result. Sanctions against Russia taking the metaphorical form of a Putin as a rebellious child confined to his bedroom (below), or apathy about the relentless tide of social injustice presented as a super-hero comic.

It’s important, as well, to remember the original home of these strips and the broader readership they were aimed at. There’s a precise skill to working on the limited canvas of a weekly strip that is vital in communicating information to a potentially non-traditional comics audience; a readership not necessarily conversant in the language of the form. A too elaborate or complex use of the narrative techniques of comics could have been inappropriate in the circumstances, and yet Humberstone still manages to be constantly inventive and imaginative in his manipulation of such a restricted narrative space.

There’s a subtlety to his work. An ability to cut away, to juxtapose, to contrast, that playfully toys with what the medium can do but never forgets its need for accessibility; something that is mirrored in the crispness and lucidity of his visuals. And “accessibility” is very much the watchword here. Humberstone’s tone is not so much caustic as quietly observational. He often structures his commentary so that it’s more about the absurdity of a situation, ensuring its effectiveness by being more detached and pithy than cutting. Yes, there’s anger here. But if it’s not exactly a subdued ire then it’s certainly controlled in delivery, with a resigned and weary calm to it. It makes each strip all the more powerful in communicating its message with a clarity and passion that ruthless and unrestrained invective could never muster.

There’s a subtlety to his work. An ability to cut away, to juxtapose, to contrast, that playfully toys with what the medium can do but never forgets its need for accessibility; something that is mirrored in the crispness and lucidity of his visuals. And “accessibility” is very much the watchword here. Humberstone’s tone is not so much caustic as quietly observational. He often structures his commentary so that it’s more about the absurdity of a situation, ensuring its effectiveness by being more detached and pithy than cutting. Yes, there’s anger here. But if it’s not exactly a subdued ire then it’s certainly controlled in delivery, with a resigned and weary calm to it. It makes each strip all the more powerful in communicating its message with a clarity and passion that ruthless and unrestrained invective could never muster.

In the Frame eschews the traditional traits of political cartooning – the easy descent into grotesque caricature and easily spat bile – for something that is all the more probing and successful for its subtlety and nuance. A thought-provoking dissection of 21st century life that never pretends to have all the answers but asks all the right questions regardless. This is a magnificent showcase for Humberstone’s quiet but fiercely intelligent social commentary.

For more on Tom Humberstone’s work visit his site here. You can order In the Frame online here priced £12.00.

For regular updates on all things small press follow Andy Oliver on Twitter here.