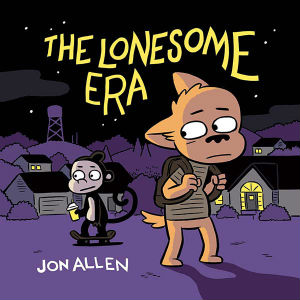

Jon Allen has been quietly working away at his Ohio Is For Sale series for years now. While the series’ first collection showcased his eye for finding the dark comedy in the lives of small town washouts, The Lonesome Era is a more focused and emotionally resonant work. The book serves as a coming-of-age story for metal-head skateboarder Camden as he grapples with both his closeted homosexuality and his secret crush on his best friend Jeremiah. Though the story is told through Allen’s sparse funny animal comics style, it is his masterful choices in pacing and detail that fully drives home the prevailing loneliness and aimless alienation of growing up different in a small town during the middle part of the ’90s. By being so non-nostalgically anchored in that time and that place, The Lonesome Era allows the younger reader to bridge the decades and recognize the eternal human need to be loved and accepted, while collapsing time for the older reader to let them recall their own teenage isolation.

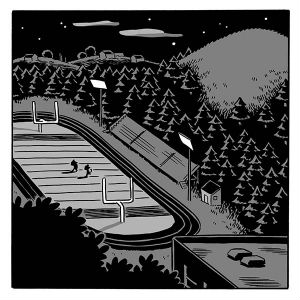

Allen lets the tensions of The Lonesome Era slowly simmer as he takes us through the small suburban lives of dog-boy Camden and his best friend monkey-boy Jeremiah. We see them stargazing and awkwardly tussling on an empty football field; an overly long moment where Camden has Jeremiah pinned to the ground cluing the reader into his unspoken desires. The pair engage in teenage hijinks, like harassing the drive-through speaker and going to a Death Metal concert at the local VFW Hall. When the flamboyant bunny boy behind band Carnosphere’s merchandise table flirtingly asks if Jeremiah is Camden’s boyfriend the interaction catches him off guard in a way that reveals his unease about his sexuality. Any potential for further flirtation is ended when Jeremiah wanders over and vomits up the two hot dogs he had found on the floor. Camden then steals a band shirt and skates away, only to break his leg going down a set of stairs.

Allen lets the tensions of The Lonesome Era slowly simmer as he takes us through the small suburban lives of dog-boy Camden and his best friend monkey-boy Jeremiah. We see them stargazing and awkwardly tussling on an empty football field; an overly long moment where Camden has Jeremiah pinned to the ground cluing the reader into his unspoken desires. The pair engage in teenage hijinks, like harassing the drive-through speaker and going to a Death Metal concert at the local VFW Hall. When the flamboyant bunny boy behind band Carnosphere’s merchandise table flirtingly asks if Jeremiah is Camden’s boyfriend the interaction catches him off guard in a way that reveals his unease about his sexuality. Any potential for further flirtation is ended when Jeremiah wanders over and vomits up the two hot dogs he had found on the floor. Camden then steals a band shirt and skates away, only to break his leg going down a set of stairs.

Camden’s broken leg allows the plot to slow down even further to let the reader fully inhabit life in Piney Bluff. Allen methodically takes the reader through Camden’s older sister Veronika searching for a book to bring to him at the hospital and uncovering a journal confessing his crush on Jeremiah. Her muted response to this discovery then matched by the nonchalant bedside manner of Dr. Poptarts as she discusses another skateboarding accident in which a patient’s testicles exploded to Camden. This deadpan comedy approach to heavier subjects, also seen in the patient calmly siting in the waiting room with a knife sticking out of his head, does much to establish the tone. Camden’s life in Piney Bluff is as dry and flat as Allen’s sense of humor. His tiny place within the world further reinforced by Allen’s usage of a disconnected wandering camera that floats between Camden, Veronika, and other ER patients, which then travels outside of the hospital zooming out to take in the silent cookie cutter houses of the town.

The narrow borders of Camden’s world inform why he is so heavily invested in his crush on Jeremiah. When the duo listens to a Corpse Blizzard CD in Camden’s bedroom it is a reminder of how in a pre-online world sharing the small bits of culture available to you with a friend was an intensely bonding experience. All evidence points to both boys having no other close friendships so that while Camden’s closeted sexuality makes him a de facto outsider, Jeremiah is clearly no more socially accepted. The boys have to stick together to defend themselves against their tormentors because there appears to be no one else who will. Because of this Camden is wracked with guilt when he fails to protect Jeremiah from a gang of bullies due to his injured leg. Luckily when the pair, in typical teenage boy fashion, get too high smoking weed out of dollar bills in and abandoned factory, Camden will reverse his earlier cowardice. It is both a touching and very real moment as the pair celebrates the day’s victory by drinking Slurpees outside of a 7-11. Yet a hug given in camaraderie is far more loaded for Camden than it does for Jeremiah.

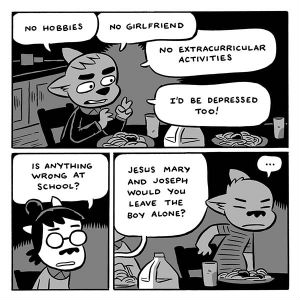

Camden will eventually be pushed to his unrequited breaking point by an uncomfortable interaction with an overly flirtatious girl awkwardly trying to make out with him. After this incident while drinking siphoned liquor and playing video games in Jeremiah’s basement Camden plants a kiss on his passed out friend. Running away from the startled Jeremiah in shame, Camden is distracted and overwhelmed at school the next day, distancing himself from his best friend and fighting with his family over dinner. Which leads to the climax of the book where Camden has to confront the effects of trying to hide his sexuality not only from himself but those closest to him.

Allen does a fantastic job throughout the book at getting the reader to feel Camden’s inner turmoil through a multitude of small details. It’s the family dinner of spaghetti and meatballs served with a whole glass of milk and Camden’s father blaming his surly behavior on video games, heavy metal and a lack of a girlfriend that subtly remind the reader of the conservative cultural climate he has grown up in. It’s the way Jeremiah casually calls the quadratic formula “gay” or the taunts of the bullies that recall how much less acceptable homosexuality was even twenty years ago. Allen’s frequent cutaways to the rusted-out factory, the rows of tract housing, the near vacant park, or the shabby hospital waiting room not only give a sense of place, but in their stillness and vacancy parallel how alone Camden must be with his secret. The way Allen slowly unfurls conversations with almost every line given a change in framing and performance attunes the reader to the rhythms of conversation between Camden and Jeremiah in a way that makes it hard not to feel how charged these exchanges are for Camden.

Stylistically there is an excellent juxtaposition between the exaggerated goofiness of Allen’s animal characters and the gravity of their world. A prime example is the way Allen’s cartooning captures the comic ridiculousness and pathetic desperation of freckled gapped-toothed country gal Sam and her plan to get Camden alone in the woods for a make-out session. Her design, dialogue, performance, and the cutaways to Ladies Night Country Hits on the floor of her car all show without telling so much about life in Piney Bluff. The way the Allen’s coloring favors large patches of black and grey with only occasional highlight of white even in daytime, further enforcing the stifling small town air.

In presenting both a world and a friendship that feels so lived in, The Lonesome Era side steps any of the after school special tropes that young adult fiction can find itself guilty of. Nothing ever feels trite or forced about Camden’s experience despite some of its archetypal underpinnings. The reader comes to care about Camden and want the best for him not just because of the difficult position his sexuality puts him in, but because we have spent enough time just hanging out to feel genuinely close to him. Allen’s greatest strength as a storyteller and a cartoonist is his confidence in trusting the audience to linger in the grey quiet of Piney Bluff, allowing us to infer so much about the unspoken anxiety of its residents’ lives. It fosters an intimacy that makes this story about funny cartoon animals deeply human.

Jon Allen (W/A) • Iron Circus Comics, $30.00

Review by Robin Enrico

[…] looms ever closer. How much longer can this go on?” You’ll find out! Check out this extensive preview […]