As if it’s taken this long for a Gillen and McKelvie joint to take the form of a bona fide murder-mystery story? It’s like when J.K. Rowling did her straight detective novels, and the realisation hit: this is what she’s been doing all along. There’s just no wizards this time. So far each of the comic collaborations between artist Jamie McKelvie and writer Kieron Gillen have had the structure of a mystery, and The Wicked + The Divine especially has parcelled out information in thin slivers, with just enough to keep the audience engaged and guessing. But this, the third stand-alone special in the series, is the first proper whodunit. It’s even explicitly modelled on an Agatha Christie book!

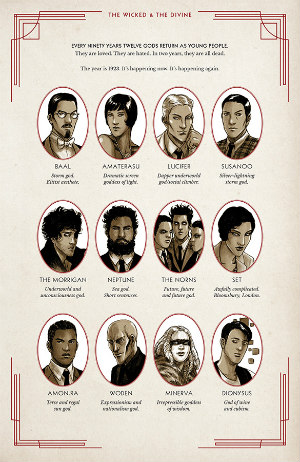

Of course, it doesn’t follow the plot of And Then There Were None — where a group of strangers with dark pasts are mysteriously assembled on an island and bumped off, one by one — to a tee. The conceit of WicDiv (as all the cool kids are calling it) is that, every ninety years, a classical pantheon of gods is reborn in modern form. For the main series, the gods return as pop stars. Some are immediately comparable to certain real-life chart-toppers, but it’s clear that it’s not a one-for-one comparison. Here they take the shape of turn-of-the-century modernists and, much as the Christie story serves as a starting point for the plot, it’s not as simple as “this god is this writer, this god is this artist,” etc.

Of course, it doesn’t follow the plot of And Then There Were None — where a group of strangers with dark pasts are mysteriously assembled on an island and bumped off, one by one — to a tee. The conceit of WicDiv (as all the cool kids are calling it) is that, every ninety years, a classical pantheon of gods is reborn in modern form. For the main series, the gods return as pop stars. Some are immediately comparable to certain real-life chart-toppers, but it’s clear that it’s not a one-for-one comparison. Here they take the shape of turn-of-the-century modernists and, much as the Christie story serves as a starting point for the plot, it’s not as simple as “this god is this writer, this god is this artist,” etc.

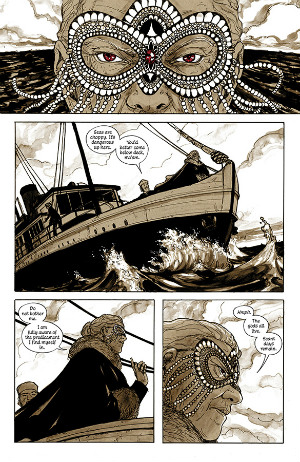

The sea god Neptune, who is said to hate adjectives and is a hyper-masculine beardy-type is clearly a Hemingway type; but as a hulking figure doomed to die at age 21, his biography does not leave room for an Old Man and the Sea, and his skin tone suggests something of the Captain Nemo mixed in there. Similarly, The Morrigan is an eye-patched Irish gadabout who narrates his life out-loud in an experimental formalist fashion, but he isn’t just James Joyce-turned deity; nor is the dandy Lucifer solely F. Scott Fitzgerald with an even more pronounced death drive, or the “awfully complicated” set entirely Virginia Woolf, and so on.

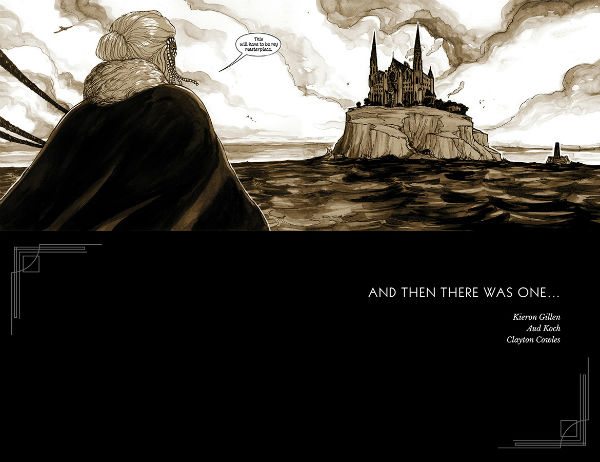

A propensity of literary types in the cast has called for a switching of gears in terms of how this particular one-shot is delivered to readers. Each of these specials so far has allowed McKelvie a much needed break, whilst delivering another issue during the customary Image Comics hiatus-between-collections, with a guest artist joining Gillen. In this case it’s the Portland-based Aud Koch, whose sepia-toned, ink-wash style evokes both the period setting and the pulp paperback origins of the plot. Unusually, though, her contributions are broken up by long prose passages which tell the bulk of the story. The traditional comic portions come during dramatic moments. Which is to say, when people are found with their heads exploded.

Gillen himself has noted that there is a precedent for such formalist experimentation, including the later prolex-laden issues of Dave Sims’s Cerebus and the throwback pulp issue of John Cassaday and Warren Ellis’s Planetary. The Wicked + The Divine: 1923 might actually be closer to the wonderful work of Posy Simmonds, which often stands on the precipice between these comics and prose, and takes literary classics as a starting point. Except this immediately gets a lot more bloody.

Gillen himself has noted that there is a precedent for such formalist experimentation, including the later prolex-laden issues of Dave Sims’s Cerebus and the throwback pulp issue of John Cassaday and Warren Ellis’s Planetary. The Wicked + The Divine: 1923 might actually be closer to the wonderful work of Posy Simmonds, which often stands on the precipice between these comics and prose, and takes literary classics as a starting point. Except this immediately gets a lot more bloody.

The story here involves the gods, in the late stages of their two year life cycles, being gathered on a remote island off the coast of America, where Lucifer has constructed a blasphemous chapel (there is as much Jay Gatsby in the character as his creator). It’s here that Ananke, the ancient figure who has perpetuated through each “recurrence” and mentored the resurrected gods, has plans to off the lot of them. The characters don’t know it, but readers of the series are aware that behind the grandmotherly airs Ananke has a significant bloodlust.

Which is a page-turner in and of itself, especially because of how it deepens readers’ understanding of the main, modern-day storyline (in fact the very first issue of the series opens with the remaining 1923 gods gathering around a table). This being WicDiv, there is a larger allegory to all the death and destruction. T.S. Eliot is among those adapted to god-form, as the “elitist aesthete” storm god Baal. The IRL Eliot one described the IRL James Joyce’s style as the “mythic method,” which the poet explained meant he used the classical past to give “a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility that is contemporary history”. It’s also a decent description of what Gillen and McKelvie (and colourist Matt Wilson, letterer Clayton Cowles, and Aud Koch this time around) have been doing throughout The Wicked + The Divine.

Besides being pop stars, adored by many and hated by some, the modern-day deities have been tasked with battling back “The Great Darkness.” It sounds symbolic, but it has appeared as a very tangible threat several times in the book, and a black cloud taking terrifyingly huge humanoid form to attack the gods where they live. This being comic books, a thing can be both symbolic and literal at once. Here, the forces of darkness that the cultural icons are doing battle with are more obvious.

Besides being pop stars, adored by many and hated by some, the modern-day deities have been tasked with battling back “The Great Darkness.” It sounds symbolic, but it has appeared as a very tangible threat several times in the book, and a black cloud taking terrifyingly huge humanoid form to attack the gods where they live. This being comic books, a thing can be both symbolic and literal at once. Here, the forces of darkness that the cultural icons are doing battle with are more obvious.

Early in one of the prose sections, the Norns (a triplicate god modelled here variously on Orwell, Huxley and Wells, each offering their own predictions for the future) have a vision of a forthcoming war. Dionysus, a god whose physical form sometimes distorts into abstract blocks, patterned after Picasso during his cubist period, echoes this in his own premonition: “Cities burned from fortresses in the sky. Ovens…full of people. It’s there. It’s coming. There’s nothing we can do.” Both statements get a sharp rebuke from military veteran Neptune. It’s redolent of J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls, a play which, like the 1923 special, was set between the two World Wars but had the benefit of being written after them.

In Priestley’s play the dramatic irony of the upper-class twits being satirised is fairly trite, their assertions that there deffo won’t be another war and that big ole Titanic is unsinkable serving to illustrate their disconnection from reality. What’s different here is that we see, for the first time, a pantheon who seem perfectly willing to embrace the “Great Darkness,” in this case embodied by the encroaching First World War.

A couple of the gods appear sympathetic to the nascent National Socialist party over in Germany, mirroring the real-life (and often undiscussed) dabbling with anti-semitism and Fascism that the Bloomsbury set especially engaged in during the Twenties, and which artistic and intellectual classes have been flirting or downright embracing with since time immemorial.

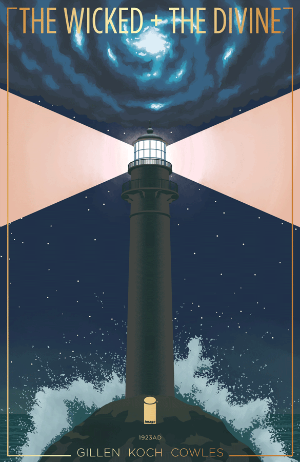

Not that there aren’t “cute” gags amongst all the highbrow subject matter, like one of Gillen’s prose sections describing the sky as an ink wash, precisely after a double-page spread where Koch has used that very technique; or the chapter headings that explicitly riff on the inspirations for each god, “Dionysus’ blown-apart period” indulging the writer’s propensity for puns he otherwise manages to keep contained in the contaminated zone of Twitter; and, since this is still a genre piece, a comic book inspired by a murder-mystery novel, the story is peppered with great concepts, like the stuttering projected butlers that tend the island, the climactic finale in a lighthouse, and text boxes in the comic sections modelled after captions in silent movies.

As with the previous formalistically experimental issues of the book, there is a reason for the change in style, besides it being a fun artistic challenge. McKelvie’s bright, bold, fashion-forward visuals are perfect for the present-day Pantheon of image-conscious pop performers. When we’re stepping back to a pre-Popjustice era, with a cabal of gods patterned after writers, it makes sense their story would be told (largely) through prose. And even with the expanded 52-page issue, Gillen and Koch have precious little time to introduce us to all these characters, their relationships, their wants, needs, and grudges, where the mainline WicDiv story has taken a few years to explore those elements.

Anyway, that’s all well and good, but what does it all mean? The interplay of high and lowbrow, the refusal to let the artistic classes off the hook when it comes to their seduction by the right-wing, gods and monsters and murder and mayhem? The Wicked + The Divine is similar to past Gillen and McKelvie work in that it’s an explicit meta-commentary on the context it’s being produced in.

Anyway, that’s all well and good, but what does it all mean? The interplay of high and lowbrow, the refusal to let the artistic classes off the hook when it comes to their seduction by the right-wing, gods and monsters and murder and mayhem? The Wicked + The Divine is similar to past Gillen and McKelvie work in that it’s an explicit meta-commentary on the context it’s being produced in.

Phonogram was a nostalgic comic about Britpop, an entry in the poptimist/rockism wars which were going on if you were a sensitive indie boy with a Los Campesinos! t-shirt and a Drowned in Sound forum account, and a deeper examination of how pop helps form identity. Young Avengers had its characters facing evil copies of their parents as part of a larger discourse on legacy characters, the book’s own existence as the second volume of an older series, and how continuity is a tricky thing in the revolving-door creative teams of superhero comics. Also, bisexuality.

The Wicked + The Divine is about fandom, and has subsequently inspired its own rabid and creative community of readers, but it’s also about the “purpose” of art and culture, and about the amount of influence those in the privileged position to work in those fields wield, and how they are often attracted to fascism (in the basic terms, this can often be boiled down to “left-wing politics is all rules and being told off, right-wing politics says I can do whatever I want, woo artistic freedom at the expense of all else!”) It’s a strong topic at a particularly timely juncture, although one which requires a level of familiarity with 20th century art, literature and history. In this case, at least, the dense layers of allusion, parody and criticism are actually saying something.

Kieron Gillen (W), Aud Koch (A), Clayton Cowles (L), Jamie McKelvie, Matt Wilson (CA) • Image Comics, $4.99

Review by Tom Baker