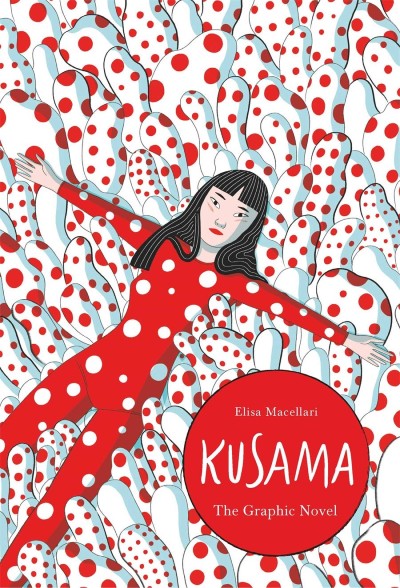

Yayoi Kusama is a fascinating artist. Caught in the finite net of Elisa Macellari’s deft graphic biography, she becomes our fascinating friend for a moment.

Kusama, first published in Italian by Centauria, is out now in translation by Edward Fortes from Laurence King Publishing.

The Japanese artist embodies the contradiction of being the centre of a cult of personality, whilst making work that centres obliteration of any sense of self. If your knowledge of Yayoi Kusama stops at dots and pumpkins, and you’d like to know more about the sex happenings and hallucinations, look no further than this concise and engaging graphic novel. Following, more or less, the thread of Kusama’s own 2013 autobiography Infinity Net, Macellari shows and tells us Yayoi’s story from childhood and frustrated artist status in Japan, through to being an impoverished and then powerful artist in New York in the 1960s, to the iconic cultural status she achieved in later life, as the Instagram generation finally provided the best audience for that contradiction of self-obsession and self-obliteration.

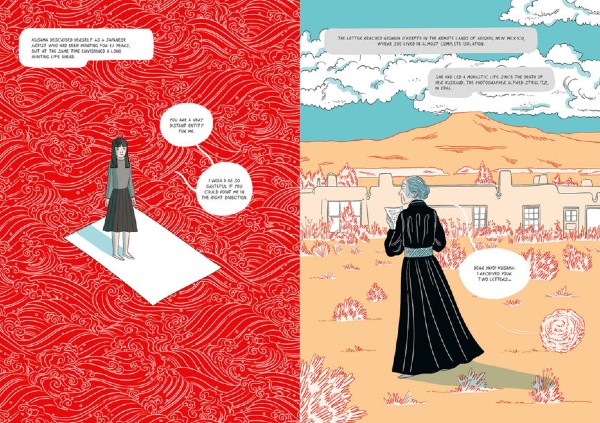

Macellari’s limited colour pallette is used so artfully that she doesn’t need gutters, her art often filling the page seamlessly, evoking the ‘infinite’ experience of being up close to one of Kusama’s infinity net paintings, or immersed in one of her installations. Her characters are simple but expressive, set within panels that alternate seamlessly between reality and metaphor, reflecting Kusama’s own art styles, while showcasing Macellari’s considerable skill and flair too. The combination of passive narration and story told through gesture and dialogue reminds me of Isabel Greenberg’s work – especially in speculative biography mode as in Glass Town. There is a little less room for interpretation in Kusama though, as the colours and visuals keep a firm grip on mood throughout the book. Even as Kusama herself loses grip on reality at times, Macellari’s book remains grounded, and a little inscrutable.

The other famous artists (Andy Warhol, Joseph Cornell) that appear in the biography are fleeting presences, reflecting how Kusama plays down their importance in her own account of her life, the exception in both cases being Georgia O’Keeffe. The American pioneer of close-up natural abstraction is treated to her own colour scheme, as we catch a glimpse into her sun-drenched, New Mexico retreat. The two artists exchanged letters when Kusama was still an art student in Japan, and it is truly, in my opinion, one of the great serendipitous relationships in the development of Modern Art. O’Keeffe encouraged the much younger woman to move to America and become part of the art scene, seeing her potential in their shared intensity of expression.

We see many faces and embodiments of the artist as she grows up through the book. My favourite is grumpy 1990s Kusama, finally being asked to exhibit at the 45th Venice Bienalle. Not quite yet the 2010s Kusama that we know, stern and whimsical, with the iconic bright red bob. She’s still here, working away.

Selfishly, I would have liked a little more varied perspective in this book, having already read the artist’s autobiography. It’s a fairly uncritical reflection on an artist that has definitely offended a few people over the years. That said, I would definitely recommend this as a jumping on point for someone who hasn’t read Infinity Net. The sex, politics, and mental health stuff is handled tastefully, and relatively shallowly too, making this a suitable read for teenagers. If you feel insufficiently destabilised by the experience of reading Kusama, perhaps try putting your face right inside the book and pouring your self into the pages. Naked, obviously. Or simply allow the mild delirium or insomnia induced by living through a pandemic to help you approach the right state of mind, and be inspired to produce some infinite dot paintings of your own.

You can buy Kusama direct from the publisher here, or from your favourite comics retailer.

Elisa Macellari (W/A) • Laurence King Publishing, £14.99

Review by Jenny Robins