A COMICA FESTIVAL TIE-IN!

I’m not sure many creators set out hoping to be a ‘cult’ success, but I guess there are worse places you could end up. British cartoonist Carol Swain seems to fit the definition precisely; despite an army of fiercely devoted fans among the cognoscenti, her work has never enjoyed the more widespread acclaim it deserves. However, as the graphic novel market seems at last to be emerging from its cocoon, it could finally be catching up with a creator who was ahead of her time.

With a background as a fine artist, Carol Swain extended her practice to comics in 1987, after attending a workshop held at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts. (Perhaps not surprisingly, the workshop – on the fringes of an exhibition entitled Comics Iconography – was partly organised by “Man at the Crossroads” Paul Gravett, who currently co-directs the Comica Festival.)

That heralded a prolific period of production, during which her pithy short stories appeared in both her self-published Way Out Strips and a range of domestic and international anthologies, making tracking down her work a frustrating treasure hunt. (Fortunately, Dark Horse have put out a nicely produced hardback collection, Crossing the Empty Quarter and Other Stories).

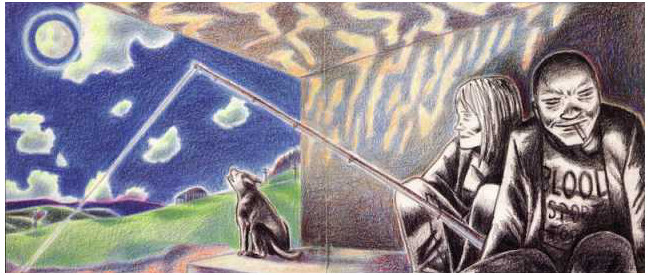

From her first strips, she established a unique signature in both her mark-making and narrative style: her work was characterised by the use of deeply textured charcoal, combined with an attention to frame composition, rhythm and progression that inevitably led some commentators to refer to it as ‘cinematic’.

Her subject matter also caught the attention. From her earliest strips, she takes us into the lives of characters who live in the edgelands, physically, socially, culturally or psychologically: the migrants coming up the River Thames in ‘Gallions Reach’; the nomadic trailer-park dwellers of the Ballardian ‘B-Movie’; the ‘Last Punk in Britain’, liberated from his cage at London Zoo by activists.

There’s not much overt politicising in Swain’s work, but it’s probably worth noting that her initial fusillade of work came out in the dog days of Thatcherism. With Britain’s first female prime minister notoriously stating in 1987 that “there is no such thing as society”, it was a time when exclusion was being written into law, through measures such as the notorious Section 28, which sought to ban the “promotion” of homosexuality, or the hated “poll tax”, which turned a citizen’s right to vote into a luxury shopping item.

(Although, ironically, both of these measures had the counter-productive effect of politicising whole new sections of society into resistance.)

The changing face of Way Out Strips:

(L-R) Self-published, Tragedy Strikes Press, Fantagraphics Books

After four self-published issues (1988-91) and three issues published in 1992 by Michel Vrana’s Tragedy Strikes Press, Way Out Strips moved to Fantagraphics, who published four issues between February and November 1994. These issues seemed to mark a transition in her work that sets up her later graphic novels, starting to develop longer narratives and moving away from the urban environments – especially London – that had dominated her work.

This shift is epitomised in ‘Samhain’, a 38-page story that ran across all four issues. Set in a small Welsh town, it features the return of a young woman who, reflecting Swain’s own experience, had moved to London – a provocative act to many in the British provinces, akin to betrayal or desertion. As in a lot of her work, it raises the question of belonging; Ruby is one of many characters in a liminal state, caught between the conflicting gravitational pulls of two places and two ways of life.

In the final issue of Way Out Strips, Fantagraphics promised that Swain’s next “collection of all-new stories” would be out the following May. However, it didn’t appear until early 1996, by which time it had coalesced into her first long-form (72pp) graphic novel.

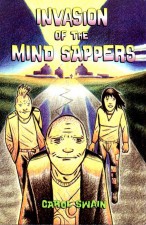

Invasion of the Mind Sappers marks the start of what could be called Swain’s “Llanparc trilogy”, set around a fictional village close to the physically invisible but historically and culturally fortified border between Wales and England.

Invasion of the Mind Sappers marks the start of what could be called Swain’s “Llanparc trilogy”, set around a fictional village close to the physically invisible but historically and culturally fortified border between Wales and England.

“Foodies” love nothing more than to laud the French concept of terroir: the notion that the characteristics of a region impart its produce with a very specific flavour. In a way, Swain’s later work has a similar ring: the topography and rhythms of the landscape becomes increasingly important, forming an immersive microcosm in which the characters play out their dramas.

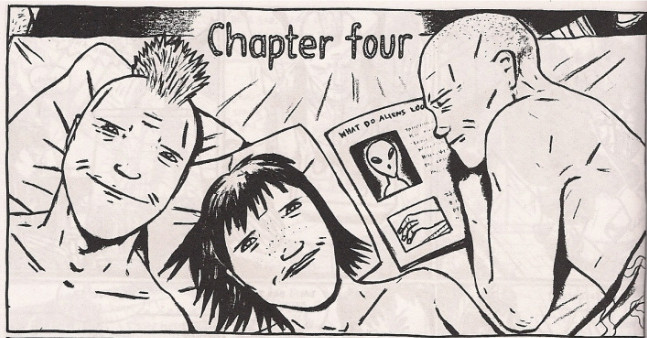

Mind Sappers features three classic Swain protagonists – anomic, alienated small-town kids, disengaged from school and the society beyond that it represents. Following a minor earthquake, they retreat into an imaginary world of UFOs and alien invasion as the only way to explain the strange behaviour of their recently arrived temporary head teacher.

Admittedly, the change of approach from her more poetic, oblique shorts to a longer, more structured narrative wasn’t entirely painless; the story veers towards the slightly overblown towards its climactic action. However, in finding a new form for her work and building on the evolution visible in ‘Samhain’, it marks a springboard for what is to come.

After that, we had to wait another eight years for Swain’s next book – Foodboy (Fantagraphics, 2004). Mostly narrated in flashback, the book represents Swain’s biggest structural experimentation so far, but it lands us back in familiar marginal territory.

After that, we had to wait another eight years for Swain’s next book – Foodboy (Fantagraphics, 2004). Mostly narrated in flashback, the book represents Swain’s biggest structural experimentation so far, but it lands us back in familiar marginal territory.

This time alienation takes a much more literal and extreme form, as a young man, Ross, withdraws further and further from society, becoming increasingly feral, silent and animalistic.

Events are seen through the eyes of Gareth – a life-long friend of Ross and the “foodboy” of the title. Despised by his Eastern European co-workers at the hotel where he’s employed as a kitchen hand, and with no apparent personal connections, we’re left wondering by the book’s enigmatic conclusion whether Gareth will – or even should – follow Ross into the wilds.

Although she collaborated with her partner Bruce Paley on his graphic autobiography, Giraffes in My Hair: A Rock ‘n’ Roll Life (Fantagraphics, 2009), Swain’s next piece of long-form fiction didn’t arrive until 2014. And while the publication of Crossing the Empty Quarter during that 10-year gap might have argued that her short stories remained her defining work, the arrival of Gast, again from Fantagraphics, refuted it decisively.

Longer than Mind Sappers and Foodboy combined, it represents stylistic continuity with its predecessors while also stepping out into new territory. At its heart is Helen, a solitary and introverted 11-year-old girl who has moved to Llanparc with her family.

Longer than Mind Sappers and Foodboy combined, it represents stylistic continuity with its predecessors while also stepping out into new territory. At its heart is Helen, a solitary and introverted 11-year-old girl who has moved to Llanparc with her family.

Spending most of her time wandering the area and observing the local wildlife, she becomes intrigued when she hears about the death of a “rare bird” at a neighbouring farm. As Helen throws herself in to her investigation, with the unexpected assistance of some locals, she begins to piece together the unorthodox life of a mysterious local farmer.

In one of the most eagerly awaited and rewarding graphic novels to have been published so far this year (which we reviewed here), Swain takes us into a subtle and oblique study of her young protagonist – another character in the transitional zone between the innocence of childhood and the experience of adulthood.

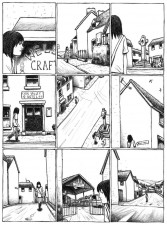

A sequence from Gast

And while Swain’s artwork is still uniquely styled, her line and mastery of shading seem to have become finer. She also uses the increased page count to explore more thoroughly – along with Helen – the environment in which the story takes place, subtly interweaving themes as diverse as transgenderism, animal welfare and the precarious state of the rural economy.

It’s hard to capture in words the richness, mystery and pleasure to be gleaned from the work of Carol Swain. Let’s hope that her re-emergence into a comics market that might finally have caught up with her will propel her out of the twilight world of ‘cult’ success and towards the profile that her mesmeric work deserves.

Carol Swain will be talking about her work on the Cult Comics Comica Conversation panel (in association with Broken Frontier) on November 7th. For booking details visit the Comica site here.