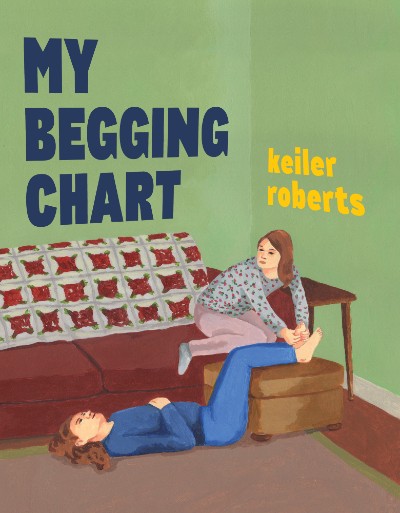

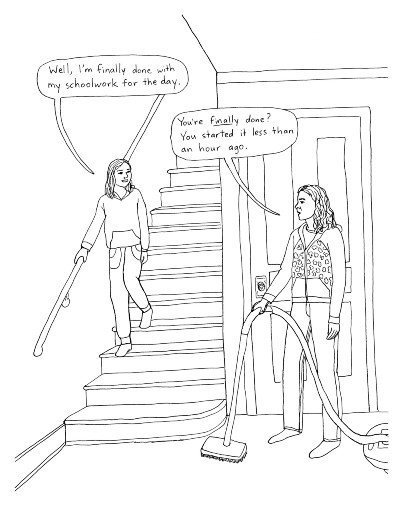

Trying to describe My Begging Chart, the new book by Keiler Roberts, is like trying to capture what everyday life is like: we all seem to think we can explain it, but inadvertently struggle because there are a million things to potentially focus on. Roberts has an uncanny knack of highlighting the right kind of moments, pulled seemingly at random, that draw aspects of her life as a woman, mother, daughter, or spouse, into sharp relief.

Looming silently as a backdrop to these quotidian events is a chronic illness, colouring how Roberts engages with people around her. She lets it all hang out, literally and metaphorically, allowing readers into her home, and giving us an inkling of what it means to be in her shoes.

Looming silently as a backdrop to these quotidian events is a chronic illness, colouring how Roberts engages with people around her. She lets it all hang out, literally and metaphorically, allowing readers into her home, and giving us an inkling of what it means to be in her shoes.

There is subtle humour in these spare panels, offset by the deadpan manner that Roberts uses to dissect her life for our benefit. The result is a powerful memoir that is instantly relatable as well as strangely moving. We asked Roberts about her influences, why she continually engages with body image, and how coping with a pandemic has affected her work. Here’s what she had to say.

BROKEN FRONTIER: A lot of your work has focused on social anxiety and I was wondering if the pandemic had an impact on how you look at your chosen medium of expression in any way?

KEILER ROBERTS: I don’t have social anxiety as often anymore. Maybe writing about it actually helped! Or else it’s just that I have more anxiety about other things, and there’s only so many things I can be obsessively anxious about. The pandemic and climate change have certainly impacted how I think about art and life – not just comics. Everything feels more fragile and less permanent. There are so many more ways for art objects to be damaged or destroyed with heavy storms and flooding or fires. When I switched from painting to comics, a huge part of that was wanting to make something that could be widely distributed, where there was no precious original object that someone would have to care for and protect. Or maybe it has nothing to do with any of this, and I’m just coming to terms with how much I despise framing and hanging artwork. There’s no part of comics that I hate to the degree that I hate that. I just can’t handle the pressure of having to be very careful.

BF: You have spoken, in the past, of how comics were your replacement for painting. Does the latter still impinge upon how you approach the former?

ROBERTS: I don’t think painting ever impinged on my approach to comics, so I may not be understanding your question. Part of what drew me to painting was my love of two-dimensional images. I love photographs too. Sometimes I take a picture of where I am, and then look at the picture instead of looking into real space, because I get more pleasure out of it. I love composition, and this is part of comics and painting equally.

BF: Early readers of My Begging Chart say it reminds them of books like James Kochalka’s American Elf or Jeffrey Brown’s Clumsy. Were there writers working in other genres who informed the way you write about families?

ROBERTS: Lauren Weinstein, Glynnis Fawkes, Carol Tyler, and Summer Pierre were the cartoonists who inspired me with their depictions of families in comics. I watch a lot of TV and movies. I’m really excited by characters who don’t completely fit in, act in surprising ways, and are true to themselves. It’s even better if things work out for them. Enlightened is one of my favorite shows. It didn’t last long, but the writing and acting were amazing. I haven’t seen any equivalent of that show about families or children.

BF: Body image continues to be an important aspect of your work. Do you think conversations about it have evolved since when you first began incorporating the topic into your comics?

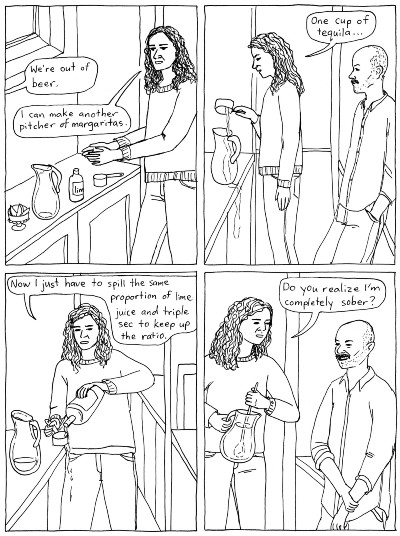

ROBERTS: My naked body shows up in every book, but I’ve never explicitly written about how I feel about my body – which is what “body image” usually refers to. The conversations about body image have definitely changed, but the idea of body positivity is still a judgment and still links self-worth to how you feel your body looks. What I’ve been trying to do is insert nudity without it being about sexuality or self-esteem. What are the other conversations you can have about bodies? A situation or conversation is usually funnier when someone is naked, especially when it’s a mom yelling at her kid.

Bodies are also discussed in terms of ability or lack thereof. According to body positivity, if you don’t think you’re attractive enough, you can be grateful for all the wonderful functions your body does. This can lead to other problematic thoughts because our bodies often betray us in function just as much as they do in appearance. I don’t want to show my body in a sexual, judgmental, or celebratory context. I’ve also drawn myself naked at the spa with friends. In this case it’s not just for humour, but reflects solidarity. When you can be casually naked with your friends it shows a deep level of comfort.

BF: You were recently invited to an event featuring writers and their stories about mothering. Does that feel reductive, as an artist?

ROBERTS: No, but this question feels a bit reductive to me as a mother, ha ha! I’m just kidding, but mothers deserve more respect. Being a mom has challenged me and rewarded me in the greatest ways. It’s a crime that parenting and care-giving of any sort isn’t one of the most respected actions in our culture. Also, maybe it’s a bit of a problem that the mothers that get the most attention are people who are successful in other fields. Nobody is paying attention to the moms who never got around to writing a memoir, but they have so much wisdom!

BF: You once said that you enjoyed writing more than drawing. Why do you think that is?

ROBERTS: I’m sure I said that at some point, but I think it has changed. During My Begging Chart, I really leaned into drawing and let the visuals do more of the storytelling.

BF: Coping with chronic illness is hard at the best of times, let alone during a pandemic that has wreaked havoc in all kinds of ways. How optimistic are you, as an artist and mother, about the world and where we are headed?

ROBERTS: It depends on my mood. My puppy was just sick for a week, which made me very pessimistic about my whole life and future. He’s doing a bit better today, so I feel like everything is going to be good forever. My sense of the future is not to be trusted or taken too seriously! At any point I could look at evidence for positivity or negativity in art, parenting, chronic illness, and the world, and could always find plenty of evidence to support either outlook.

One of the days I cried hardest this year was after my daughter’s horse died in Minecraft. It was a bigger emotional event than the day our real dog, Crooky, died. Stress, anxiety, grief, optimism, thought, and emotion are all illogical and mysterious forces in my life.

BF: It has been a difficult year, and I was wondering if you had any recommendations in terms of books that have helped you get through the past few months.

ROBERTS: I had read The Little House on the Prairie series (Laura Ingalls Wilder) to my daughter before the pandemic, and I thought about them a lot throughout – especially The Long Winter. They helped remind me that the situation was temporary. It took me several months before I could focus and enjoy a novel and stop reading Covid news constantly. I think most novels would be helpful in getting me through hard times, but the one I read during the most intense lockdown period was The Memento by Christy Ann Conlin. I’m fascinated by the way a novel, song, or other artwork becomes folded into all of my memories of the time when I read it. I’ll never separate that beautiful book from the extreme sense of anxiety and uncertainty of the early pandemic. It’s the phenomenon of bonding with someone when you go through something hard with them. I bonded with that book. I recently got to put together a whole bookshelf of recommendations for Librairie Drawn & Quarterly. Here’s a link!

Interview by Lindsay Pereira

[…] Pereira speaks with Keiler Roberts about My Begging Chart, the impermanence of art, the joys of composition, and the humor of […]