One of the most potent reasons for an artist to couch their story within ancient archetypes is to tap into more universal human concerns rather than the specific issues of the present day. In My Dead Mother, Clara Jetsmark uses the veneer of a tropical mythology to examine the complex relationships women have with their mothers, with men, and with each other. Like all fables, My Dead Mother is trying to communicate a moral to the reader; one regarding the diametrically different roles offered to women as either mother or spinster. Yet Jetsmark chooses to portray neither role in a conservative manner and gives all of her characters a modern sensibility as well as a modern cadence. This results in a work that joyfully revels in its inspirations, both in Jetsmark’s clever re-imagining and re-contextualization of a magical realist world and her ability to depict it with flourish and aplomb.

The story of My Dead Mother follows two young women – the studious Monga and hunk-obsessed Kitty – on a journey to break the curse afflicting Monga (the still living but disembodied head of her mother wrapped like a ghoulish mummy and bound to Monga’s own). Fed up with the mother’s frequent ghostly wailing interrupting their studying and flirting with boys, the pair ask the giant-headed Loa to break the curse. Per his role as a shaman, the Loa agrees to help them (though only after being smitten with Kitty) and sends them on a quest into the mountains to recover an herb needed to complete the ritual to free Monga’s mother.

The story of My Dead Mother follows two young women – the studious Monga and hunk-obsessed Kitty – on a journey to break the curse afflicting Monga (the still living but disembodied head of her mother wrapped like a ghoulish mummy and bound to Monga’s own). Fed up with the mother’s frequent ghostly wailing interrupting their studying and flirting with boys, the pair ask the giant-headed Loa to break the curse. Per his role as a shaman, the Loa agrees to help them (though only after being smitten with Kitty) and sends them on a quest into the mountains to recover an herb needed to complete the ritual to free Monga’s mother.

Their quest is uneventful but long enough to give the insecure Loa time to lift weights until his freakishly large arms match his enormous head. After another failed ritual, Monga is still stuck with her mother’s head still alive and still attached to her own, while Kitty has found the hunk she has been seeking in the form of the Loa. Stamping off into the jungle, Monga has her mother’s head torn away by a leopard that fortunately turns out to be her mother’s freed spirit consuming her former physical form to become whole again. Their roles now reversed, Monga’s leopard mother carries her lost daughter back to the village in time for her to take exam she has been trying to study for this whole time.

While the plot is light, it is how the characters exist within it that gives My Dead Mother its charm. From the beginning we see Monga and Kitty fighting over how to secure their futures, whether to study or to rely on a man. The reader quickly recognizes Jetsmark’s ear for dialogue by her giving both protagonists (as well as all the supporting characters) “Smart Alec” voices, reminiscent of Kate Beaton’s subversion with historical figures. Jetsmark plays the ditzy Kitty off against the overly serious Monga with the two women being near identical in appearance so as to highlight the divide between them, yet neither is played as superior to the other.

Monga needs to be pushed out of her pessimism and begrudging acceptance of the curse upon her by Kitty’s excitement to see the Loa. Kitty is also the one who sways the Loa into helping them after lying about having lost the required sacrifice. Though it is Monga’s strength in bearing the ghostly head of her mother all the way through to the completion of the ritual that allows for the final triumph to be achieved.

This motif of who carries whom is central to the deeper themes of the work. While the primary image is of Monga carrying her mother on her head, early on her mother mentions having carried Monga on her back over streams for years. This is then referenced again during the ritual with the Loa when in Monga’s visions she sees a skull-faced leopard (representing her mother) carrying a baby on its head, wrapped much like the mother’s head has been up to this point. The manifested leopard mother will later carry her daughter on her back again, but this is not the final image of a child being carried. That is reserved for the book’s closing image, one of a scroll carrying Monga placed opposite the baby-carrying Kitty.

This carrying of others is then less the curse it initially seems. Monga’s mother carrying her gets her both metaphorically and literally to the place where she can pursue her path as a scholar. Monga carrying her infirm mother in return is recognition of this sacrifice. While Monga ends the cycle of mothers and daughters carrying one another, Kitty will continue it. Though the two are on opposite paths, both are valid, both are equal.

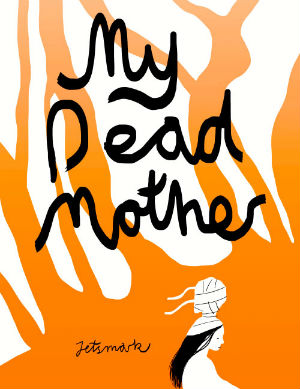

This collage of folklore, sharp-tongued comedy, and feminist subtext is nicely brought together by Jetsmark’s skill as a cartoonist. The book itself is riso-printed but eschews the typical neon colors of that printing process in favor of a mix of deep black and creamsicle orange. It gives the work a light-hearted feel in keeping with the tone, with many of the panels neatly balanced by large swathes of orange. Her panels are light on detail but strong in composition, frequently pulling the camera back enough to show the vast natural world around the characters.

This collage of folklore, sharp-tongued comedy, and feminist subtext is nicely brought together by Jetsmark’s skill as a cartoonist. The book itself is riso-printed but eschews the typical neon colors of that printing process in favor of a mix of deep black and creamsicle orange. It gives the work a light-hearted feel in keeping with the tone, with many of the panels neatly balanced by large swathes of orange. Her panels are light on detail but strong in composition, frequently pulling the camera back enough to show the vast natural world around the characters.

In an interesting aesthetic choice, the foliage is often rendered entirely in black or bent at canted angles. It adds an air of otherworldliness that presages the supernatural turn the story will take. Jetsmark’s characters have simple expressive faces that perfectly capture the performance of the dialogue; their body language revealing what petty, anxious, frustrated, and ridiculous characters they all are. The final sequence of Monga astride her tiger mother bounding into the village is especially striking in Jetsmark’s ability to render action and velocity.

My Dead Mother is a strong debut comic for Jetsmark. She sets out to tackle a lot and manages to do so with ease. It is a work that functions well from surface level all the way down to its depths, with multiple re-readings revealing many subtle details. Even in as slight a document as this, Jetsmark impresses with her control of all aspects of her visual storytelling.

Clara Jetsmark (W/A) • Uncivilized Books, $6.00

Review by Robin Enrico