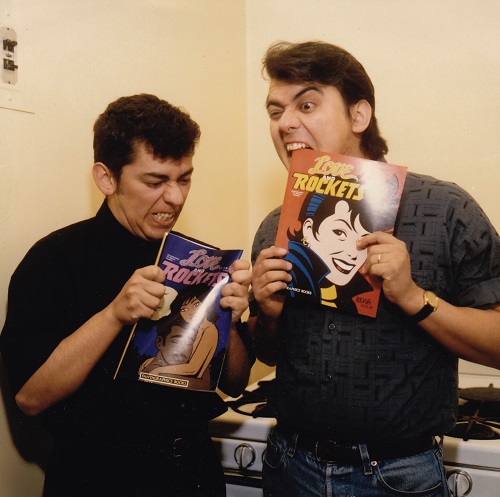

In the four decades since they self-published the first issue of Love & Rockets with their brother Mario, Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez have crafted ground-breaking narratives that rewrote the rules of what kinds of stories comic books could tell. In celebration of the series’ 40th anniversary and the recent release of the Broken Frontier Award-winning Love & Rockets: The First Fifty box set by their long-time publisher Fantagraphics, the Bros talked with cartoonist François Vigneault and discussed the DIY spirit that animates their work, where they would suggest new readers start with their comics, and what inspires them to keep creating.

Photograph by Carol Kovinick-Hernandez

François Vigneault: Congratulations on 40 years, it’s really amazing. Was there a moment where you were like, “Wow, we have something super special here. We’re doing something together that is different”?

Gilbert Hernandez: For me, I was a little surprised that people did respond so well to it. The few people that did read it first, they did catch that right away, and that encouraged us. They thought “We like the characters, we wanna see more.” It’s about the characters, you know, over and over, the characters. That was the most important thing.

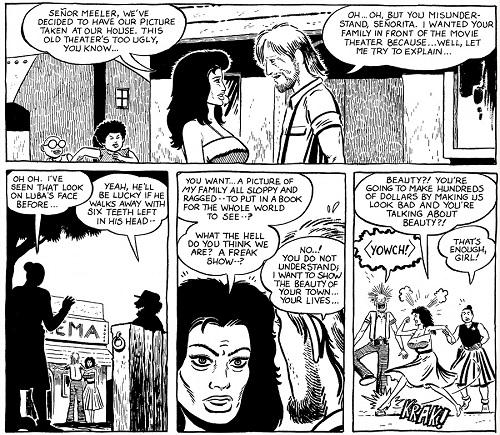

And the characters were any type of person we felt like expressing on the page, you know? It wasn’t what was expected. Like say a character like Luba, if she’s in a movie or a cartoon or whatever it is, that character’s usually a joke, right? You hire a gal that looks like that in a movie and it’s usually for the butt of a joke, that’s just the way society is. But you know, how about in Palomar, where she’s a person and she goes through everything a person goes through? I think that was new for people.

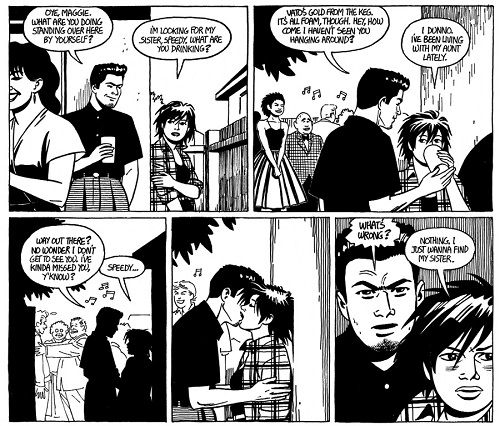

Jaime Hernandez: It felt special when my characters touched the ground. When I got ’em grounded, when I knew where they hung out. I knew who they were. I knew who belonged in what space. And I started to know my own characters better than ever. That’s when I kinda knew that it was gonna last. That was the important part for me, that I can do these characters, I can focus on different ones at different times, because I know them now. And that’s when I thought, “Okay, I got something here.” Hopefully for the reader, but definitely for myself.

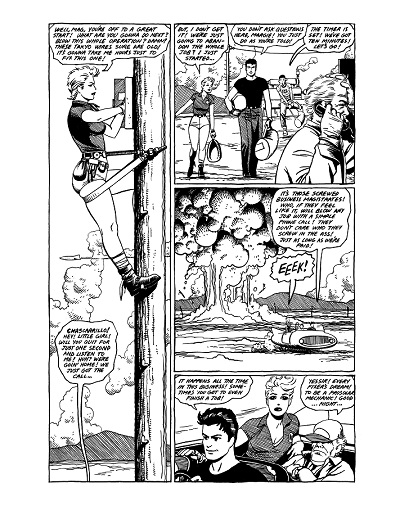

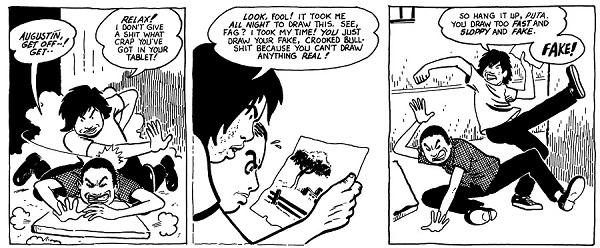

GH: What I think is really special about what Jaime did, is Jaime started out with a lot of detail, a lot of just, likability of looking at a comic book. He just had that going on, and it was science fiction-y and this and that, with light humor. What I think is remarkable is that he didn’t go that way, to be a big famous artist. He went inside to the characters and used that skill that could’ve worked at Marvel or wherever else if he wanted to. But what he did was he used that skill to tell human stories. And that’s something that was not encouraged in comics. To have Jaime’s skill to draw, you know, as well as he did, and use it for humanistic stories and not be, you know, whoever’s doing the new Spider-Man or whatever. I think that that took a lot of strength in a way that he may not have been aware of at the time.

JH: Yeah. It always seemed more important to me, like he said, to use my strengths to tell what I wanted to tell. I never thought of really using it for someone else, you know? It was always for me, like, “Oh, okay, I have this gift of drawing pretty well, so I get to draw what I want.” So it was always, for me, my stories. It’s something I had never really thought about, ‘til he brought that up. It’s almost like I didn’t know that “I coulda been somebody!” you know?

GH: But you would’ve been miserable though.

JH: Oh, I can imagine. Yeah.

FV: It’s a cliche to say it this way, but it’s very much, like “Don’t sell out,” right? We all wanna make some money, but both of you have been true to your artistic vision, for 40 years, you know, straight up doing what you want to do, no matter where that takes you. If that’s popular or not, you’re following your muse as it were, wherever it might go. To me that seems very connected with the DIY ethos, the artistic ethos, the punk ethos.

JH: And here’s another funny side note. The few times I did try to sell out to make money, they didn’t want me.

GH: Yeah. That’s the truth of it.

JH: I was like, “Oh, okay. When I’m outside of my Love & Rockets world, I’ll just be used for something.” You know, it’ll be, “Go over there and draw three straight lines,” and stuff like that.

And I go, “Oh, I thought you wanted my ‘genius!’” Apparently not, you know?

I remember trying to be like, “Oh, hey, uh, you know, I’d love to draw some record covers for you.” And they’d go, “Oh, yeah, no.” I mean, those were very humbling moments. At the same time, it was hard for me, and very uncomfortable for me to go outside of my personal space, my personal view. Every time I went back to Love & Rockets, it was home. And it was like “Okay, I know what I wanna do here and you’re gonna get the best of me,” you know?

GH: I had an acquaintance—who is no longer an acquaintance—but before Love & Rockets, I would draw, and it would look like a comic book. You know, It wasn’t a whole different style or anything, it was just what I learned in comics. And I imagine now that he was simply very jealous, and he said, “You know, you’ll never be good enough to sell out.”

FV: [Laughter]

GH: Yeah. And I looked at him like, “Okay,” you know, I let it go. And then I’m thinking “Yeah, it’s probably true,” because nothing I’ve ever done for Marvel or DC or anybody else has ever caught on, you know, I’ve done comics that I did my best on at different places, and they just didn’t catch on.

And Jaime is often looked at as an illustrator, outside of Love & Rockets. “Okay, let’s get this guy.” And then, like he said, “Oh, well we don’t want you.” I don’t know. There’s just a lot of small-minded nitwits out there that are running things and we gotta deal with it. And after a while you just stop and we just go back to Love & Rockets, our own thing. After a while we stop, you know, even bothering.

FV: Number one, tell it like it is! And number two, yes, that seems like a real core lesson that a lot of young creators should learn at some point. You know, like it’s okay to do other stuff, we gotta pay the bills. But then also you have to own your own thing, right? You’ve got to have something that you can always come back to that’s yours, and Love & Rockets is yours. It’s gonna be with you forever, right?

GH: Yeah. That’s us. It’s what we’re proud of. It’s what we are, who we are. Warts and all.

FV: When someone first introduced me to Love & Rockets, they just handed me an issue and I just dove into the middle of the story, and I had no idea what was going on. Now comics have gone through such a shift to the graphic novel format, something with a beginning, middle, and an end. It’s a challenge to come into Love & Rockets for new readers in some ways. Do either of you have a story you like people to start in on?

GH: For me, it’s the first “Palomar” story, Heartbreak Soup. Just start from there. That’s where I’d say. But that’s, you know, that’s a lot of years of comics, man! I dunno.

JH: I guess I would say start with Death of Speedy, cuz it’s old, but it still holds up for me. But personally I would just say follow the girls. You know, Maggie and Hopey, find them because hopefully they’re gonna grow on you and you’re gonna want to find out where they are later.

FV: I think that there’s something special too about what you were saying, just like following the girls, right? Follow the characters. If you dig it, see where it takes you. There’s something kind of magical about it, less prescribed and like restricted in some ways.

JH: Yeah, and hopefully you’ll wanna go back, you know, wherever you find them, if you like ’em enough, you’re gonna wanna go back and find more. I know that for a lot of people, that’s work!

GH: The thing is with Jaime’s work, especially once you get to a good page of Maggie and Hopey talking, the reader’s there. I think the potential reader is now interested, if there’s a good page of them talking and just, you know, Hopey is goofing around with Maggie and Maggie’s not sure how to react. It’s pretty quick. Cause I remember early on when we first started showing people the comic, it was instant with Maggie, in the beginning, with “Mechanics,” the first story: Maggie’s getting up out of bed, she doesn’t wanna go to work, and Hopey’s talking.

And I remember lots of readers, especially women, would just say, “Oh, this is about me. This is me.” And it was only the first page of the story! So I just figure, whenever they fall into the right page of Maggie and Hopey hanging out, I think they’re hooked. I think they’ll look for more, cause you won’t find it anywhere else in comics.

JH: Follow the girls.

FV: I was reading in a recent issue of L&R, and Gilbert you had a page where the characters were at a comic book show, and one of them is looking at “Lovers & Rockers,” a fictitious version of your thing, and he says something like, “I can’t believe these guys haven’t been canceled yet.”

GH: That was just a gag. Cause you know, we’ll turn people on to Love & Rockets, or the documentary will say, “You gotta read this comic.” Well, luckily the documentary showed that some of it’s a little racy. Pinup-y type art, you know? And that’s not what people are looking for normally, when they’re looking for the next comic they wanna read, they’re like, “Well, this is serious. This is about culture, this is about feminism, this is about gays and, you know, downtrodden people, and all kinds of different people.” And then they come and they see these pinup girls, you know? So I always figure that one of these days, they’re gonna go, “I read Love & Rockets and it was just pinup girls,” you know? A lot of people just see one thing, they’ll just see the pinup girls, but they won’t read the rest, they won’t see the humanity and the rest of it.

They’ll just have their prejudice and they’ll bring it along and they’ll, you know, say “That’s it, that’s what this is about.” We’ve had arguments like that and it’s silly because the person just doesn’t feel comfortable looking at that kind of art, you know? Okay, fine.

But if we’re gonna fight body shaming, you have to accept both. You have to accept the people that are unpleasant looking, and you have to accept the people that everybody else really likes, you know. That exists on our planet and that’s what exists in Love & Rockets. So it does make it difficult, I’m sure, for readers looking for the right tone, for the work to speak for them. I go, “Well, Love & Rockets can only help you part of the way.”

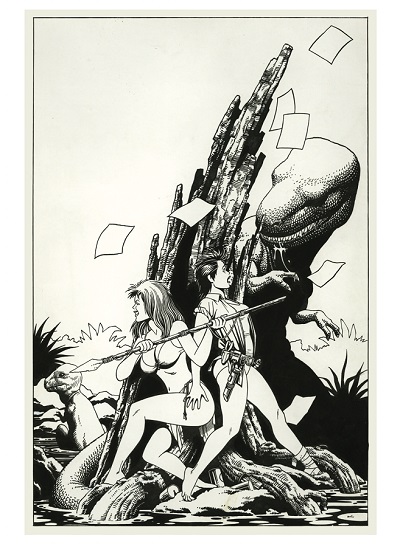

JH: I got a letter from a woman who said that one day she walked into a comic shop and she saw a cover with two scantily clad women being chased by a dinosaur. That was the second issue of Love & Rockets. She said, “I cannot believe what I’m seeing here. Oh my God!” And she put it back and she left. But something made her come back. “What’s different here?” You know, she was sensing something different. And then she became a fan, and I was just like, “Oh, phew!” You know, wipe my forehead!

GH: Just recently I was talking to an ex-girlfriend who was looking at Love & Rockets, and she goes, “Oh, this is just about girls in their underwear,” right? I go, “Really? In 40 years of these comics, that’s all there is in this book?” People bring their baggage, you know, they bring their prejudices and baggage. Really, with all the super violence in our comics, and in other comics, and everywhere else, and all this horrible stuff happening to people all the time, girls in their underwear are the problem. So that’s when we start dismissing some criticisms.

But it’s a new generation, and they look at that cover of Maggie with a dinosaur and Penny Century and they go, “That’s awesome.” We hear young people saying, “That’s awesome. I like that.” Like how women are seeing more female superheroes in movies and they like ‘em. They’re dressed in tights and they’re blowing up stuff and flying around. Good! Just show them doing cool stuff. Cause a lot of the prejudice comes from old comics and entertainment where that type of person is victimized in the story. You know, like Maggie looks like a victim maybe to certain people. But then you see her adventure inside. I guess we just have to keep pushing back the old, stuffy, conservative thinkers. Get ’em away from us. Away, away!

FV: I mean, that’s something about comics too, right? Because they’re so visual, people think they can “get it” at first glance. As if they can look at the cover and they can understand it. I think that that speaks to something that’s unusual about both of your works. Gilbert, you said “Oh, do you really think that for 40 years it’s just girls in their underwear?” But it’s true that for a lot of comics in the past, really it would have been just 40 years of girls in their underwear, and that’s it. It’s that you guys have somehow injected that humanity that you’re talking about, it expands the ideas. You get to know the characters, and so you get to know that they’re more three-dimensional.

Photograph by Morgan Pierre Photography

FV: So you guys are still doing new stories, stories that are connected with Palomar and with Hoppers, but moving in new directions. What inspires you to keep going?

JH: For me, I just wanna see what happens, where the characters are going. My own characters, and Gilbert’s, too. I wanna see how it turns out at the end. I’m waiting for the last panel to say “The End.”

GH: Yeah. We have no idea. Okay, here I go, going grim here. But nobody knows their own death. It’s the same thing with the end of Love & Rockets. We don’t know how that’s gonna end. What the last drawing, what the last line on it is. There’s gonna be one. But we don’t know. We don’t, so we keep it open and that makes us happy. You just keep it open until it gets there.

JH: And that’s what keeps me interested, like “Okay, how are you gonna wrap this up?” And I’m talking to myself!

GH: You know, we don’t really know. And the openness of not knowing is what’s helped us over the years. We never learned that we shouldn’t be doing this. We never learned that this wasn’t gonna make us rich or super famous, like a superhero comic or something. That doesn’t matter anymore. You think about it when you’re young, but now it’s like, “No, we’ve done it.” We’re here and we have enough intelligent readers telling us over 40 years how much they like the comic. So we’re not gonna, we’re not gonna turn our back on that. We’re gonna take that to heart.

Buy Love and Rockets: The First Fifty online here

Interview by François Vigneault

[…] Los Bros Hernandez interviewed on Broken Frontier.https://www.brokenfrontier.com/jaime-gilbert-hernandez-love-rockets-fantagraphics-first-fifty/ […]