Obviously there’s a lot of gross stuff flying about in (most) David Cronenberg films, but when I first encountered his work as a gore-hungry teen, I’d already had access to the internet for a fair few years. I’d seen stuff. The more destabilising aspects were the fact that the stories didn’t unfold in the way I understood narratives to work. The rules of plot, of cause-and-effect, of tidy resolution or else poetic ambiguity; of easy-to-follow character identities and arcs; that kind of thing. Why was James Woods saying that? You mean there’s more after the heads explode? Why wouldn’t you simply leave the apartment building full of psychotic nymphomaniacs? These were stories animated not just by the storyteller’s thrill at creating a world, but by the irrational libidinal energies and urges I was only just starting to become aware of myself.

I mention my age in that context because I think that’s as much a key to getting a handle on John’s Worth as situating the book in the psychedelic body horror tradition of Cronenberg. I’m too old and haggard and humble to go around naming microgenres, but I still can’t help identifying them, that taxonomising instinct one of the most persistent within the enthusiast’s set of peccadillos. That means that, when faced with Jon Chandler’s fantastic, grubby, bizarre work, it’s difficult to resist drawing comparisons between it and other, similar artists with which it shares an orbit: Michel Fiffe’s COPRA, the work of Benjamin Marra, Tom Scioli’s IP-based output. Each holds the charge of unfettered creativity we associate with children playing, as well as the lesser-acknowledged fetid urge for kids to smash their toys together. Those self-same libidinal impulses are equally indulged as Action Men, their more easily flammable clothes removed, have their plastic flesh melted in microwaves. Chandler’s work shares this fecund vibe, this feverish energy — thin, sketchy ink lines, as if drawn in exercise books held half-open so the teacher can’t see what you’re up to — and cartoonish ultraviolence.

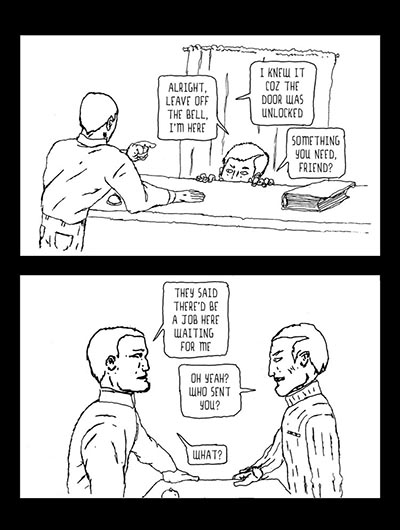

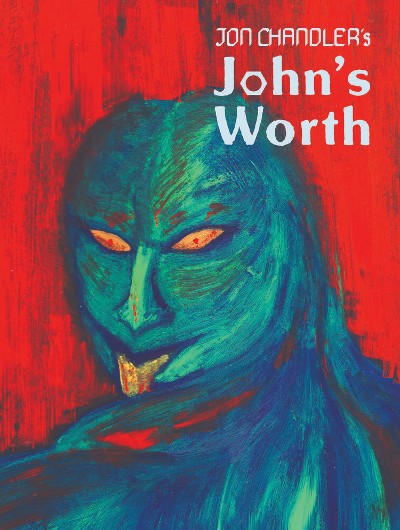

John’s Worth synthesises innumerable influences (not just Cronenbergian body horror but the staging and excess of eighties action films, Philip K Dick paperbacks with their lurid covers and tales of shifting identities, internet conspiracy theories) into a six-issue miniseries, originally published and collected here by Breakdown Press. Its cover and credit pages give some clue of what will come later: a cosmic-horrific collapse of identity and fleshy humanity, by dint of a William Blake-via-Mat Brinkman series of horrific portraits. After that bit of demonic foreshadowing, things return to being a trifle more earthbound. The story opens on the eponymous army veteran John, fresh from a tour in God-knows-where doing God-knows-what, as he begins taking on less reputable work at the behest of an unseen criminal employer. His aptitude for killing apparently makes him quite the asset, as one imagines it would in such careers.

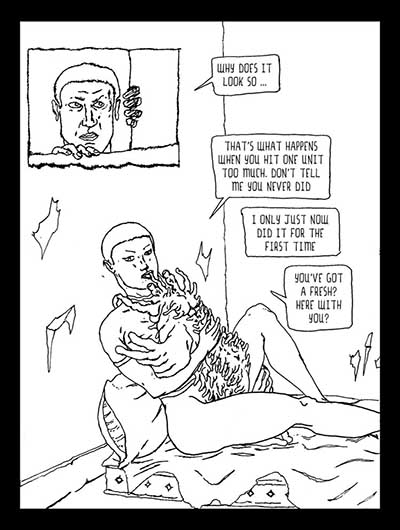

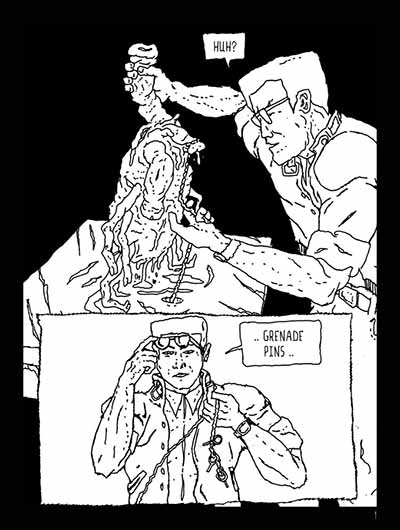

He’s swiftly initiated into this world’s principal vice — Special Personal Eyes eXperience (yes, I love it also) units, or SPEX, a eXistenZ-esque fleshy gadget that’s as “addictive as crack” and allows the user to enter another realm of reality. Sort of. Maybe. You know the score with these stories: what shaky grasp you had on what was “really” happening within this fictional construct almost immediately wriggles free from you completely, around about the same time you learn that SPEX are evolving squid-like creatures its users interact with using seemingly every available orifice. Woods only ever kissed that weird living TV with Debbie Harry’s lips. Chandler pushes things much further, in a scary-erotic psychosexual tableaux the creator of Videodrome would (and should) be jealous of and troublingly aroused by. It certainly prodded at some buttons that I — a man now at the end of his life, remember — recognise as being those self-same intrigued/scared reactions to Cronenberg et al I had in adolescence.

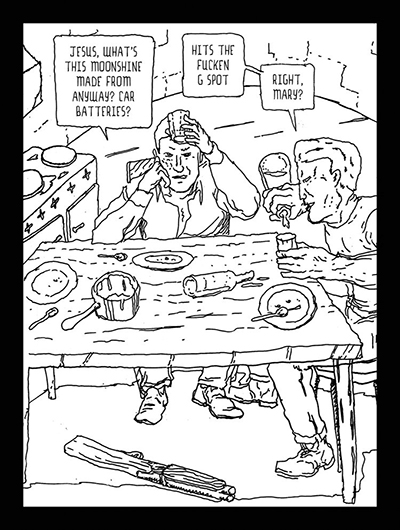

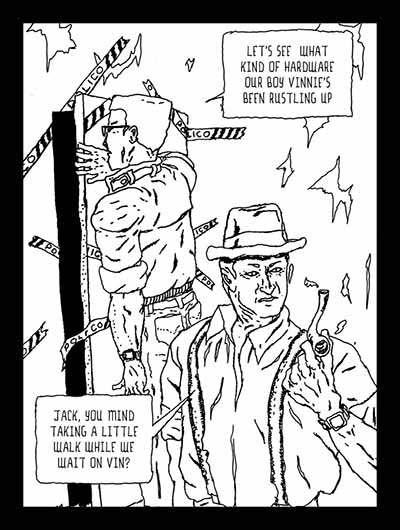

As the scope of John’s Worth expands beyond familiar conceits and consciousness, so too do the pages open up. The first issue is told in a series of two-panel pages, bordered by a black expanse. The second portrays consecutive action sequences in full-page panels, or else as discrete movements rendered in white ink-on-black. The knowingly-cliche hard boiled dialogue and gleefully goofy made-up jargon fills the expanses the characters occupy when they’re not running, diving, or firing assault weapons. The action moves through a number of familiar settings and characters: a post-apocalyptic fight for survival in the desert; a spell spent holed up in a remote base, waiting for a surely-incoming attack, like a Howard Hawks western; an all-out assault on the presumed bad guys that sees former enemies putting aside their differences. Chandler’s art shares a grungy physicality with the aforementioned comic forebearers/inspirations, which puts it and them at odds to the plasticy roundness of mainstream comics, despite their gestures towards the work of Image founders like Liefeld and Lee; the latter appears more in the vein of Shaky Kane, of faux-naive splash pages, details and poses, a performative coolness belying the nasty shit writhing beneath the surface.

But again: is any of that really happening? The barriers of reality start coming apart long before the panel borders themselves start to crumble into darkness. John struggles to hold onto his sense of self, introducing himself as “Johmk” to a couple of new acquaintances. He finds himself cut adrift in the criminal world, unsure of his place or of how things work, yet is eminently nonplussed when confronted with a penis-headed monster which is either his SPEX unit evolved into a bipedal being, or a physical embodiment of his ID, or both. Struggling to centre himself in any kind of reality, John greets another character one morning with “Did you sleep well…Is that the kind of thing people say?” like somebody mired in a bad trip trying to come down, or a child parroting phrases they’ve heard adults say.

“Why do anything, of any effort, if it gets forgotten so easily?” is a question asked late in the game of John’s Worth, a nod to the ephemerality not only of play, but of pulp entertainment, and comics especially. It’s perhaps not a spoiler to reveal that things start to shift towards cosmic horror in the final stretch of this, as promised by those opening images. It’s interesting to note how many of the genres Chandler invokes (and perverts) the tropes of share the same third act twist. Whether it’s Lovecraftian horror, hardboiled noir or direct-to-video thriller, our protagonist often discovers they’ve been “played.” Their actions were not of their own free will, but encouraged in part by some larger shadowy power, and oftentime this revelation doesn’t blow the whole thing wide open so much as simply identify their own small part in a much larger scheme they cannot comprehend. That perhaps suggests a tidier structure to John’s Worth than I set up in the opening paragraph, and that would only be half-correct: there’s a shagginess to the story even when it appears all the pieces are lining up, the feeling that the real “answers” are just beyond your grasp.

Chandler plays a long game with remarkable confidence here, consistently pulling the rug from beneath reader and character alike and retaining a perfect poker face after each such twist. Legitimate horror hovers on the edge of every panel, even the ones that appear more like an Action Force fan comic or punk zine. A properly nasty, brilliantly conceived body horror spectacle that hangs together while leaving enough wriggle room for the weird stuff — and there’s a whole lot of that in there, like the worms writhing under the skin of a bad trip.

Jon Chandler (W/A) • Breakdown Press, £19.99

Review by Tom Baker