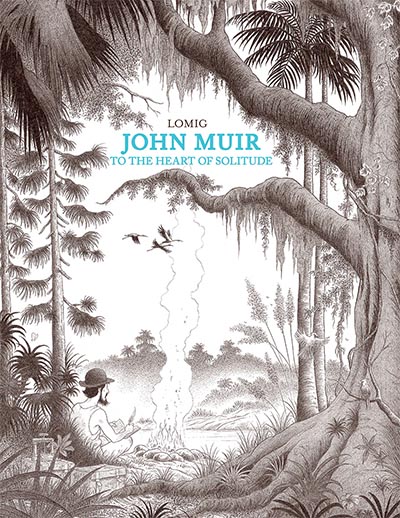

It has long turned into a cliché: our collective need to hail books about the environment or environmentalism as timely or relevant. It is a cliché because, despite how good or bad the books themselves may be, the issue has never really been outdated. It was around even as Thoreau wrote Walden, while worrying about the encroaching sound of locomotives in his backyard. And so, with that disclaimer, one must reiterate that John Muir: To the Heart of Solitude, by French artist Lomig, is timely, relevant, and important.

Biographies, by their nature, are evaluated by how interesting their subjects are. By that measure, Muir has a lot going for him, given that his legacy as America’s Father of the National Parks continues to shape policy while impacting the lives of millions. Without him there would be no Sierra Club which, since 1892, has lobbied for policies that promote sustainable energy and mitigate global warming. It continues to spread the word wherever it has members. In the month of this book’s publication, for example, the Club’s Wisconsin Chapter Wildlife Team hosted a variety of activities to help bring awareness to the ecological benefits provided by beavers on the landscape.

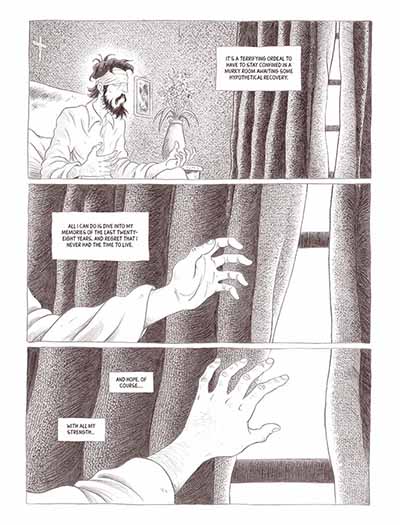

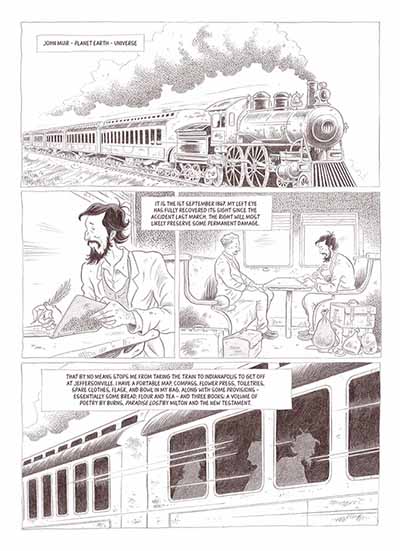

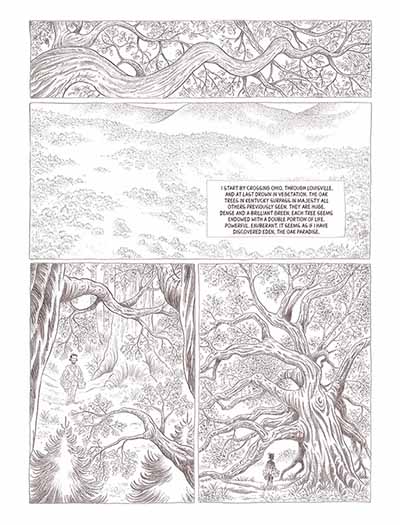

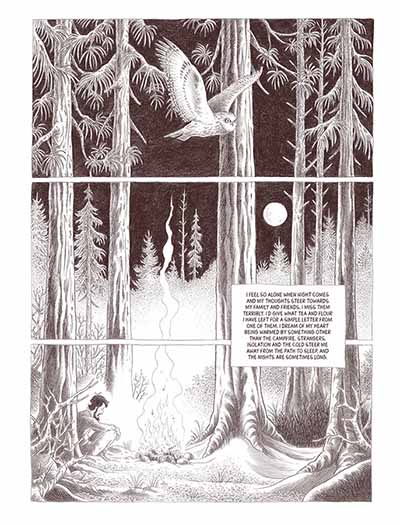

Then there’s Muir’s story itself, a wondrous journey of belief in the power of nature that began with a life-changing accident. It occurred when he was 29, and when the threat of losing his sight forever pushed him into embracing a long-held dream of exploring the wild. Lomig focuses on that first trip, using his now celebrated dual-toned style to recreate a wild America that no longer exists. There are sweeping vistas documented in these pages, along with close-ups of flowers, and panels peopled by simple folk who worked the land.

One of the nicest things about NBM is how they allow subject to determine style; it’s why this large format can do justice to Lomig’s delicate portrait of a country and its people. The question posed at the beginning — of what drove Muir to becoming the environmentalist figurehead he did — is answered not merely through facts or figures, but through this patient depiction of landscapes that shaped every aspect of his character.

The words here come mostly from Muir himself or, in some instances, from people who were inspired by his lifelong commitment. They chronicle the trials he faced on a first trek to Florida, followed by a thwarted trip to South America. “The mountain is inside me,” Muir writes, ‘”n each of my nerves, penetrating every pore. I vibrate with the wind and the trees, the water and the rock, the earth, the sky and the sun’s rays.”

Earlier this year, a groundbreaking study by UMass Chan Medical School revealed that interacting with wildlife could help ease PTSD symptoms. It observed that activities such as forest walks and birdwatching had notable psychological benefits, and reduced anxiety. The need to protect what is left is more critical than ever, seeing how environmental challenges only appear to increase. To that end, a biography that can introduce new audiences to the power of Muir’s simple message is more than welcome.

Lomig (W/A) • NBM Publishing, $24.99

Review by Lindsay Pereira