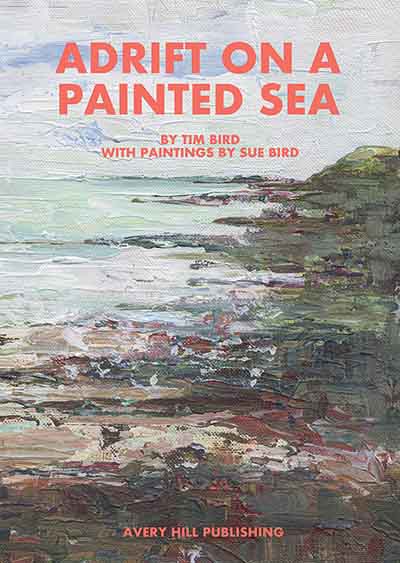

If you’ve been following the Avery Hill story since the very beginning you will be aware that artist Tim Bird has been part of their publishing output since the very early days of quirkily-themed zines and DIY culture-style comics anthologies. Bird’s work for AHP began with work in their original flagship Tiny Dancing series before moving on to his Grey Area comics and the critically acclaimed The Great North Wood. After a few years of prolific comics self-publishing his new Avery Hill title Adrift on a Painted Sea (currently crowdfunding on Kickstarter) looks set to be his most personal work to date.

Here’s the publisher description:

A poignant, thoughtful graphic memoir that explores family, loss, and art through the author’s relationship with his mother, who painted as a hobby throughout her life.

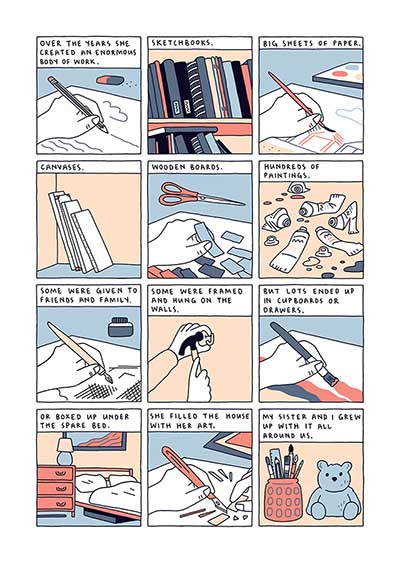

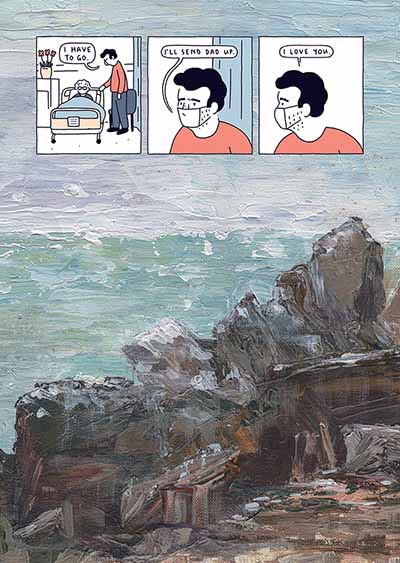

Sue Bird was always painting: botanical art, landscapes, still lifes, and especially the sea.

She took classes, kept countless sketchbooks, and filled the house with art. From their neighborhood to their family trips, all the moments of her life were memorialized in her artwork. Throughout her life, she never sold a piece—she gave art to family and friends, and shared her work online, but never received wider recognition for her work.

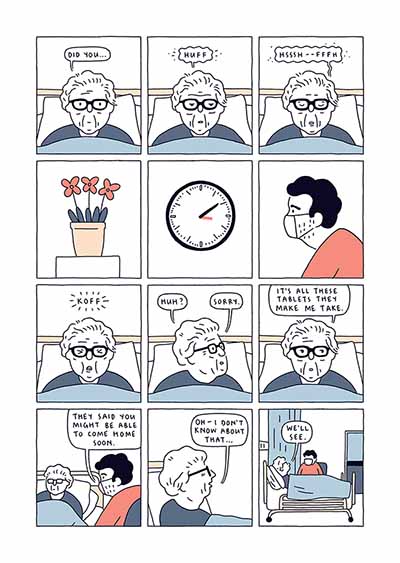

This graphic novel by her son, Tim Bird, explores their family life and her creative explorations through a mix of her paintings and Tim’s comics, depicting their relationship and her life from teenagehood to her struggle with cancer at the height of the covid pandemic. After her death, this graphic novel at last showcases her work.

Those wanting a comprehensive look at the Tim Bird back catalogue to date are pointed to all our tagged BF articles here. With all those years of Tim Bird BF coverage in mind we’re very pleased today to be able to present this exclusive chat between Tim and AHP’s Katriona Chapman about Adrift on a Painted Sea.

KATRIONA CHAPMAN: I love that this book has a really universal theme. Most people will have to deal with ageing parents/the death of parents at some point. This book feels like such a powerful tribute to your mum and her art! Was it difficult to tackle such a personal moment of your life in an autobiographical book?

TIM BIRD: In one sense it was a nice opportunity to spend time looking back at her work and her sketchbooks. The hard part was drawing her looking old and frail in the hospital and showing the moment of her passing away. I think this is where comics has an advantage as I was able to use a visual metaphor to illustrate this moment, which gave me some distance between the reality of the situation and the way I tell the story.

CHAPMAN: I’ve heard some creators who work in autobiography say that they find the process cathartic, but I’ve also heard others say that’s not necessarily the case for them. I personally think I find art helpful as a way of processing difficult things… if I can write and draw it, I think it helps me to process and gives me an outlet for the feelings. What’s your experience of this?

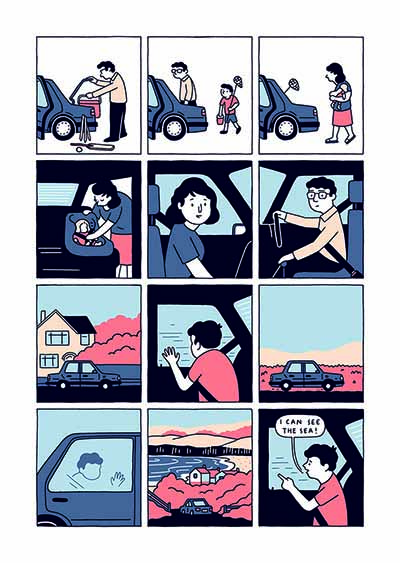

BIRD: I definitely used the process of making the book as a form of therapy! I threw myself into drawing it not long after she’d died and started by working on the scene where I travel up the motorway to visit her in hospital, which appears in the second half of the book. I was lucky that I was able to be with her, along with my dad and my sister, when she died, and to be able to tell her that I loved her and say goodbye, but writing those things in the book seemed to set them in concrete and helped me process my feelings. I found the creative process cathartic, but worried about what my dad and my sister would think – whether they felt it represented my mum, or if I’d just used her work to tell my own story. In the end, they’re happy with what I’ve made and have told me they think it’s a nice tribute to her.

CHAPMAN: Knowing you as a creator who’s always been interested in psychogeography, (the effect of geographical locations on the emotions and behaviour of individuals,) I thought it was wonderful that so many of your mum’s paintings were landscapes. It made me think that there was a strong parallel between her expressing her love of these places through painting, and your work in comics. Was that something you ever talked to her about?

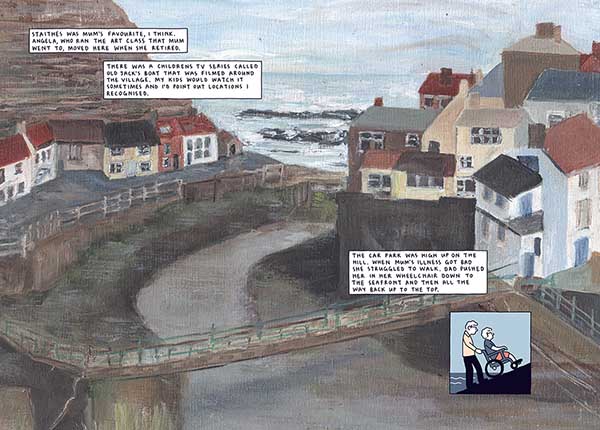

BIRD: My mum made hundreds of paintings, not just of the sea. I suppose selecting these ones and choosing to focus on that part of the landscape says a lot about me. The sea is regularly used as a metaphor for grief, and I was leaning into that idea too. My mum loved nature and the outdoors. She used to go on long walks in the Yorkshire Dales and by the coast. One of the hardest parts about the later stages of her illness was that she couldn’t walk very far. My dad had to push her along coastal paths in a wheelchair. I talked to her about psychogeography when I was discussing some of my earlier comics with her, but I don’t think it’s something she really connected with. She was a fan of nature-writing, though – writers like Melissa Harrison and Helen Macdonald. I remember her reading The Old Ways by Robert Macfarlane, which touches on psychogeography. I’m sure her love of the outdoors inspired my work.

CHAPMAN: One thing I enjoy in your work is that it feels very rich with meaning. I find that it sparks lots of ideas as I read. One thing that came up for me was that in spite of similarities that exist between people – for example within a family – everyone is an individual and everyone’s sense of the world is their own. In spite of you seeming to have a shared love of art with your mum, you describe as a child feeling alienated by art galleries. And again when talking about the castles of the Northumberland Coast, you said that as a child you were more interested in exploring the inside of your family’s caravan. Again that plays with the idea of how human beings interact with the spaces around them at different points in their lives, and how those relationships between people and places are all very unique! Is creating multiple levels of meaning something you aim for in your work, and if so how do you approach it?

BIRD: I really like how visual art, including comics, can be so open to interpretation. I do try and leave some ambiguity in my comics – or at least not spell everything out really obviously. I’ve learnt to use images to create narratives, rather than text – there can be a temptation to over-describe a story in comics by including long captions. I try and think of my audience when I’m creating a comic, and this is where, perhaps, different levels of meaning come into the story. I have two audiences for this book – people who knew my mum and her work, and people who didn’t. I wanted to make sure it worked for both sets of readers – that it would be a tribute to my mum’s work for those who knew her, and that it would work as a cohesive comic for everyone else.

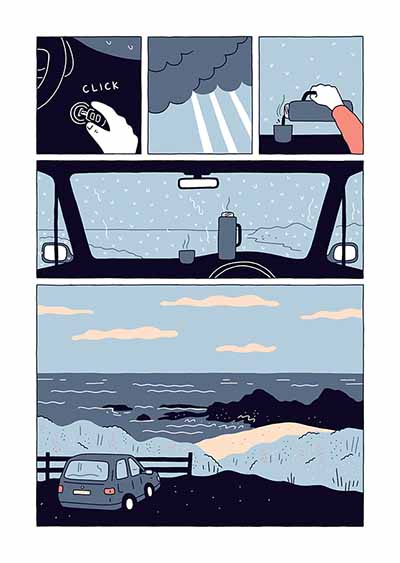

CHAPMAN: I love the image in the book of you sitting in your car looking at the sea with a thermos. I included a similar moment in my own book Breakwater, with a character sitting in her car staring at the sea. What do you think makes the sea such a powerful metaphor in art?

BIRD: One of the books I enjoyed reading when I started putting this project together was Looking To Sea by Lily Le Brun. She looks at different works of art which feature the sea and discuses the artworks in a modern cultural context. She talks about how the sea forms part of a national British identity and how we can relate a sense of place to our own memories, so the sea can say something personal to us (recalling childhood holidays, for example) or be the subject of wider societal debate (as the backdrop to immigration or climate change). I think this wide scope of meaning draws artists to depict the sea in many different ways.

CHAPMAN: What does the sea mean to you?

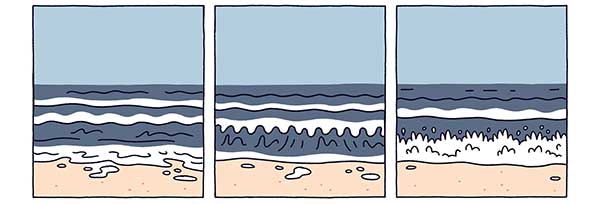

BIRD: This is a tricky question! I kept asking myself “what does the sea mean to my mum” as I was writing the book, and I could never settle on an answer. I think maybe that’s the point though. The sea can be a huge, horizonless place – a blank space that you can project anything onto, and it can reflect back an infinite number of different meanings. Or it can be a postcard-sized glimpse into the past. It changes constantly and means different things in different situations. It can be familiar and calming, or uncontrollable and frightening. One of the first things I drew for the book was a series of waves going in and out on a beach. I found that constant repetition of tides grounding – it seemed to put my sadness into a much larger context.

CHAPMAN: Backers of the Kickstarter for Adrift on a Painted Sea can get a really lovely zine, in which you give some fascinating background information about your creative process. I don’t want to give everything you talk about in the zine away, but I was curious about your editing process. I think you have an amazing economy of storytelling, where everything feels meaningful and exactly in its place, if that makes sense… like there’s nothing superfluous. Do you cut many words/ideas/images as you work, and if so how do you decide what to include and what to cut?

BIRD: Part of the reason why I chose to draw this book digitally was that I found I wanted to move things around as I was writing. I guess because the work is so autobiographical, I didn’t have to think so much about plot points and narrative structure, which gave me a sense of creative freedom. I let the comic develop quite organically. I’d draw pages and panels then move them around so that they made sense in the context of the book. I cut a few bits out because I felt they made the story more confusing, but mainly I do the drawings and try to find ways of making them work. I have quite a minimal drawing style, so I try and make every line count so that the illustrations communicate the message I want them to. Sometimes my drawings look very sparse, but it can take me a long time to get to that point, and I think the sparseness works in this book as it reflects the empty seascapes and gives room for my mum’s artwork to be the centre of attention.

CHAPMAN: The poet Ian McMillan gave you a fantastic cover quote for the book, and you mention in the zine that his book My Sand Life, My Pebble Life was an inspiration as you worked on this graphic novel. What did you enjoy about that book in particular?

BIRD: One of my favourite parts about making comics is the research and background reading. I really like to immerse myself into a subject. I’d read some of Ian’s poetry previously and followed him on Twitter for a while. He seemed to have retained some of the nice aspects of old Twitter – for example, he always tweets how his first cup of tea of the day makes him feel, (at the time of writing “ordinary and extraordinary at the same time”.) I’d seen him post about his prose book, My Sand Life, My Pebble Life, and decided to read it when I’d settled on the idea of making my own book about the sea. Ian’s book is a collection of reminiscences about childhood trips to the sea – usually the same part of the coastline in North Yorkshire that I’d visited with my family as a child. I loved how he celebrated the ordinary, and his nostalgic writing. Nostalgia is a theme that recurs regularly in my own work.

CHAPMAN: One of the most powerful moments in the book for me was when you talk about the finality of death, and the fact of those mysteries that remain when someone passes away, and you can no longer ask them anything. Did you know that you wanted to make this book before your mum passed away, or did the idea come later? I’m curious if she ever knew that you were going to make a book incorporating her art.

BIRD: My mum had been creating art for her whole life and almost all of it just got shoved into cupboards and drawers. I always thought it deserved to be seen by a wider audience. I talk in the book about how I tried to set up a website for her to showcase her art, and later helped her set up an Instagram account. It wasn’t really until her illness had deteriorated badly that I settled on the idea of combing her paintings with my comics in some way. I spoke to her about it, and she liked the idea. At that point it was still very conceptual – I didn’t have a structure outlined. My initial idea was to make a series of poster zines – each one would have one of her paintings on one side and could be folded to create a booklet with a short anecdote about the sea on the other. It was after she passed away that I decided to structure the narrative around our family life and create a longer book, so I never got to talk to her about that part of the idea.

CHAPMAN: I love the focus on small moments in your book… one of my favourite scenes is the service station scene. Life is lived in these seemingly fleeting, transitory moments which don’t seem particularly dramatic, as much as it’s lived in the ‘big’ moments. What was your reason for including that particular scene?

BIRD:My mum was admitted to hospital with severe pain. It became apparent that she didn’t have long left – it turned out to be about three weeks. I live quite far away from my parents’ house – I’m in Winchester and their house is in Yorkshire. I drove there and back four times during those three weeks. I found it hard to listen to music or the radio in the car, so I spent a lot of time with my thoughts. The only conversation I had during those trips was exchanging a few words with the people who worked in the service station. These moments seemed to take on a huge significance, which I wanted to record in the book. I’m a big fan of Jon McNaught’s work and spoke to him about quietness in comics for an essay I wrote as part of my MA – I think we both share a fondness for quiet moments and liminal spaces that we pass through without noticing. He also included a scene in a service station in his book Kingdom, although the context was different.

CHAPMAN: I think your work captures Englishness in a way… there’s a sense of reserve, and the unspoken which I think is very English! There’s a quiet scene where you watch football with your dad. And the character of your mum in the book doesn’t have a lot of moments where she speaks, but the way you depict her art and her life as an artist really suggest the richness of her inner life. I love that art can be a way of saying things that might be hard to say in words… was that something you found with this book?

BIRD: I know what you mean about a sense of Englishness – I like Martin Parr’s photographs, which combine extraordinary moments in ordinary, quintessentially English settings. I remember going to see his Great British Seaside exhibition with my mum. Art has been a way for both me and my mum to articulate ourselves. We’re both very quiet people – to the point where we both struggled with social anxiety. I think this quietness comes out naturally in my comics – it’s something I’m aware of and try to emphasize. This way of making comics contributes to my voice as a creator. A couple of years ago I self-published a short comic called Wednesday, which was about going to watch Sheffield Wednesday play football with my dad – I think that was a way for me to express feelings that I would struggle to say in person too.

CHAPMAN: What do you hope that people will take away from reading Adrift on a Painted Sea?

The reason for making the book was simply to show my mum’s paintings to a wider audience. I hope that building the comic around the paintings helps to give them some context. I think she was a great artist, and her work deserves to be seen by more people.

CHAPMAN: Finally, do you have any more projects lined up now that you’ve finished this book? Do you know what you’ll be working on next?

BIRD: I’ve been studying an MA in Illustration part-time over the last couple of years, and I’m just coming to the end of it now. As part of my final project, I’ve been making a series of zines about my street. When its finished there’ll be seven or eight short, A6-sized comics, which I hope to collect in a boxset of some sort. I’d like to find a way of publishing them – either with a publisher or self-publishing. As its quite a bit of material it’s likely to be quite costly to print, which will probably put a publisher off, so we’ll have to see what happens with it!

Back Adrift on a Painted Sea on Kickstarter here

Interview by Katriona Chapman