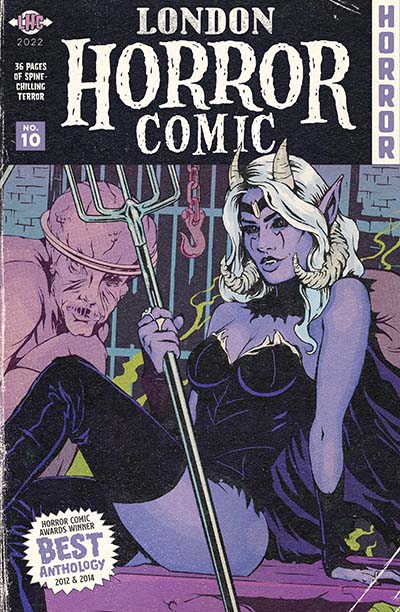

If you’ve been attending UK comics festivals and cons to any degree in the last 15 years it’s very unlikely that you haven’t at some point encountered British small press fixture John-Paul Kamath. He’s an always welcoming presence and his London Horror Comic must surely be the longest self-published genre comics project currently still in publication. After over a decade and a half of unsettling horror hijinks LHC recently reached its landmark tenth issue. A fitting point, then, at which to catch up with JP to ask him about his particular approach to horror, how the scene has evolved in that time, and his plans for the future…

ANDY OLIVER: London Horror Comic has just hit its landmark tenth issue so let’s start by asking about the origins of the book and why the genre holds such appeal to you?

JOHN-PAUL KAMATH: I was a regular writer for a Previews-listed US-horror anthology back in 2003. Standard fare: a Tales From the Crypt twist-at-the-end vibe. It was great for honing my craft and getting to grips with things like structure and pacing. But I noticed that the stories I was writing were becoming formulaic. That’s always a danger with writing for any publisher other than yourself that you don’t get better as a writer, you just get better at giving a publisher what they want. Don’t confuse the two.

This all lead to me submitting a story that got rejected; the editor said it was creepy but not for them. It was my first eye-opener into the paradoxes of mainstream comics publishing – offbeat stories aren’t sometimes published because they’re bad, but because they don’t fit with a pre-existing spectrum of expectations or easily identifiable customers.

Which I found weird, because at the same time in my life I was visiting the Fright Fest Film Festival in London, where the sheer variety of horror films demonstrated the places and imaginative rendering the horror genre could take subjects to in films – so I thought, why not in comics?

Art by Ben Newman

I took the script for my rejected story and paid a mate to draw it and stuck it up online as a free PDF.

I got a lot of positive feedback from a bunch of people who wanted to see more. This was a real moment of encouragement. I suddenly thought I might be able to produce a book in my own way that people would really dig. The web as it was at the time played a key part – if my belief hadn’t been pre-validated in some way I don’t know if I would have taken the jump into the full self-publishing venture.

Looking back, I’m glad I did. I honestly thought I’d just do one issue just so that I would have a physical object to look back on when I was old and grey. I honestly didn’t think I’d be here 10 issues and seventeen years later but somehow I managed to outlast DC’s New 52 at least!

AO: What have been some of the storytelling highlights of London Horror Comic for you over these last ten issues? Which stories are you particularly proud of?

KAMATH: I’m proud each issue of London Horror Comic has maintained its variety and remains off-beat in contrast to mainstream horror comics. It can be very tempting to start out with a noble small-press publishing vision but to have it morph into something indistinguishable to its mainstream counterpoints – if only for the reason of selling to a more easily identifiable audience.

I’ll never forget a first review of issue 1 which had four stories in it which I found online written by a blogger. The reviewer said something along the lines of: “This comic has four stories. Three of them are shit but the fourth is the best horror story I’ve ever read in comics.”

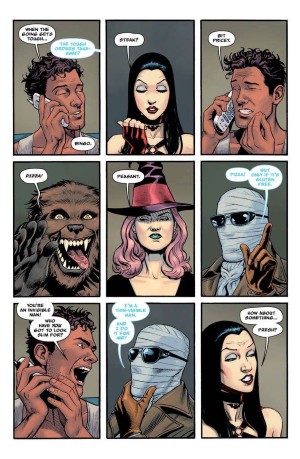

Art by Flops Comics

It made me chuckle not least because I put the same thinking behind all stories I write, but that depending on the disposition that a reader has towards what a horror story should be (funny, scary, etc.), it is that disposition which can ultimately determine how the story is received.

I can’t tell you the amount of times I’ve waved down passers by at a convention who’ve I’ve spotted with a slab of newly bought Walking Dead books asking them if they’d be interested in cracking the spine of my book to which they’ve replied, “Sorry, I don’t like horror!” That’s because to them The Walking Dead has transcended their predispositions about what horror is or isn’t. And so to live in a niche where there are as many people that are keen to see your take on horror as those that dismiss it outright as beneath them, well, it’s an exciting place to be!

AO: What can readers expect to see in the new issue of London Horror Comic?

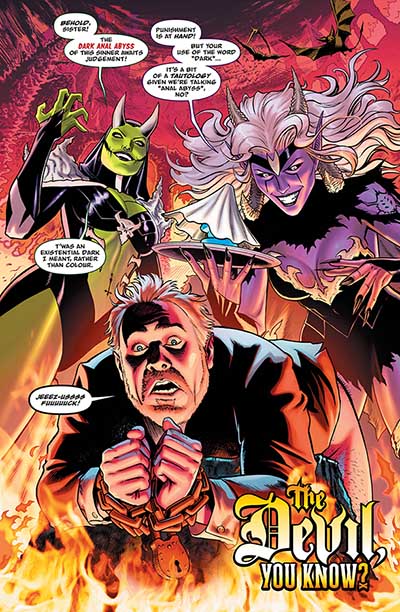

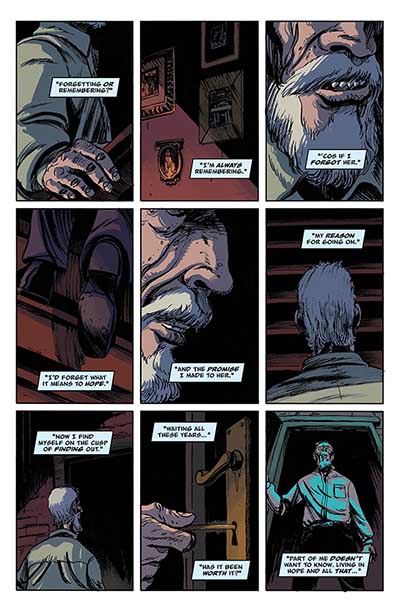

KAMATH: Well, we have two stories. The first breaks new ground for me as it’s a three-partner continued across the next two issues. I’ve never done a to-be-continued story before as when you work in small press you’re not guaranteed a next issue, but after ten issues I reckon I’ve got grounds to be confident! It’s my first attempt at building a world and the art is by Craig Cermak who is brilliant at making faces distinct and nailing the comedic body language – even in a supernatural context. The second story is a stark contrast in that it deals with the horrors of holding out for hope. Gustaffo Vargas lends a emotional heavyweight pacing to a two-people-in-a-room style story.

Art by Craig Cermak and Hi-Fi Design

AO: Can you tell us a little about some of your artistic collaborators and what they’ve brought to the series over the years?

KAMATH: All my collaborations have been virtual and yet the final art always seems to succeed better than I imagined. At times I wonder whether the secret of a successful writer-artist collaboration is being part psychic on both parts.

That said, each artist has brought something unique. Lee Ferguson, a mainstream US comics artist, was able to bring a European-style minimalist approach to many of the early stories. His choice of how to render just enough so as to leave things to the reader’s imagination, gave those earlier stories a punch. Dean Kotz, another early collaborator, is an exceptional draftsman. The sense of distinct characters living in a defined space is key in making short stories land with the reader. My more recent work with Craig Cermak and some of the more humorous stories have been blessed by Craig’s gift for body language and expressions.

I’ve come to realise that every story has a natural visual leaning, something which takes the script beyond its original ambition to reach that elusive point known as art. It can be unconscious to me as a writer as I’m typing the thing, but it is there, in everyone’s script and if you find an artist who can bring those highlights out, that’s when a story can really sing.

Art by Craig Cermak from London Horror Comic #8

AO: In terms of curation how do you go about that in terms of that collaborative process? Are you writing with a particular artist’s style in mind? Or do you look to match suitable artists to story after the writing?

KAMATH: Setting out a clear and easy to understand script for the artist to read and draw is my first role. That might sound obvious to the point of redundancy but the script itself must be readable, beyond the worth of the story it’s telling. If it’s a pain to read the script, then it’s going to feel like a slog for the artist to get fired up about – a bit like giving someone a phonebook to read and saying; now draw me a crowd of hundred faces!

I’ve learned over the years; the script itself must inspire a vision in the artist as to what end effect the story should have on the reader. Rather than say, for example, writing an instruction for an artist to create a sense of dread in the drawing, it’s the task of the writer to bring out that sense of dread within the script. I find myself humming a tune when it comes to script-writing, and if the artist catches it and can begin riffing with it, that’s the seed from which something better than the sum of its parts emerges from.

The first reader the story ultimately must have an impact on is the artist and so I angle my scripts just so that it inspires the right kind of magic.

Over time, I’ve got into a groove where I establish the basics of the story and then re-write it to emphasise the strengths of the artist I eventually work with and this seems to work pretty well.

AO: You’ve been self-publishing since some time around the mid-2000s. How has the UK indie scene changed in that time? How has it developed for the better and, conversely, what are the most notable challenges still facing small pressers?

The sheer volume of UK indie comics is now larger and more consistent in a way that justifies it being called a “a small press scene.” I might sound like an old man saying this, but these kids today don’t know how good they’ve got it!

We’re lucky we have consistent known creators putting out work regularly to audiences they have built and an audience who acknowledge a wider small press scene. Before foraying into UK small press myself, discovering new small press work and work of quality was hard and cumbersome to come by. It’s a stark contrast. Equally, the mainstream US comics market has become typified by variant covers and a niche speculation market rather than the quality of story content. If you like comics and are interested in the stories comics can tell then there’s never been a better time to immerse yourself in the UK small press scene.

Are far as challenges go, centralised distribution that’s sensibly capitalised and which has got an eye for promotion both inside and outside comic stores is a bit of a wish. The more small-press works that can be discovered at more places in volume, the more seriously the scene will be taken as a creative force which is home to some fantastic talent.

Equally, the breadth of coverage about the quality of talent brewing under the UK’s own cultural nose through the works of UK small press creators is still lacking. Thank god for your good self and Broken Frontier for flying the flag for all these years!

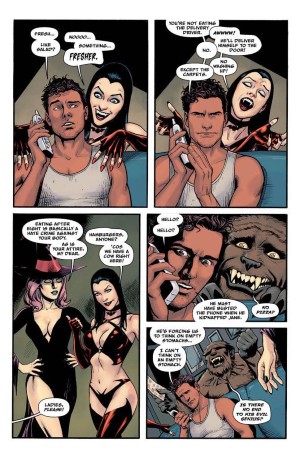

Art by Craig Cermak and Hi-Fi Design

AO What are some of the freedoms that self-publishing brings to the creative process?

KAMATH: Paradoxically, the freedom to print whatever I want places more of a burden on me personally when deciding how far to go. There’s a lot of empty-headed material out there and that’s never been my aspiration for the book. I’d like to think London Horror Comic has a dichotomous identity: it may appear, at a surface level, something conventional, but reading between the lines people hopefully get how it’s subverting things with the genre.

On the flip side, I’ve spoken to other creators that do horror or comics with adult themes, and there is a trend of people actively self-censoring what they feel they can write or draw, based on how people may react or misunderstand their intent. That’s why I think a lot of so-called horror books are anything but unsettling.

With horror, you’re always walking a fine line between telling stories that give air to the unsettling, which provoke a response, but I feel a creator should have a goal beyond just wanting to push people’s buttons.

Art by Gustaffo Vargas

AO: I always think of you and Douglas Noble as being two of the most notable creators at conventions/festivals when it comes to engaging with your audiences in public. What lessons have you learnt over the years about raising your profile and bringing in new readers?

KAMATH: I think the first big lesson I learnt from engaging with the public at conventions is that there are more people willing and wanting to discover new non-superhero non-mainstream work than those that don’t, even though at the start it can feel like quite the opposite.

I found some thinking which helped me overcome my hesitancy in getting my name out there in a book I read once called The Art of Film, and right at the beginning the writer described the three stages of making a film. The first was the filmmaker’s unique point of view or take on the world which serves as inspiration. The second was fashioning that point of view using the tools of the medium to create an effect. And the third was presenting that work to an audience to observe the recognition of its effect and the kindling of the filmmaker’s point of view.

In that sense, a work of comic art for me isn’t complete when it’s printed, it’s completed once its in the hands of a reader. So, if you see selling your book as achieving that final step in the artistic process, it can help you get over that hump you may have as a creator in extending a hand out to the world and inviting them to take a look at your book.

Happy punters!

AO: You’ve taken sidesteps into satellite projects to LHC like the Graveyard Orbit series. Do you have any yearnings to tackle more genres outside of the horror arena?

KAMATH: I’m gripped by moments of inspiration where I needed a vehicle other than horror to tell the story I needed to, hence the spin-off non-horror titles like Graveyard Orbit. However, I think my writing’s reached a place where even though a story might be a horror at its core, I’m able to bring other genres and contrast. This is because I guess life is a rollercoaster of several different genres at once, and so I might as well reflect that aspect in the horror stories I write.

AO: And, finally, what’s next for JP Kamath and LHC?

KAMATH: I’ve had a mantra that I’ve recited since I began this 17 years ago and that’s “Just one more issue.” Those four simple words have kept me grounded and focused and to be honest, all I ever want to do is just one more comic. No Netflix contracts. No animation deals. Just making the one more comic and making it the best version of the story I have to tell. As I said earlier, the small press scene can be a fickle place and you’re not promised tomorrow, so enjoy whatever you’re working on now and get it out there.

Buy London Horror Comic from John-Paul Kamath online here

Interview by Andy Oliver