BROKEN FRONTIER AWARDS – BEST COLLECTION OF CLASSIC MATERIAL WINNER!

Having gained the rights to a host of Brit weekly comics of yesteryear, 2017 saw 2000 AD publisher Rebellion release a number of eagerly awaited retro comics properties as part of their new Treasury of British Comics line of books. From 1970s/’80s supernatural strips from Misty and Scream! to the adventures of suburban super-hero The Leopard of Lime Street through to a long-awaited compilation of Ken Reid’s humorously grotesque Faceache, it was a feast of nostalgia for old-time readers and a chance to be introduced to some of the very best comics the UK has ever produced for newer ones.

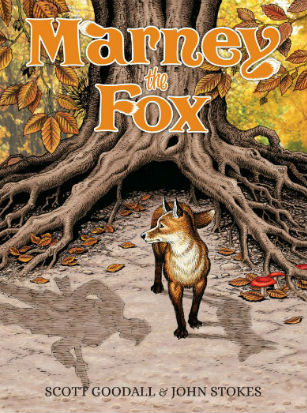

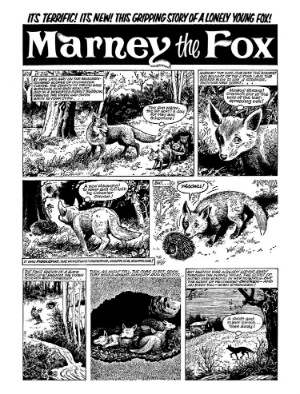

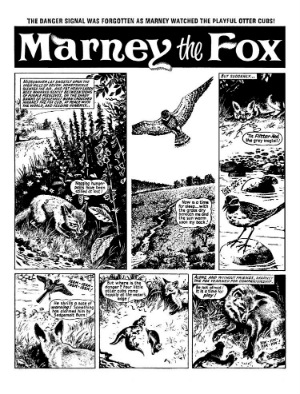

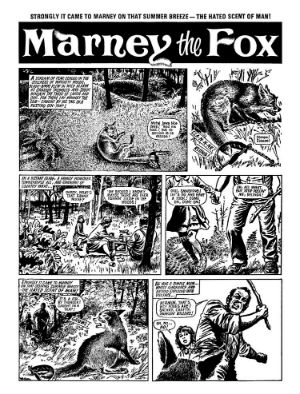

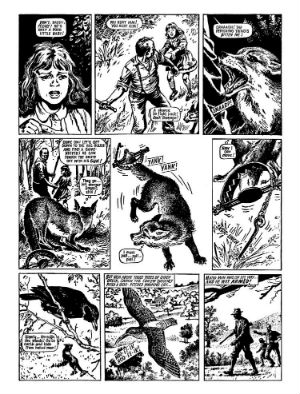

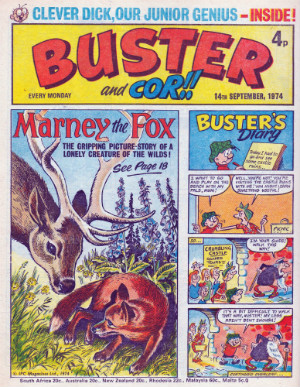

All of these collections have been positively received but one in particular stood out as truly special. Marney the Fox – Scott Goodall and John Stokes’s 1970s serial from the pages of weekly anthology comic Buster – follows the adventures of an orphaned fox cub as he journeys across both the seasons and the Devon countryside, frequently facing the threat of “hated man”, predatory wildlife and natural disasters. It had been, arguably, a neglected classic in the Brit comics pantheon and its recent publication in a handsome hardcover edition has underlined its place as one of the true masterpieces of children’s comics. That was recognised this year when Marney the Fox (reviewed here at BF) was voted by the Broken Frontier audience and team as Best Collection of Classic Material in the 2017 Broken Frontier Awards.

All of these collections have been positively received but one in particular stood out as truly special. Marney the Fox – Scott Goodall and John Stokes’s 1970s serial from the pages of weekly anthology comic Buster – follows the adventures of an orphaned fox cub as he journeys across both the seasons and the Devon countryside, frequently facing the threat of “hated man”, predatory wildlife and natural disasters. It had been, arguably, a neglected classic in the Brit comics pantheon and its recent publication in a handsome hardcover edition has underlined its place as one of the true masterpieces of children’s comics. That was recognised this year when Marney the Fox (reviewed here at BF) was voted by the Broken Frontier audience and team as Best Collection of Classic Material in the 2017 Broken Frontier Awards.

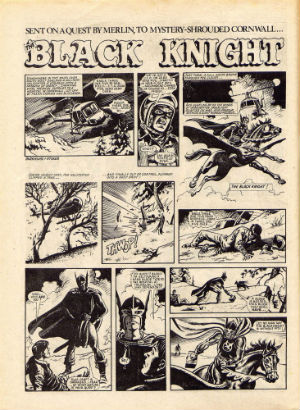

At the tail end of last year I had the true privilege of chairing a panel conversation with Marney the Fox artist John Stokes at London’s Gosh! Comics (above right), alongside Rebellion’s Ben Smith. John was in fine form, regaling us with anecdotes about a career that began in the 1960s and took in not just British serial comics characters but also a memorable run on The Black Knight in Hulk Weekly, L.E.G.I.O.N. and The Invisibles at DC, and licensed properties like Doctor Who and Star Wars. His work was most recently seen in last year’s Scream! and Misty Special.

John and I recently revisited some of that Gosh! discussion by e-mail. We’re delighted today to celebrate that BF Award win for Marney with this comprehensive chat with the great man himself (which includes some seldom seen art provided by John).

ANDY OLIVER: To begin could we start with your very earliest comics memories? What were the first comics you discovered and that particularly inspired you?

ANDY OLIVER: To begin could we start with your very earliest comics memories? What were the first comics you discovered and that particularly inspired you?

JOHN STOKES: Until the age of eight I hadn’t, to my knowledge, set eyes on a comic. I had spent my childhood in India, where my father was an officer in the Royal Indian Army, mostly in garrisons on the North West Frontier or in the foothills of the Himalayas, postings too far off the beaten track for any comics to venture.

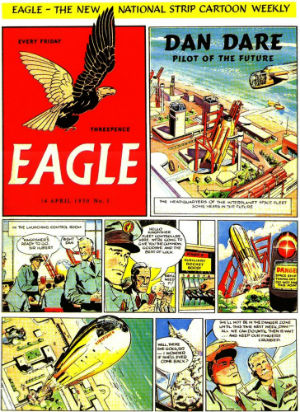

It wasn’t until I came to England that I was given my first comic, and the one that made the greatest impression was the first edition of The Eagle (left, art by Frank Hampson). I can still picture the cover with that gloriously phallic 1950s spaceship rising from the launchpad!

I was hooked from that moment, and my heroes were Frank Hampson, John Worsley and all the other great Eagle artists.

You first started working in comics in the early ‘60s. What was your entry route into the industry? And what were some of the earliest strips you worked on at IPC?

I was introduced into the comics industry by my brother George. He was four years older than me, and while I went to art school he was taken on by a Graphics Studio, opposite Foyles bookshop, in London. By some quirk in the education system I was admitted to Guildford Art School when I was only thirteen! My greatest influence in the three years I was a student there was learning lithography and etching by Nigel Lambourne and Ian Ribbons, both well known illustrators of Folio books, and it was there that I was introduced to Theatre Design, my other lifelong career. I went on to take my degree in theatre design at Wimbledon School of Art and enrol for a post-graduate year at the Slade School of Fine Art.

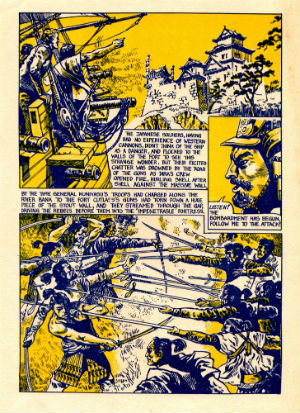

When I graduated I found work painting scenery on the Old Vic’s paint frame for a five figure salary (Five pounds, twelve shillings and tenpence a week! ). So when George, who was working for Fleetway publications at the time, and was being offered comic work that he was too busy to do, put me forward to take on the stories I jumped at the chance. I first worked for a small publisher called Atlas Publishing and Distribution Company, in Bride Lane, off Fleet Street, in a building which is no longer there, before moving on to Fleetway’s War Library titles, and then on to a weekly strip called Crisis Carson before taking over from the great Geoff Campion on a story called Britain in Chains and its sequel, The Battle for Liverpool in the Lion.

Marking a comics career spanning nearly six decades – ‘Dirk Cutlass’, one of John’s very first commissions from Atlas Comics circa 1960/61 and his 2017 cover to Rebellion’s Marney the Fox collection

How would you sum up the premise of Marney the Fox and the strip’s spirit in terms of its themes, where it took its inspiration from and writer Scott Goodall’s vision for the character?

Scott’s vision for the story was to feature an animal protagonist, very much in the style of Williamson’s Tarka the Otter ( even their names are strikingly similar – Marney’s name means ‘Little wandering one’ and Tarka’s ‘wandering as water’). As in Henry Williamson’s book the landscape of Devon features strongly and the passing of the seasons are integral to the narrative. The script became a love-letter to his adopted County and a young creature living wild and free. We never had the opportunity to speak to each other, but in an interview Scott said his thought was to do a ‘boy alone against authority’ series, but to make it an animal hero.

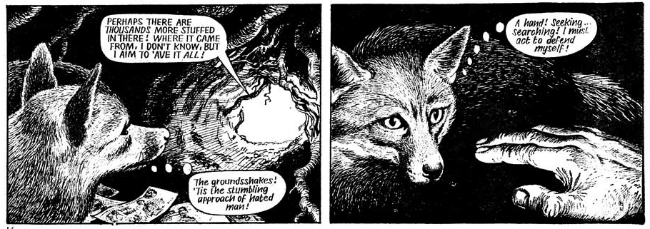

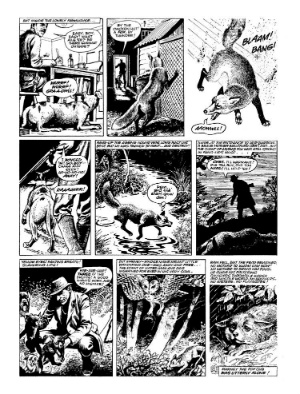

At first he instructed me in the script to make every picture as seen through the eyes of the animal alone, and that all humans should only be seen from the waist down, but he must have abandoned that idea almost immediately, as frame two of page one calls for a close up of Marney, and most of the first episode follows his mother on her last hunt, which he couldn’t possibly have seen. I must admit that I can’t imagine the story without the many close-ups that lead us into a feeling of empathy with the young fox.

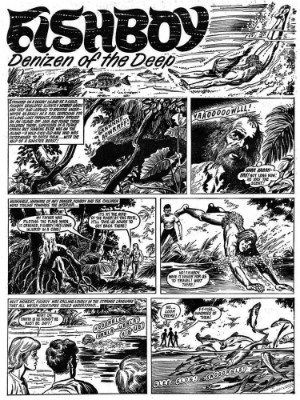

The two of you also worked on the short-lived The War Children and the long-running Fishboy in Buster. Your collaborations with Scott Goodall were certainly eclectic. Can you tell us a little bit about those two other Goodall/Stokes strips?

The two of you also worked on the short-lived The War Children and the long-running Fishboy in Buster. Your collaborations with Scott Goodall were certainly eclectic. Can you tell us a little bit about those two other Goodall/Stokes strips?

Fishboy was an absolute marathon, 360 instalments, all drawn by me. It was the story of a boy, lost at sea and surviving as a feral child, living in the ocean and learning to converse with sea creatures. Although artists and writers were never credited in those days Scott craftily slipped in a name check for us in the final episode when Fishboy asks his parents what his real name is. His father replies ‘it’s Marcus Scott Goodall John Stokes Lawrence’, to which Fishboy replies ‘By the cough of the Chinese carp! That a long and funny name! Me prefer Fishboy’. So, Scott and I have the dubious honour of being the first writer/artist team to get a credit in an IPC publication!

Looking at the three stories as an arc, we have a feral child surviving in the sea, followed by a feral fox surviving in a hostile landscape, followed by a story about a family of children who form their own resistance group against the Nazi occupation of the Channel Islands, which, I think, says a lot about Scott’s interest in heroes who are outsiders.

Your partnership with Scott is remarkable in hindsight given that you’ve said you never met while working on Marney nor even spoke on the phone. What were the practicalities of that collaboration and was that the usual working practice at IPC at the time?

I would receive a script in the post on, say, a Tuesday and the finished work would need to be posted by the following Tuesday at the latest. As far as I remember there was no discussion at the start of the series, no conversation about artistic aims, just a request to take on this new story. There was no question of submitting roughs, character studies or anything of that sort, the artist just got on with it. It wasn’t until I began to work for Dez Skinn on The Black Knight that I was asked to submit character and costume sketches. The artist was totally trusted and I don’t recall a single instance of a page being sent back for correction. This was the case with all the many strips that I produced for Fleetway/IPC.

Can you tell us a little about your artistic process on Marney? Was there room for experimentation with the strip?

When I received the script for episode one of Marney I realised at once that this was something special, and that I would never have another opportunity to explore the Natural World with this degree of realism. It was so unlike any other strip in British comics of the day that I regarded it as a unique chance to explore and revisit the style of pen and ink illustrators that I had discovered at Art School, people like Arthur Rackham, Edmund J Sullivan and even going as far back as the woodcuts of Thomas Bewick.

I remember hearing an interview with Bob Dylan in which he recollected the writing of ‘A hard rain’s a’gonna fall’. He said that it was written at a time when nuclear disaster felt imminent, when two belligerent powers were on the brink of a nuclear exchange (hey, guys, thank goodness we will never return to those days, eh?) and that every line was an idea or a genesis for a future song, but he felt he had to use them now or he might never get the opportunity to use them again.

I remember hearing an interview with Bob Dylan in which he recollected the writing of ‘A hard rain’s a’gonna fall’. He said that it was written at a time when nuclear disaster felt imminent, when two belligerent powers were on the brink of a nuclear exchange (hey, guys, thank goodness we will never return to those days, eh?) and that every line was an idea or a genesis for a future song, but he felt he had to use them now or he might never get the opportunity to use them again.

I felt the same about Marney. Every panel was an unrepeatable opportunity for a landscape or a wildlife study, and I probably overburdened the story with details of nature and animals, because I felt that I wouldn’t get the chance again. And I was right. Until Keith Richardson (of Rebellion) contacted me last year to provide a cover I haven’t produced that style of work again.

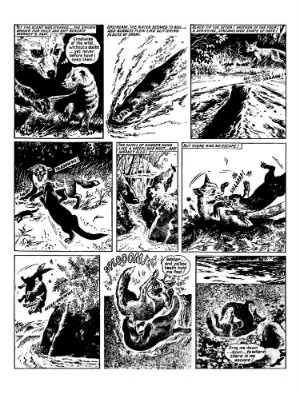

I realised at once that if I was to reproduce the infinite variety of the natural world I would need more texture than a pen and ink could provide, so I experimented with inky fingerprints, spatter from an old toothbrush and a more regular spray from a diffuser tube. The amount of pages I was producing a week didn’t allow time to experiment on roughs, so I just laid into the finished pages with whatever came to hand, and worked into it until I was satisfied with the result. I don’t recall things going so badly wrong that I was forced to abandon a page and start again. I guess I was just lucky ( or easily satisfied).

Seeing Marney collected again now in one place are there any particular stories that stand out as favourites?

I think every episode presented its rewards and its challenges, but the sequence of the flood stands out as a favourite, together with the winter scenes, the hunt and the rearing of the orphaned cubs.

What’s incredible looking at those stunning illustrations of not just wildlife but also environment and countryside in Marney is that this is a comic created decades before the easily available photo-libraries of today. So in terms of reference material what were your resources?

Photographic reference was really hard to come by, as at that time the fox wasn’t particularly well regarded. I found a paperback about a coven of foxes with about half a dozen reasonable pictures, a few I Spy and Ladybird books and a few pictures cut from magazines. National Geographic and Readers Digest had a poor reputation among artists at the time as a result of some highly publicised copyright cases, so I tried to steer clear of them. It was really difficult so a lot of the time I copied expressions and body movements from my two rough collies and adapted them.

Without actually being graphic Marney is a very uncompromising comic in a lot of ways – death and nature at its most unforgiving is a recurring motif. Were there any concerns either editorially or from outside feedback at any time about story content?

It was never mentioned. As I have said elsewhere, the story divided opinion, but I tended to think that people disliked it for its sentimentality rather than its brutal realism. It wasn’t until I saw the pages collected into a book that I fully realised how much existential angst poor Marney has to suffer! As some reviews have pointed out, it can be quite a hard read!

What were the logistics of producing the strip in terms of output? How far in advance were you working on it? And how many pages would you typically be working on in any one week?

Looking back I am a little incredulous at the amount of work I was producing every week. For example, in the spring/early Summer of 1974 I was drawing two weekly pages of Fishboy, two pages of Marney and just finishing the run of The Last of the Harkers. In addition I fitted in short runs on Kelly’s Eye, Nipper and a story I barely remember called The Prisoner of Zenga, covering for South American artists, in the period between 1973 and 1976. So, six or eight pages a week on average. The pages would be finished a week after receiving the script and published within four or five weeks of completion. I’m not sure how I kept it up, and even less sure how I avoided a divorce!

In terms of the strip’s contemporary popularity how was it received because it’s very atypical in some ways to the other adventure strips that would have appeared in Buster which was still essentially perceived as a “boys paper” at the time…

As I remark in the introduction of Marney the Fox, it was a strip that sharply divided opinions, and it regularly topped the most and the least popular lists that Editor Len Wenn kept. I loved it, and gave it my best, but I can’t help noticing that in interviews with Scott, and in his obituaries, he seldom mentions it as being among his favourites.

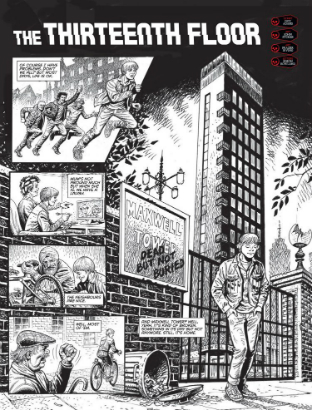

John worked with Steve Parkhouse and Paul Neary on the Black Knight strip in Hulk Comic for Marvel UK (left). On the right is a page from his return to The Thirteenth Floor in the recent Scream! and Misty Special from Rebellion

Did you ever imagine the day would come when Marney the Fox would be reprinted in such a gorgeous deluxe edition?

Never in a million years! It has come as such a wonderful surprise and the book’s reception has been tremendously gratifying.

The nostalgists are a fine audience for Marney of course but would the book finding a new audience of children be the cherry on the top for you?

That would be great. Is there any way that sales figures can be used to provide that sort of information?

Moving on to some of your recent work for Rebellion, you were one of the artists on the The Thirteenth Floor revival in their recent Scream! and Misty Special. How did it feel returning to the fictional worlds of IPC again in 2017?

I was always an admirer of the strip, although I had forgotten that I had provided the artwork for a summer special, so I had already had a shot at duplicating Jose Ortiz’s style (below). It felt great to slip back into the IPC fold after such a gap!

In your hugely impressive career you’ve worked on everything from Doctor Who to Star Wars, the peripheries of the super-hero world on L.E.G.I.O.N. at DC and cult classic The Black Knight for Marvel UK, and boundary-pushing comics like The Invisibles. Of all your vast body of very different cross-genre work are there any comics that stand out as particular favourites?

As I have said, Marney always felt like something very special, as was the moment when an Alan Moore script dropped onto the doormat. What three impossible things would I be called on to draw this time? The Black Knight was a high point, too. It was my first foray into the world of fantastic heroes and creatures, and I enjoyed every minute of it. Steve Parkhouse’s scripts were a terrific mix of folklore and wild invention, and I learnt so much from working with Paul Neary.

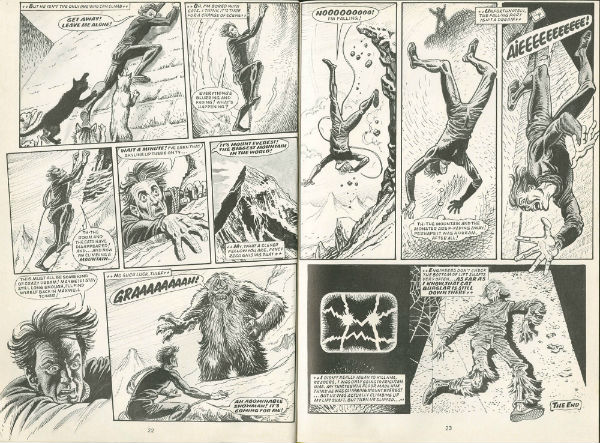

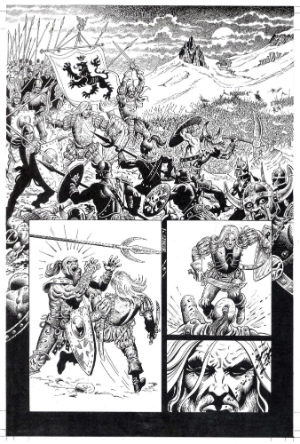

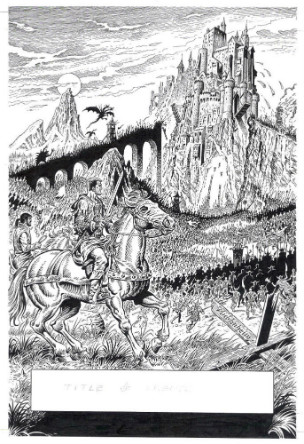

Samples of John’s Warhammer work including ‘Hildebrand Grimm’ right

Another series of stories that made me feel that I had to up my game were the strips I produced for Warhammer monthly, from excellent scripts from James Peaty and Mitchell Scanlon. The magazine closed down much too soon, and one story, ‘Hildebrand Grimm’ sadly never saw the light of day. If that were revived I would feel my career had come to a fitting end.

You can follow John Stokes on Twitter here and order Marney the Fox from the Treasury of British Comics site online here priced £9.99 for digital or £17.99 for print. Read our Marney the Fox review at Broken Frontier here.