Locust Moon Press leapt onto the radar screens of fans and critics alike with their critically acclaimed oversized anthology celebrating Winsor McCay’s seminal creation Little Nemo. The publisher’s ambitious 144-page, 16″ x 21″ hardcover, Little Nemo: Dream a Little Dream, absolutely smashed their Kickstarter crowdfunding goal and would go on to clean up at both the Eisners and the Harveys.

Locust Moon’s latest project was funded on Kickstarter within days – an accomplishment that’s becoming something of a trend for the publisher. At the very least, it demonstrates that their focus on the history of the graphic narrative resonates with scores of discerning fans.

Locust Moon’s latest project was funded on Kickstarter within days – an accomplishment that’s becoming something of a trend for the publisher. At the very least, it demonstrates that their focus on the history of the graphic narrative resonates with scores of discerning fans.

While not as physically or logistically massive as their award-winning anthology, The Lost Work of Will Eisner – an archival collection of work produced by Eisner as a teenager – may just eclipse it in terms of its historical importance to the medium. Culled from previously lost publishing plates discovered by art collector Joe Getsinger, the book showcases the burgeoning genius of a future master of the form.

Locust Moon’s publisher Josh O’Neill graciously chatted with BF via email to discuss the historical importance of the press’s first archival project and the urgent need for the preservation of comics masterworks.

BROKEN FRONTIER: The press release you sent out regarding the Kickstarter goes into a little detail about who found the plates and how, but doesn’t go into how they ended up at Locust Moon. How did you come to be the publisher of this project?

JOSH O’NEILL: We have a customer at the shop named Rich Greene – he’s buddies with Joe Getsinger. He told us that Joe had acquired this stuff, which, as he described it, honestly sounded too good to be true. So we basically dropped everything and immediately sprinted to Collingswood and stormed into Joe’s studio, demanding to see these plates.

Not only was the Eisner stuff exactly as described, there were many thousands more, including some Kirby stuff. It’s just a mind-boggling collection. We knew the instant we saw these strips that we wanted to publish them. Now, a couple years later, we’re almost ready to go to print.

How does it feel to be a part of such an important piece of comics history?

We’re just honored to be entrusted, by Joe and by the Eisner estate, with being the ones to present this material to the world. We’re doing everything we can to treat it with the respect it deserves.

Will Eisner’s work means so much to us – this whole project is in service to his memory. I think seeing how his vision first came together has a really beautifully illuminating and humanizing quality. I think people who read this book will end up with a slightly different, richer view of Eisner. And we couldn’t be any prouder to be doing our part to expand his legacy.

This is our first archival project, but not our last. Comics are such a young medium still, but we’re just now reaching the point where its origins are starting to fall irretrievably into the past. Newspapers disintegrate, people get old and pass away; there’s nobody left to interview about Eisner’s teenage years.

If we had been able to do this project twenty years ago, we would have been able to gather a stronger historical context for it. I think it’s a really important time for projects like this, to fill in some vital gaps before they disappear for good.

What do think readers will be most surprised about, when they see Eisner’s early work?

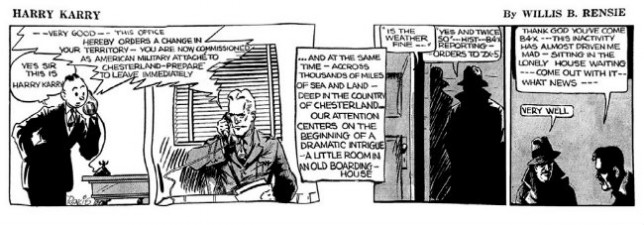

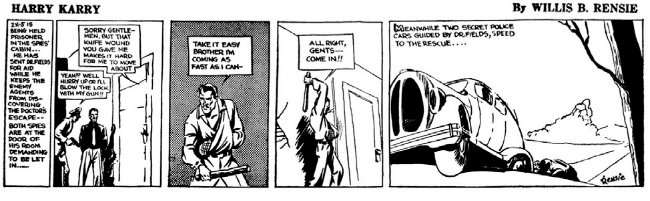

The versatility of it is both incredibly impressive, coming from a teenage kid, and also in many ways something Eisner had to overcome. One of the most intriguing aspects of this book is how transparently you can see him aping people like E.C. Segar and Alex Raymond, leaping from style to style, trying to figure out how he wants to draw.

We like to think of great artists as having strong internal visions that made them who they were – and Eisner by his early twenties was already a totally singular and transformative presence in American comics. But he figured out that voice through a process of imitation.

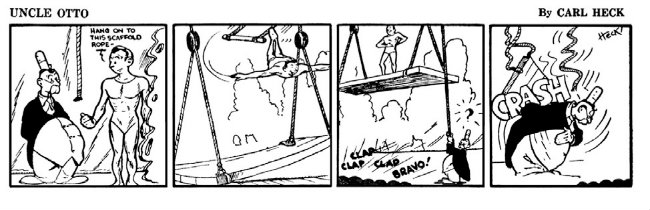

It’s also wonderful to see how free he is, even within the strictures of these fairly derivative comics. After ten Harry Karry strips he seems to get bored with the style and storyline, so he completely shifts gears smack dab in the middle of a strip: after panel 1 there’s a caption that says that Harry was called away on another mission, and suddenly the action shifts to another country completely and a brand new, pretty much completely unrelated story in a vastly different art style. You can just feel Eisner’s pleasure in getting to chart his own course and experiment with this stuff to his heart’s content.

On the Kickstarter page you note this project will be the first in a line of archival works published by Locust Moon. Can you expand a bit on the scope of this archival line – that is, what artists/publishers/periods would you like to shine a spotlight on next?

The next one is an art book and biography of the early 20th-century artist Herbert Crowley. He was an occasional cartoonist for the New York Herald, as well a painter, sculptor, musician, close associate of CG Jung, and general all-around weirdo visionary.

He worked in a variety of styles and media and created these gorgeous, eerie, otherworldly symbolist pieces ages ahead of their time, predicting the work of people like Charles Addams, Edward Gorey and Jim Woodring.

Crowley is a perfect example of somebody who’s falling irretrievably into the memory hole… he’s almost completely unknown at this point in time. Outside of a very short series of strips he did for the Herald, none of his work has ever been collected anywhere. It blows your mind to look at his art and know that it was stuff that was done from the teens through the thirties. He was channeling some powerful forces in his work, and they come through as clearly today as they did a century ago.

That book should hit shelves in 2017. I’m also researching a collection of Denis Kitchen’s illustrated letters… beautiful hand-written mail from people like [Robert] Crumb, Eisner, [Harvey] Kurtzman, [Art] Spiegelman, S. Clay Wilson, Al Capp, Alex Toth and many more.

There are a lot more possibilities. It’s a little distressing how many great artists have fallen by the historical wayside, but it creates a lot of opportunities for the great books necessary to resurrect them.