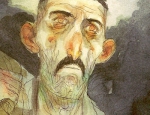

Milan Hulsing is Holland’s best kept creative secret. He is an industrial and innovative creator who approaches each project from a unique perspective. His last graphic novel was an adaptation of Egyptian avant garde writer Mohamed el Bisaties’ novel Al-Khaldiyahe (City of Clay), in a washed-out, impressionistic style (read my review at The Comics Journal) .

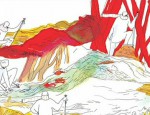

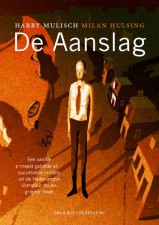

He recently turned his attention to the graphic novelization of De Aanslag (The Assault), by Dutch literary writer Harry Mulisch. It is an emotionally complex and challenging novel, with events playing out against the backdrop of the second world war.

He recently turned his attention to the graphic novelization of De Aanslag (The Assault), by Dutch literary writer Harry Mulisch. It is an emotionally complex and challenging novel, with events playing out against the backdrop of the second world war.

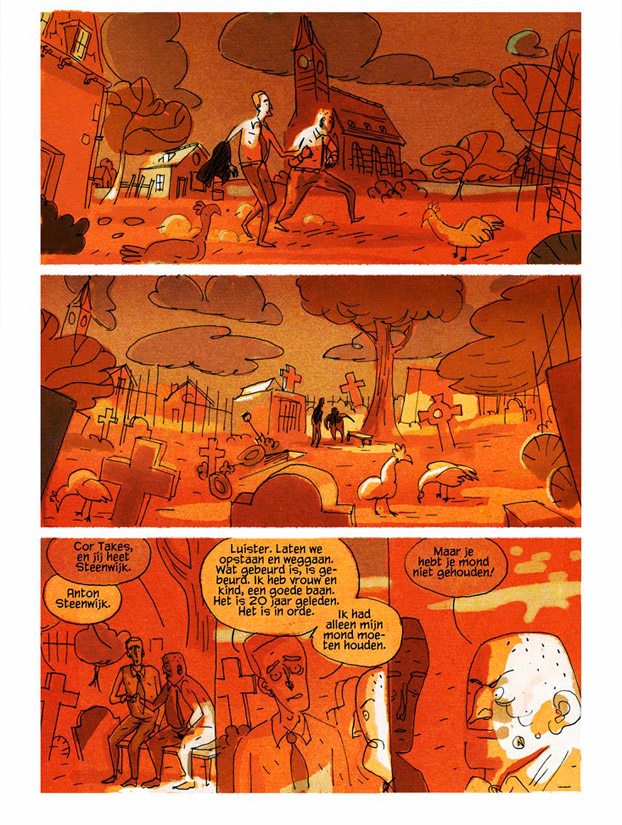

When a Nazi collaborator is shot in front of Anton Steenwijk’s house, he is taken prisoner while his brother and parents are executed. We then follow Steenwijk’s quest up until the 1980s to uncover the truth behind the proceedings. The novel turns into a quiet contemplation of the question of guilt, how the subsequent answers can effectively provide resolution for a trauma of this magnitude and how the perception of events is influenced by an ever-changing context.

Hulsing approached the novel in his own unique way, providing a condensed version of the novel, coupled with personal interpretations of certain scenes. For the visual aspect, Hulsing has once more re-invented itself, and I spoke to him at length about his connection and approach to his latest graphic novel.

Broken Frontier: The Assault is a very challenging and complex novel to turn into a graphic novel. Was your choice based upon a personal connection to the book?

Milan Hulsing: I basically threw myself upon Harry Mulisch’s more experimental novels when I was younger. The Black Light was one of my favorites, and Mulisch wrote this in a very trance-like way, allowing himself to associate at random.

The Assault – written in the 1980s – is a very clear and concise book. Mulisch once stated that he wants to write down simple stories in a complex way, but The Assault has a very strong premise and is written down in the simplest of ways. This of course makes it a good fit for a graphic novel version, even though I prefer his older, more associative work. However, The Assault is such a strong book that it would remain just as powerful a work in this more expressive mode.

As far as a personal connection goes, the book discusses the communist resistance in World War II and the bipartition of the Netherlands’ society after the war. My grandparents adhered to the communist ideals and were resistance fighters during the war. At the same time, my mother was always keenly aware of what communism meant in reality in the Eastern Bloc countries, since she moved from Czechoslovakia to the Netherlands in the late sixties.

My father was very impressed with The Assault and saw parallels with his own life, having participated in the protest marches against nuclear weapons in the 1980s (and we even walked behind Harry Mulisch in that same march!). So I guess there’s some predestination involved.

How did you simplify the novel to a graphic novel script?

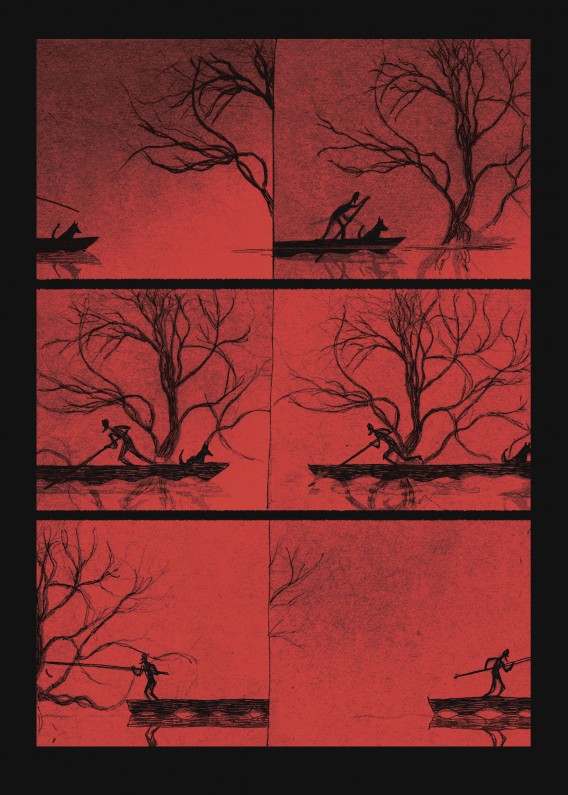

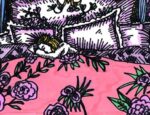

The novel is set partly during wartime and largely in modern times – from the fifties through to the eighties – but it is labeled as a wartime novel, which is a quite popular genre in the Netherlands. Just like the Western genre, there’s a specific design and style that accompanies it, so I naturally opted to go the opposite way.

The novel largely deals with the consequences of war – something I emphasized by having the OGN start in 1952. In the book Anton, the protagonist, has a specific type of memory loss, and the reader starts out on the same foot in my version. By foregoing the war chapter of the novel, it became more adaptable – which does not mean it got any easier. The reader actively needs to reconstruct the events of the book.

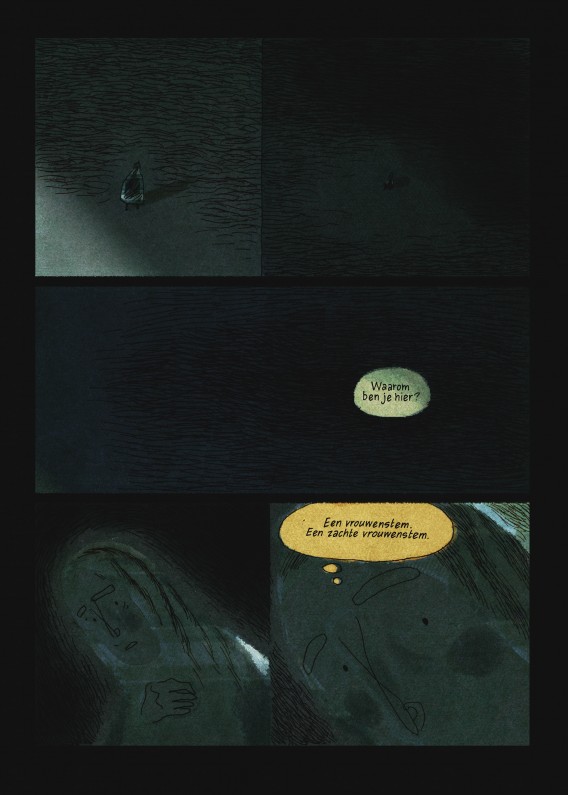

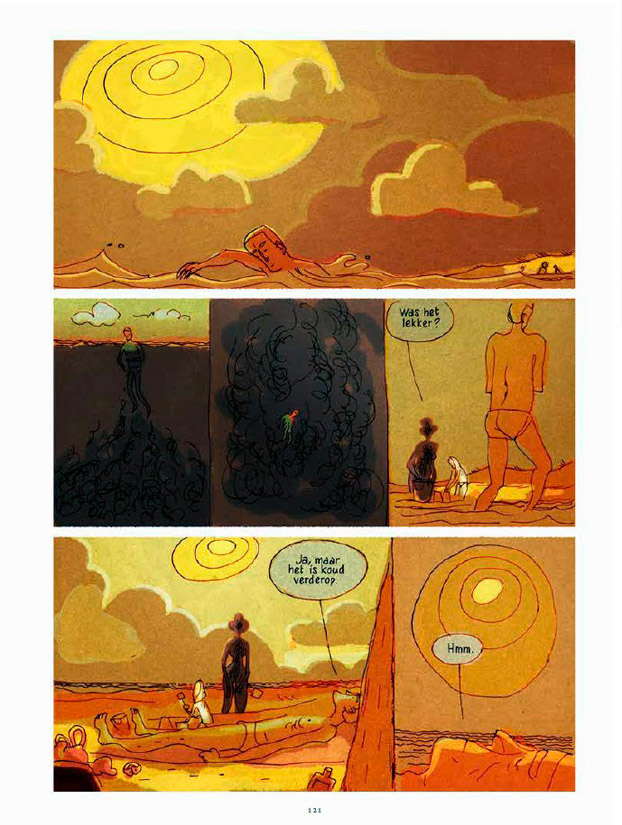

Another important choice was to avoid blocks of text and exposition. The whole of the story is told through visuals and dialogue. Mulisch often used the all-knowing narrator in his books, and I toned all that down in the OGN. This forced me to really transform the novel to the visual medium of comics.

You employ an art style that is deceptively simple but still quite strong emotionally.

I searched for a certain type of ligne claire because I wanted to have closure with the novel, which is written very clearly and in a sort of objective style. There’s a lot of understatement in both our books – there are no extreme camera angles or distorted perspectives, you know? By way of the coloring and lighting effects, I tried to add an expressionistic layer that represents the dark side of the story.

Is the final result mostly done by hand or digital? It’s hard to tell.

The first layout was done completely in pencil, with text layovers. I filled about three sketchbooks doing that. The layouts then served as the basis for the digital coloring. After that I did the final line work on paper, so I kinda went about it in a reverse sort of way. I ‘inked’ the book on a light box with ecoline and pen over the printed coloured pages.

It is quite a dark and fatalistic book. Does this reflect a part of you?

I won’t say it is a fatalistic book, but a book about the consequences of human choices. It is the Germans who decide to execute Anton’s parents and brother, and Anton’s life is controlled by getting a grip on those events. It’s about the fluidity of the past and the future.

The exact circumstances of the horrific events that define Anton’s life are constantly in flux, and even the future is not safe since Anton himself often digresses into ‘what if’ scenarios. At the end of the book there’s even a twist that puts the whole book in a different light.

In terms of themes, I do deviate a bit from Mulisch’s original intentions, like the motive of the dice in the book: ‘What is coincidence?’; ‘Why did the corpse end up in front of our door?’ etc. I believe that Anton is the main character because the resistance fighter Nazi collaborator did end up in front of his door. He’s a damaged individual because he was struck by human choices, not by lightning.

Guilt and moral complexity are central themes in the book.

One of the key remarks in the book is ‘Who performed the deed, performed the deed and no-one else.’ So the book deals not only in guilt but also in taking responsibility.

Anton loses his parents because communists shot a fascist in his street. The shooters are not guilty of shooting his parents, but don’t they at least have some responsibility for the course of the events after the shooting? A solid question in times of occupation and oppression, it seems to me.

Collective punishments are a strategy of the oppressor to confuse the issues of guilt and complicity. The novel makes it clear that you should never forget who the ultimate guilty party is: the oppressor. But this fact does not dismiss complicity and responsibility.

The Assault is basically is an enlargement of the bombing of Dresden – something that quite fascinated Mulisch. An interesting fact is also that the assault in the novel takes place during the latter days of the war, when certain areas of Europe had already been freed from Nazi occupation. Did the deed in any way have any effect upon the end of the war in that area?

Are you ready to dive into another project after this massive undertaking?

Not yet, I must say. I still need to choose between different stories I have lying around. I do have three stories cooking that I wrote myself. After two graphic adaptations of novels, it’s time to dive into my own ideas again.

De Aanslag (The Assault) by Milan Hulsing is published in Dutch by De Bezige Bij. It is a full-color hardcover counting 160 pages and retails for €24,90.

Follow Milan Hulsing at his blog to view his illustration work and keep abreast of up and coming projects.

For more news and info from Europe’s comics community, follow me on Twitter right here.