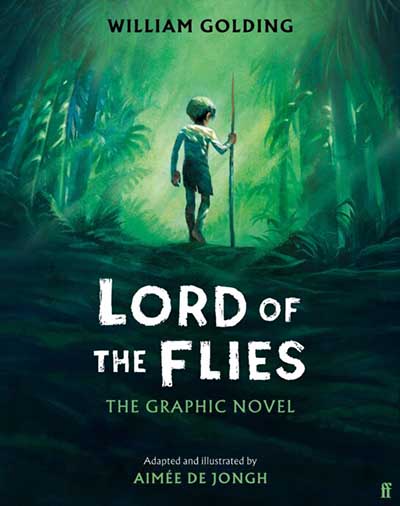

Harsh, chaotic and honest. These are all words that come to mind when thinking of William Golding’s literary masterpiece Lord of the Flies. With heavy themes about morality at its core, this classic is not a book that is easy to adapt, which is perhaps why Aimée de Jongh and Faber are the first to craft a graphic novel adaptation.

Before diving in, a little context for those who haven’t studied or read this masterpiece. Lord of the Flies begins amid a wartime evacuation with a plane crash landing on a deserted island. The only survivors? A group of school boys. Soon realising that help won’t be coming for a long time, our protagonist, Ralph, commands authority over the other boys, establishing a semblance of order. However, this soon deteriorates when many of the boys grow tiresome and paranoid, with the group splitting. Without civility, the boys soon give in to their basest instinct; hunt or be hunted. At the centre of their paranoia is the ever-lurking enigma of ‘the beast’, a monster who is entirely imaginary, but becomes more and more real to the children, resulting in their ritualistic offering of a decapitated pig head – an image which often comes to mind in association with Lord of the Flies, due to its prevalence on various publication’s book covers.

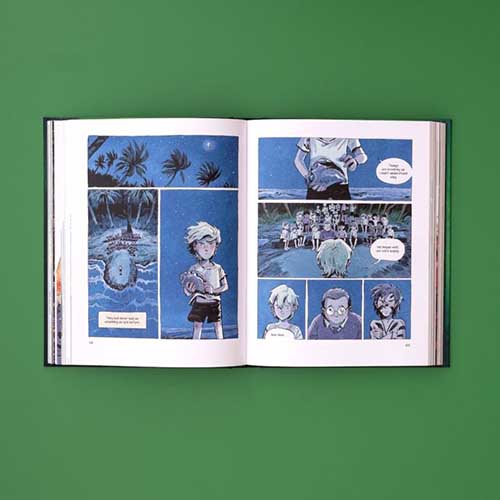

Law and order. Would we return to our primitive nature without it? Where would children be without any adult guidance? Ralph is a mere twelve years old when he crash-lands on a deserted island, and his age is wonderfully rendered through de Jongh’s initial illustrations, through which she showcases the childlike innocence that breaks through a very traumatic situation. Dirty and messy from the crash, Ralph’s eyes nonetheless light up at the sight of tropical fish, his laughter echoes as he splashes happily in the sea, and he ‘yahoos’ at the prospect of there being no grown-ups. After encountering the more serious ‘Piggy’, a bespectacled, quiet child, they summon any survivors by using a beautiful conch shell they find in the ocean.

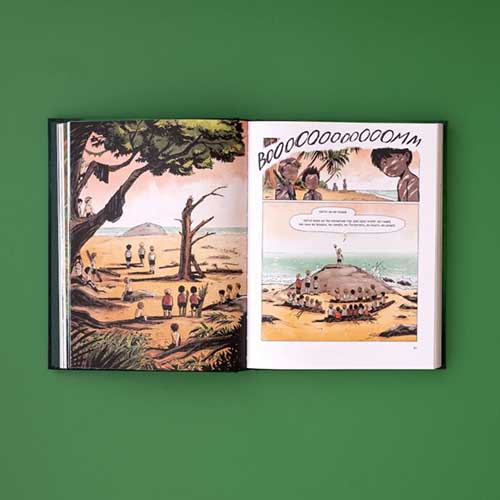

Under Ralph’s guidance, the boys initially work together well, and life on the island seems idyllic, supported by the calming orange and pink hues. However, the inevitable downfall of their constructed society comes swiftly at the mere mention of the beast. The title Lord of the Flies was no mere coincidence on Golding’s part – this is a literal translation of Beelzebub, a demon from the bible embodying pride and warfare – themes that have major ramifications throughout the entire novel. Terrifying and all-consuming, de Jongh visually represents the beast, himself an allusion to Beelzebub, perfectly – a giant, alien, cobra-type creature with glowing eyes and gleaming fangs.

Using their quest for food as an excuse, Ralph’s nemesis Jack and his crew literally disguise themselves with mud on their faces to capture their prey, but soon figuratively mask themselves from the civilised rules of society: “The mask was a thing of its own, behind which Jack hid… liberated from shame and self-consciousness.” Themes of mob mentality, savagery and groupthink are all explored in the panels that follow, one of the more sinister examples being the obvious comparison between Jack’s blood-thirsty desire for pig meat and Piggy’s nickname. This makes the reader question how far Jack and his cronies will really go, and de Jongh capitalises on this fear, just by the subtle ways you catch Jack looking at Piggy; like a hunter would look at his prey. The realisation that there are suddenly no consequences marks the end of order and the beginning of barbarism – a subtle change, marked neatly by the animal-like tearing and swallowing of the cooked pig Jack hunted, as the softness of the day transitions into gloomy night.

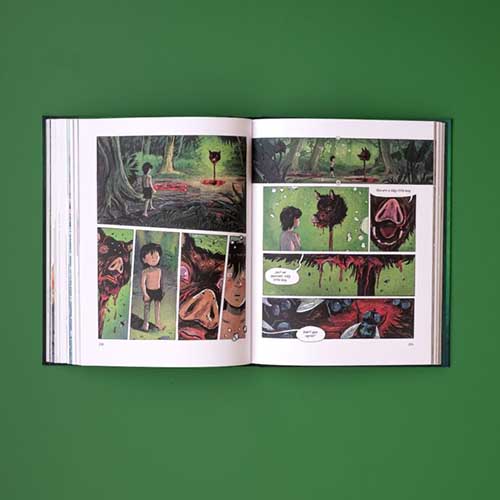

The scene I was most dreading visually was that of the famous pig’s head. But I was also intrigued as to how de Jongh would depict Simon’s psychedelic conversation with ‘the beast’ (using the pig as a vessel). The scene was visually quite gory, with plenty of blood and guts to really hammer home how vicious the children have become. Simon’s delusion of conversation with the beast makes use of this, with deep reds enveloping the young boy, hundreds of flies feasting on flesh and the pig’s head becoming larger and more terrifying as it dwarfs him, consuming him in its blood-drooling mouth. It is morbid, terrifying and ingenious, and the duality of human nature and penchant for right and wrong is further explored in Simon’s attempts to warn the other boys about what he has learned.

De Jongh’s aim when adapting Lord of the Flies was to keep the original story intact whilst adding “meaning through composition, colour and atmosphere”, and she has absolutely achieved that goal over and over. I loved how she used artistic licence to expand on the already rich source material; while the text is directly lifted from the original book, whether it’s wordless panels of Ralph’s brightly lit dreams or how Simon is briefly mistaken for a monster, she expands on the well-known characters without changing or deviating from the original. Lovers of the classic, or even those who may find the original intimidating, will absolutely appreciate de Jongh’s excellent reinterpretation.

William Golding and Aimée de Jongh (W), Aimée de Jongh (A) • Faber, £20.00

Review by Lydia Turner

Faber and Gosh! Comics present ‘Lord of the Flies at Seventy’ on Wednesday September 18th – a talk with Aimée de Jongh and Judy Golding at the Bindery in London. More details here.