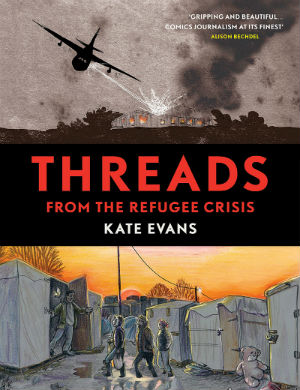

BROKEN FRONTIER AWARDS – BEST GRAPHIC NON-FICTION WINNER!

We talk a lot about the many unique ways in which comics – and particularly autobiographical comics – forge an intimate connection between creator and audience here at Broken Frontier, and their power to pull the reader so fully into the experiences of the artist. In the pages of 2017 Broken Frontier Award-winning Threads: From the Refugee Crisis, Kate Evans documents life in the Calais Jungle – the much publicised refugee settlement in France – from the perspective of a volunteer helper, fully exploiting the empathetic qualities of that artist/reader bond to present an uncompromising piece of graphic journalism.

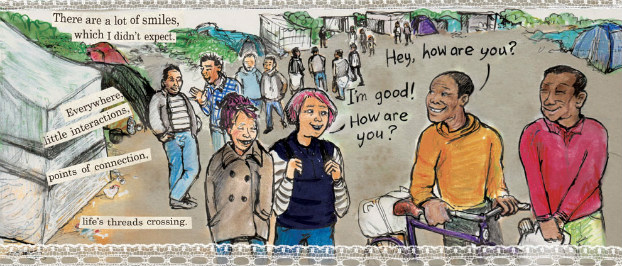

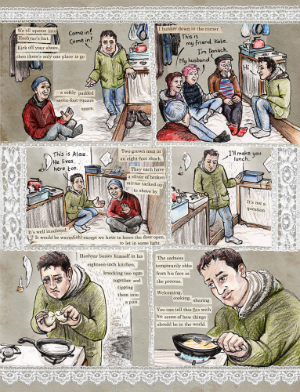

Providing a potent counterpoint to the scare-mongering excesses of tabloid newspapers, Evans recounts her time in the Jungle, the poignant stories of those she met and the practicalities of the day-to-day trials of living there. We observe, for example, her feelings of ineffectiveness as she’s put in charge of the three padlocks available for the thousands seeking the illusion of security for their makeshift homes. We watch as she assists in the unloading and distribution of provisions. And we witness her interactions with the camp’s residents – playing invisible cricket, listening to their testimonies and drawing their portraits.

Providing a potent counterpoint to the scare-mongering excesses of tabloid newspapers, Evans recounts her time in the Jungle, the poignant stories of those she met and the practicalities of the day-to-day trials of living there. We observe, for example, her feelings of ineffectiveness as she’s put in charge of the three padlocks available for the thousands seeking the illusion of security for their makeshift homes. We watch as she assists in the unloading and distribution of provisions. And we witness her interactions with the camp’s residents – playing invisible cricket, listening to their testimonies and drawing their portraits.

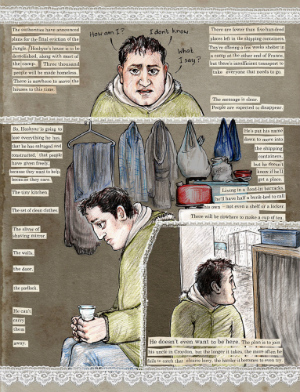

Throughout, Evan juxtaposes the viewpoints of those with no direct understanding or appreciation of the circumstances with her direct experiences. We’re reminded of the inhumanity of politicians whipping up fear around the situation for political gain, of the violence perpetrated on the refugees by the locals and, interspersed throughout via the symbolism of an iPhone screen, the prejudiced and ignorant viewpoints of those too ready to adopt a Daily Mail mentality. This latter motif is a quietly devastating technique that simply allows the bigotry to speak for itself with no need for further commentary.

There are uplifting moments as well, though. A simple but quite beautiful sequence where a colleague speaks of how the shared experience of making art with felt tip pens united a group of grown men is particularly affecting, and the welcoming nature and generosity of the refugees always stands out. But every page is still steeped in the stark squalor of their living conditions and the inescapable tragedy of their situations.

So often what Evans portrays here threatens to overwhelm the reader. The inexcusable truth that the relief effort means the authorities step back from their own responsibilities to the refugees; police checkpoints targeting and stopping dry bedding getting to those in the camp; the lack of facilities to even sterilise bottles for babies; the moment where she meets a formerly vibrant child now drained of hope from their ordeal; and the dehumanising brutality that those who have already endured so much are forced to face simply for the perceived crime of wanting a better life for their families.

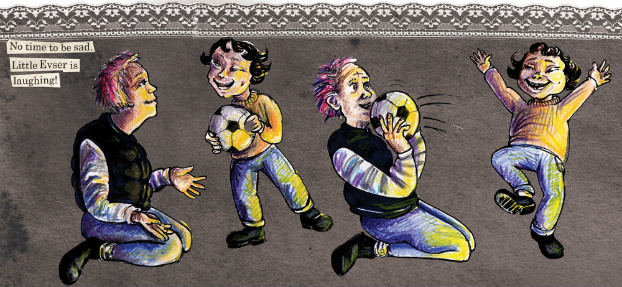

It’s difficult to step back from the emotional impact of Threads to discuss Evans’s craft but it’s vital to do so to look at the ways in which she uses the form to emphasise its themes. Calais is renowned, of course, for its historical lace-making industry and that’s reflected in the ornate panel borders of the comic that act as a powerful contrast throughout with the raw drama within them; a visual metaphor for the individual threads of the refugees’ lives being pulled together here. Evans’s panel usage is deliberately erratic, idiosyncratic and individualistic in structure and utterly brims with movement and life as a result, while her art has a raw realism to it. Visual characterisation is notably acute and expressive.

While Threads is a remarkable example of graphic journalism it feels far more than just reportage. It asks us not just to examine the social reasons behind a humanitarian crisis but also to question our own complicity in its inherent injustices. This is not an easy book to read because it will upset you and it will anger you. And so it should. Threads seeks to shake us out of our complacency and underline that our sense of social justice comes with responsibilities. It’s also a reminder that the constructed “truths” of sections of the right-wing media cannot and must not be left unchallenged.

This vitally important example of graphic journalism is full of stories that, in isolation, may seem smaller and transitory but nevertheless they have universal importance. Episodic and fragmentary in nature, its narrative perfectly reflects the uprooted lives of those it depicts. What Evans has achieved here transcends the topicality of its subject matter. It’s a plea to embrace our own humanity and a calm but searing indictment on those who demonise, fabricate and excuse rather than recognise the terrifying realities of a global crisis.

Kate Evans (W/A) • Verso Books, £16.99