Around 1188, Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi wrote a poem in Arabic, based on seventh-century poet Qays ibn al-Mulawwah and his lover Layla bint Mahdi, which grew to become one of the most popular romantic tales in Arabic literature. Retold and reinterpreted in Persian, Dari, Urdu, Hindi, and other languages across the Middle East and Asia, it eventually trickled down into the Western consciousness with a little help from rock star Eric Clapton’s ‘Layla’, a song about his own unrequited love.

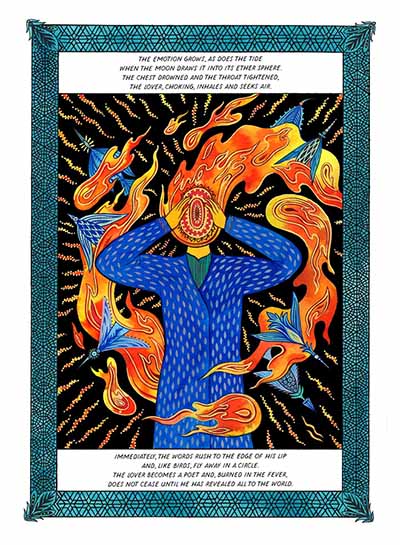

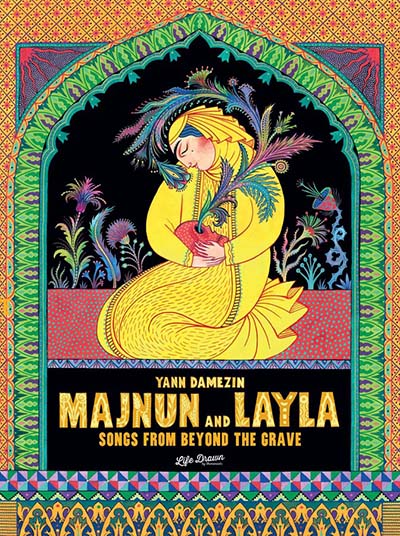

In 2022, artist and illustrator Yann Damezin published his own version in France, now translated for the English-speaking world. It is an undeniably beautiful book, marked not only by Damezin’s professed interest in Persian iconography, but by his decision to use art to draw out the gender inequality at the heart of Majnun’s relationship with Layla.

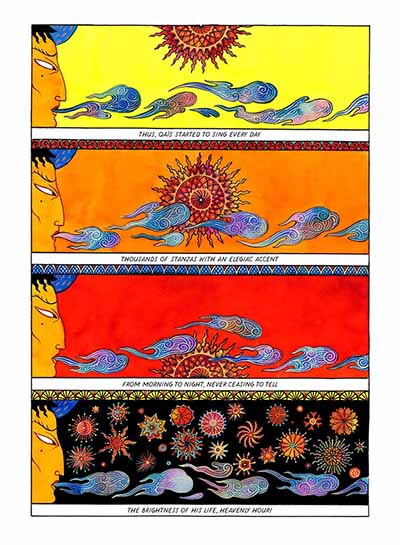

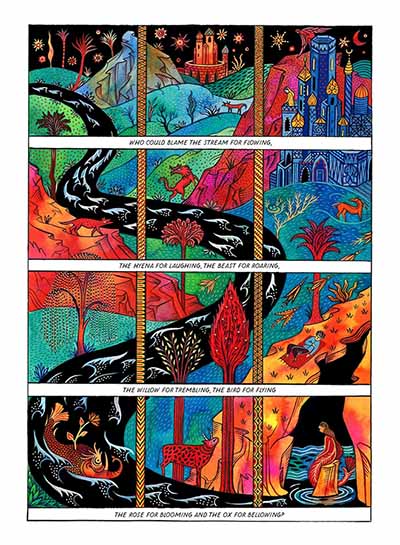

On the surface, the poem moves in a linear manner, beginning with Majnun’s love for Layla, and her father’s refusal to give her away to a man perceived to be insane, then ending with the paths taken by each thwarted lover as a fallout of that decision. “Becoming mad with love is a man’s privilege,” says Layla, flipping the traditional perspective that makes Majnun’s loss of reason more worthy of pity than the choice she is compelled to make. By focusing on the debilitating effects of patriarchy, Damezin does what every adaptation of a classic ought to, which is making it relevant for a contemporary audience. It also alludes to tropes that recur in Ganjavi’s other work, such as the love story of Shirin and Khosrow that also focuses on passion, unfulfilled longing, and erotic abandon.

There are a few hiccups, primarily when it comes to the language in translation that doesn’t always complement the art. Where Damezin favours a style heavy in symbolism, the prose tends to be almost literal, stumbling over clumsy descriptions such as the stanza describing Layla’s beauty: ‘Lips of ruby and a face like the moon / Hills for breasts, a vale in the hollow of her loins.’

That said, these lines almost fade into insignificance beside the gorgeous panels surrounding them. Looking for art inspired by the poem can take one down several rabbit holes but is an exercise that ultimately helps one appreciate Damezin’s approach. One can spot the influence of mid-18th century oil paintings of these lovers from Iran, or watercolours from the Ottoman period that must have appeared a couple of centuries after the poem. There are also echoes of examples from the royal cities of Tabriz and Herat at the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, as well as court paintings from Turkey and India that continued to appear over the following centuries.

Another nice thing about the book, apart from its glossary, is the afterword by Aqsa Ijaz and Thomas Harrison that sheds light not only on the poem’s origins but on some of Damezin’s choices. It explains why he grants Layla great verbal power, for instance, and how we are compelled to experience the story from her point of view as a counterproposal to more conventional interpretations that lean towards Majnun’s ‘endless singing’.

Adaptations don’t always work, fraught as they are with the weight of expectation as well as the need for unlearning what we think we know about them. This is a great example of how important they are when they work, and Yann Damezin deserves all the accolades that have come his way.

Yann Damezin (W/A), Thomas Harrison & Aqsa Ijaz (T) • Life Drawn, $39.99

Review by Lindsay Pereira