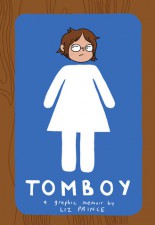

Liz Prince’s Tomboy should be required reading for all school groups. It’s a fantastic, witty and touching story about identity, growing up, finding your place and what it actually means to be a girl.

The autobiographical story of self-proclaimed tomboy Liz Prince deals with middle school, high school, parents, bullies, punks, friendship and romance in a story that will speak volumes to any non-girly girl.

This is Prince’s first graphic novel, published by Zest Books, and it’s a strong debut. However, she’s been published in many anthologies and has released a few shorter comics of her own – some of which can be found on her website.

I was delighted to get the chance to interview her and find out more about the ideas behind her marvellous graphic novel.

Your graphic novel Tomboy is about your youth, growing up as a non-girly girl and coming to terms with your own identity. What made you decide to write your own story as a graphic novel and did you find it strange to see yourself on the page?

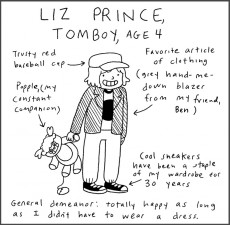

I have been drawing comics about myself since high school in 1996, so I don’t even find it strange to see myself on the page: it’s where I’m most comfortable!

Comics are the way I communicate best, and since I’ve been drawing them pretty much exclusively for 18 years, a graphic novel was the only way I would – or could – choose to tell this story.

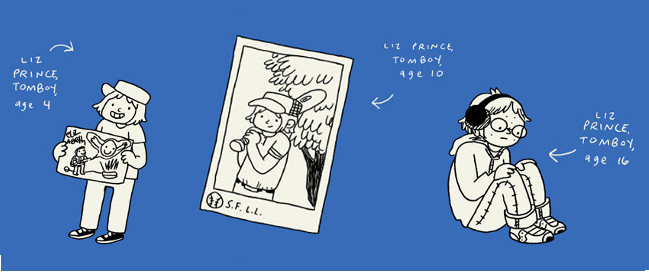

Much of the format of your book is an older you reflecting on the adventures (and misadventures) of your younger self. Did looking back and drawing memories from your childhood cause you to take a different perspective on any of the events or people you wrote about?

I hope that people realise that memoirs are fractured versions of the truth, because when one person writes about their experience, it will always be in their voice, with their memories, which can shift and change over time.

It was interesting to go back through my early childhood with the understanding that I have now of gender fluidity: some of the things that I did I want to hug myself for (not being willing to change who I was to fit in) and some of the things I want to strangle myself for (hating girls for being girls, because it added pressure for me to fit in).

How accurate did you feel you had to be when writing this story? Did you stay very true to life or take the artistic liberty to make a few alterations?

I took a lot of artistic liberties in terms of characters. Most characters are really two or three people combined into one, because I was interacting with a lot of people on a daily basis, but it would be too laborious for a reader to have to juggle a lot of incidental characters in a book this short, and really, a lot of these characters were secondary friends, or school acquaintances anyway, who would only be introduced to say one line.

And the trappings of memory are such that I can’t really remember WHEN a specific incident happened, I can just remember who was involved, and maybe where it happened, so using those clues, I’ve tried to get the continuity correct, but I wasn’t adhering to it like martial law.

Your book is a very relatable story for any young people who’ve felt out of place growing up (which is nearly everyone ever!) What message do you think Tomboy is trying to send to those people who do strongly relate to this book?

It’s my hope that Tomboy helps them feel dedicated to who they are, even if they don’t fit in with the “normal kids”, and I hope that “normal kids” who read the book will feel a new affinity for the kids who are “different”.

Your book is always very funny and takes a humorous look at very awkward, embarrassing or even painful moments of your childhood. How did you feel looking back at these things? Do you think writing this graphic novel forced you to look back more honestly or clearly at some of those memories?

Your book is always very funny and takes a humorous look at very awkward, embarrassing or even painful moments of your childhood. How did you feel looking back at these things? Do you think writing this graphic novel forced you to look back more honestly or clearly at some of those memories?

Thanks! I’ve always tried to use humour to disarm uncomfortable situations, and I think humour is a great tool for understanding. Some of the things that I wrote about in Tomboy were painful to remember, and a lot of those memories were more about feelings than they were about the incident that was portrayed.

I don’t think writing this book forced me to look more honestly at those things, because I tend to be pretty honest with myself, even when it’s harsh, but it forced me to look beyond those things, to what could have been going on outside of me to cause some of the strife.

You talk a lot about gender identity and a little about discovering feminism in the pages of your book. Would you describe yourself as a feminist? And if so, what does feminism mean for you?

This is the million dollar question: yes, I consider myself a feminist, but it took a lot of time to get there. What Tomboy really only touches on is internalised misogyny, and it’s a subject that I’d like to come back to and write more about at some point.

It was hard for me to identify as a feminist because there is so much anti-feminism propaganda, as well as anti-PC backlash that paints anyone who has a politically motivated agenda as a “killjoy” and I have never wanted to be a killjoy: I’m the one who’s always cracking jokes!

I really didn’t like girls for a long time, and even after discovering punk and becoming OK with being the kind of girl that I was, I was still doing a lot of “othering”, in which I’d be like “well, punk girls are cool, but other girls still aren’t”.

I think that’s actually a pretty normal thing; we have our preferences, our things that we like and identify with, and there are other things that we’re hyper-critical of, and I think there is still a lot of othering that goes on, even within feminism itself, between tactics and ideals. I mean, it’s a movement, and it’s going to include a wide range of differently thinking people, all (hopefully) trying to achieve the same thing, but using different methods to get there.

Mostly I didn’t identify as a feminist until recently because I thought there was some process you had to go through: I don’t know a lot of the history of the feminist movement, and I thought that in order to identify, you had to do your research.

I’ve been hesitant to label myself as anything, especially punk, because what that means to different people varies so much: there are people who would come up to me in a heartbeat and tell me I’m not punk, even though it’s the scene and music that I identify with, and the community that I’m most active in. And I felt the same way about feminism, and that people will probably come up to me and tell me I’m not a feminist, but I’ve realised that what that means to me is just personally more important than what that means to someone else.

In your book you say that when you were growing up you didn’t want to be seen as a girl, because being a girl meant being weak or superficial. Why do you think you thought that way and how have your views of what it means to be a girl changed since then?

In your book you say that when you were growing up you didn’t want to be seen as a girl, because being a girl meant being weak or superficial. Why do you think you thought that way and how have your views of what it means to be a girl changed since then?

I hope I outline it pretty well in the book, but it was a combination of the fact that I didn’t like “girly” things (ugh, I actually really hate that term “girly”, but, I don’t know what to put in its place. Oh, I guess I hate it because “girly” had a negative connotation to me, something else to explore). There was also the fact that a lot of outside forces were trying to tell me that I was supposed to like those things.

It’s also because of the attitude that boys and men have about girls: that they’re supposed to be submissive and protected, that we’re fragile. I know it seems like a kid can’t pick up on those nuances, but obviously we do, from very early on. I’ve been doing a lot of personal work on myself not to be dismissive of things that seem more feminine, and I definitely don’t feel limited by what I or other women can accomplish. I do still feel limited by how women are “supposed to be” and how American society reinforces that.

What advice would you give for girls who aren’t your stereotypical “girly girl” growing up?

I think that a lot of my hatred towards girls was motivated by the fact that I personally couldn’t believe that ANYONE actually wanted to be a girl: I felt like it was all imposed by society. That was why it always stung so much when a previously tomboyish friend would suddenly “go girl” on me: because I felt like they had given up who they really were, and just decided to fit in, because it’s easier.

I’m able to see that, obviously, people are able to go through many phases and none of it is necessarily a show, but there are things that people will sacrifice in order to fly under the radar. I hope that my fellow tomboys will feel comfortable in whatever path they choose: whether it is my tomboy-for-life status or a tendency to be more feminine or fully genderqueer or trans or whatever. You really aren’t limited to one way of being.

Your book ends with you coming to terms with being a tomboy in a positive light. Is that still how you feel now? Would you still describe yourself as a tomboy?

Your book ends with you coming to terms with being a tomboy in a positive light. Is that still how you feel now? Would you still describe yourself as a tomboy?

I still describe myself as a tomboy, even though tomboy feels like a term for a young child. I have been told that I am genderqueer by others, but I don’t identify as that, because I am still a cis-female, and also because of that previously stated unease at labeling myself.

Also, it’s all just labels. But I have been kind of interested in some people’s disappointment in this book that it turns out that I’m not gay and I’m not trans, and that to me feels like another aspect of the gender stereotyping: that anyone who isn’t gender conforming must be non-conforming sexually or otherwise. I hope that I continue to participate in interesting dialogues about gender because of this book.

What are your plans now; do you want to write another graphic novel? If you did, what would you write about?

I do have another graphic novel that I want to write, but I’m not ready to state publicly what that is. I hope to start it by the end of the year. I’m also planning on drawing a short comic that could be considered an excerpt from Tomboy: it’s a scene that never made it into any of the drafts, but it’s one that I see as a good companion to the book. I plan to self-publish that.

Tomboy is available from Zest Books in September 2014. You can pre-order the graphic novel here, and find more of Liz Prince’s work on her website here.

Great interview!

[…] Tomboy by Liz Prince […]