The period between childhood and adulthood has confounded, engaged, and frustrated the world’s most amazing minds. To write about this transition is to account not just for physical or intellectual changes but shifts in personality that end up defining what a human being grows up to become. This is the liminal space in which Lynda Barry’s work has always shined so brightly.

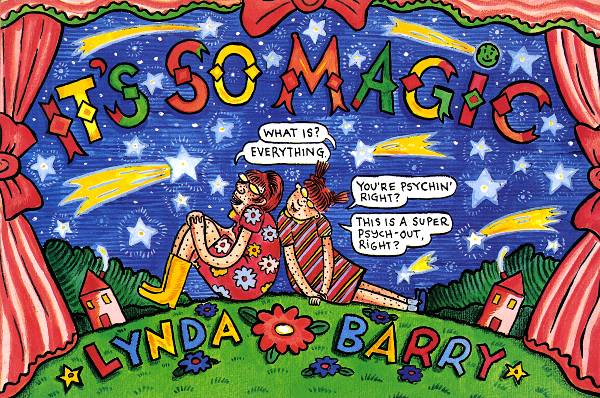

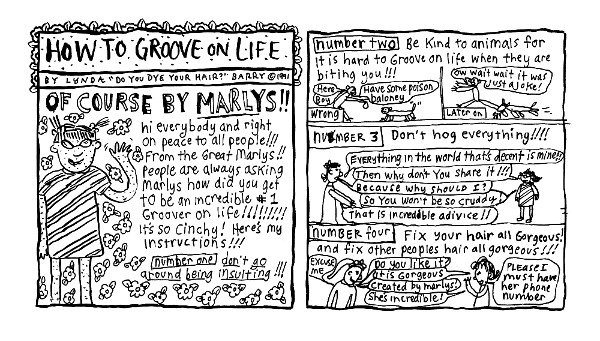

There are all kinds of sensible reasons why Drawn & Quarterly keeps putting out collections like It’s So Magic, based on Barry’s legendary Ernie Pook’s Comeek from the 1990s. For those who love the characters, the most important one is that the comics still resonate so powerfully. There may be little about Maybonne and Marlys Mullen, or their extended family, that most readers who didn’t grow up in America in the 1970s may identify with. And yet, their personal angst and paths of self-discovery gives them a universality of the kind that prompts readers to smile and nod their heads in recognition.

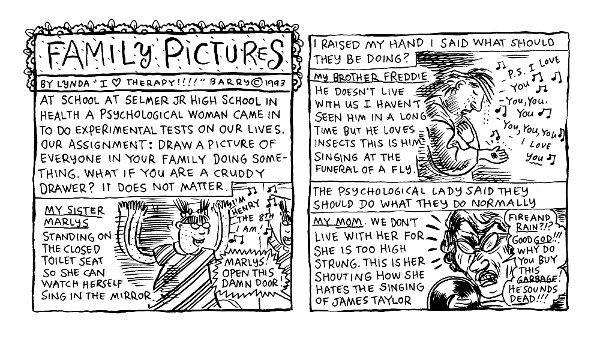

The last collection, My Perfect Life, saw Maybonne navigating life as a teenager in a long-forgotten America. It’s So Magic continues her story while bringing lesser-known family members into her orbit. Living with Grandma Mullen, Maybonne is still writing to her friend Brenda, using letters to try and articulate her unique perspective on the small world she has access to. She paints pithy portraits: of her sister Maryls who stands on a closed toilet seat so she can watch herself sing in the mirror; sentimental brother Freddy who sings at the funeral of a fly; her high-strung mother shouting about how she hates the singing of James Taylor.

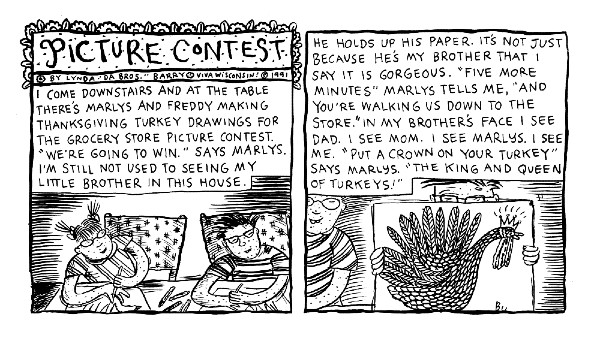

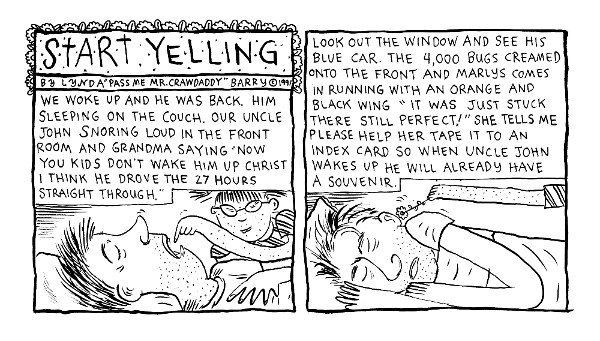

There’s also a lot happening around Maybonne. Her sister has fallen in love with a boy named Kevin, and she has pointed advice to offer (“Why does he make you keep drawing him dragsters, and why does he keep saying it was him who made those drawings? I told her that’s not liking, that’s using.”). Her Uncle John has been outed as a homosexual by her friend Cindy Ludermyer (“Can an uncle still be your favourite uncle even if he’s queer? I say yes logically but right now I say it secretly.”) And her mother wants her children back, which means the girls must get used to their younger brother (“He checked out a book on bats called Bats Bats Bats which he has to do a book report on. A girl named Cindy kicked him in the leg at lunch.”)

Barry’s genius lies in her ability to mimic the way teenagers grapple with concepts they can’t fully grasp, in fits and starts, jumping from topic to topic with no connective tissue. She captures the ennui of being part of something without feeling it, and the timelessness of her characters’ observations, even when they are about specific events like the Vietnam war, lend them a certain poignancy.

Take, for example, the strip titled ‘It’s Nothing’, where Maybonne’s friend Cindy shares her relief at not being pregnant. It is a difficult conversation taking place in the aftermath of what appears to be a case of sexual assault by classmates in a park. “My parents will kill me if they find out I’m not a virgin,” says Cindy, adding that it doesn’t bother her much even as her shoulders are shaking. It is a world of emotion contained in four panels, of the kind that makes us hope Lynda Barry won’t stop giving us more of it.

Lynda Barry (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $21.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira