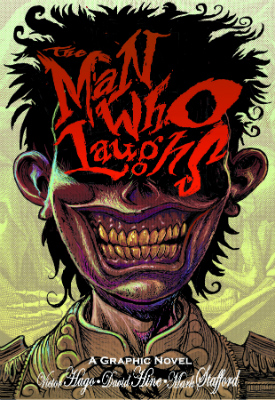

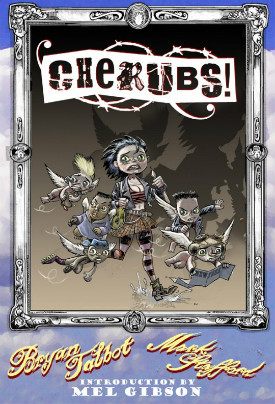

Mark Stafford has built up a reputation in UK comics in recent years for visual storytelling that is eerily macabre in tone and atmosphere. A frequent collaborator with David Hine on books like The Man Who Laughs for SelfMadeHero and The Bad Bad Place strip for Soaring Penguin Press, he has also contributed to Ravi Thornton’s HOAX Psychosis Blues and illustrated Cherubs! for industry legend Bryan Talbot.

Stafford is also the Cartoonist-in-Residence at London’s Cartoon Museum. We speak to Mark today about his influences, his career to date and the work of the Cartoon Museum in showcasing the rich history of the form…

Mark Stafford is contributing to the Broken Frontier Anthology, created to celebrate the magic of creator-owned comics. Check our Kickstarter campaign and please share it with your friends on social media using #BFanthology.

You’ve become well known in recent years for your collaborations with David Hine – beginning with SelfMadeHero’s first Lovecraft anthology – but could we begin with a brief overview of your comics career to date?

You’ve become well known in recent years for your collaborations with David Hine – beginning with SelfMadeHero’s first Lovecraft anthology – but could we begin with a brief overview of your comics career to date?

I moved to London from Bournemouth in 1990 to do a graphic design HND that I never completed, after which I drifted about a bit, wanting to be an illustrator and cartoonist, largely clueless about how to go about it, and drawing pages no bugger saw, until Paul Gravett pushed me in the direction of the now defunct Comics Creators Guild, where I met the right people and started getting pages into small press anthologies, and art onto walls.

With help I made some books of my own (Botulism Banquet, Scenes from Books I have not Read, Coin) and built up a body of largely unpaid stuff that I would periodically show to Bryan Talbot in a bar somewhere at two in the morning. He liked it enough to offer me Cherubs! when the chance came up, which, eventually, got me into a proper book, and the Cartoon Museum thing happened as well, around the time of Bryan’s offer. It’s all grown, haphazardly, from there.

Looking back over your work it’s clear just how versatile and adaptable an artist you are but I think it’s fair to say you’ve gravitated towards projects with eerier or more unsettling narratives. Are the themes of darker genre fiction the ones that most intrigue you as a visual storyteller?

I think it’s where my sense of humour gravitates to, and the rest follows. I’m drawn towards the horror genre, but I’m less interested in the big ‘reveal’ moments and all the supernatural flummery than the earlier scenes, where things just start to go off kilter, and people’s everyday lives take a strange turn. I love trying to capture that feeling, which tends to lend itself to the shadows and troubled expressions and iffy perspectives which I’m rather partial to drawing. I can draw ‘cute’, but it’s an odd kind of cute. I’m not interested in heroes or idealised characters. I’m all about the doubt. Though I might draw a romance, sometime, to prove myself wrong.

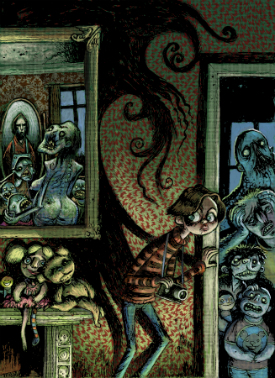

Sample pages from Hine and Stafford’s ‘The Man Who Laughs’, ‘The Colour Out of Time’ and ‘The Bad Bad Place’

Given the gloriously grotesque appeal of your style who would you count as the foremost influences on your approach to the comics page?

I tend to think that style isn’t something you should aim for, rather, it’s something you end up with. There’s kind of a war in my head between the more ‘realistic’ cartoonists I loved as a teenager, who tried to create a three dimensional world (Bolland, Corben, Moebius,etc.) and the more expressionistic artists I obsessed over later on (Munoz, Kaz, Panter, etc.) who are more about ink on paper. Whatever I draw like is a result of that mess. And working at the Cartoon Museum has exposed me much more, lately, to the likes of Pont and Searle and Steadman. Basically, everything is in there from the The Beano to Weirdo. but naming a couple? How about Will Elder and Max Andersson? That’ll do.

Coming back to your frequent collaborator David Hine, what do you put the success of your creative partnership down to? Just why are your individual mindscapes in such a beautiful yet terrifying state of creative synchronicity?

Gawd, I don’t know, I love Dave partly because he’s in love with storytelling, with the arts in general, he still buys books and comics and watches films all the time, and not just the genre stuff you might expect from his work, but everything. He’s just lent me Stoner, I just hipped him to The Replacements. I like the way he crafts a story, he does stuff in his scripts I don’t expect, and I can surprise him with my choices, but we both have the same priorities. We make each other laugh..

Gawd, I don’t know, I love Dave partly because he’s in love with storytelling, with the arts in general, he still buys books and comics and watches films all the time, and not just the genre stuff you might expect from his work, but everything. He’s just lent me Stoner, I just hipped him to The Replacements. I like the way he crafts a story, he does stuff in his scripts I don’t expect, and I can surprise him with my choices, but we both have the same priorities. We make each other laugh..

Your major collaboration with David was the adaptation of Victor Hugo’s The Man Who Laughs from SelfMadeHero. Given the sometimes rather rambling nature of the novel with its frequent digressions and asides what were the key challenges in bringing Hugo’s tale to a different medium?

That was mainly Dave’s problem, which I didn’t envy at all. I read the book a couple of times, and it’s full of beautiful and interesting things that have nothing to do with the bloody story. Hugo was very much part of the ‘tell, don’t show’ tradition, and we were working in a ‘show, don’t tell’ medium, so a lot of stuff had to hit the wall, and a lot of other stuff had to be re-arranged to make it into the more cohesive, less digressive romantic tragedy that Dave saw in it, and that he sold to me.

My job was to put everything at the service of that story, to make you care about that kid abandoned in the snow. Frankly, I wanted to make people cry, which is a tall order for someone who draws kind of weird. But I’ve met a couple of people who have. So I’m happy now.

What are you able to disclose at this stage about your contribution to the Broken Frontier anthology?

Not much, other than I’m looking forward to it, I want to work on a larger scale than I have been, and do something expressionistic and inky. But we’ll see what happens when I start it.

The first full-length graphic novel you worked on was Cherubs! with Bryan Talbot. Was that a steep learning curve? And how daunting was it to collaborate with such an industry legend on your first major project?

Pretty bloody daunting, mainly in its length and breadth: most of the stuff I had created up to that point was well under ten pages, usually set in a pub, with everybody dying in pretty short order. Cherubs! was about two hundred pages of work, and the first page asked me to draw Heaven.

Pretty bloody daunting, mainly in its length and breadth: most of the stuff I had created up to that point was well under ten pages, usually set in a pub, with everybody dying in pretty short order. Cherubs! was about two hundred pages of work, and the first page asked me to draw Heaven.

Gawd knows why Bryan had faith in me, but I’m so glad he did, it was like graphic storytelling bootcamp. I had to depict everything in that story, Hell, Limbo, New York, renaissance masterpieces, dancing girls, the apocalypse, and working through Bryan’s layouts made me really think about pacing and eye level and page turns and all the graphic novel stuff that doesn’t necessarily apply on shorter pieces. I’d read and loved his work for a long time, and should have been more nervous, but he’s so approachable and generous that the collaboration was a breeze. I learned a hell of a lot, and it gave me a confidence in my abilities that I didn’t really have before, I’m proud of what we did with that book. Now if only more people would buy it…

You also contributed to Ravi Thornton’s Broken Frontier Award-nominated HOAX Psychosis Blues multi-creator graphic memoir last year based on the poetry of her late brother Rob. How did you become involved with that book?

It’s all a bit fuzzy, and involved drinking and dancing at the Phoenix bar on the night of the Comica Festival launch, I’m not sure what happened, but Ravi got hold of me by email later, mentioned that I’d kissed her eyelids, and talked about the book, I said yes and I’m glad I did. The book’s beautiful. I lost one of my best friends to mental illness and suicide a few years ago, and it was just a horrible, stupid, traumatic thing that left me feeling helpless and guilty.

Working on HOAX was wholly positive, however, after a long haul of solid storytelling set in 1710 on The Man Who Laughs, I got to draw six pages of expressionistic blowout and oneiric oddness (sample image below) and enjoyed it immensely. I only knew about my little bit, and the chapter before, and I was delighted when I saw the finished thing, everybody did such a great job.

You’re currently working on yet another Hine/Stafford collaboration ‘The Bad Bad Place’ (below right) in Soaring Penguin Press’s Meanwhile… anthology. What’s the basic premise of the strip and to what degree – if any – has the discipline of creating for a serial changed the approach to the pacing of the material?

The premise is that a bad old house suddenly appears in a shiny new town, and murky business ensues. It’s our first collaboration set in modern day Britain, it’s not an adaptation, and we’re having dark dark fun times. We’re about half way through now, and people have only seen the first two parts, so I’m curious to see what the reaction is as we’re going along. I think the serial nature has lead to some pretty compressed storytelling, so it’ll be a dense little blast of creepy when we pull it together.

You’ve been the Cartoonist-in-Residence at the Cartoon Museum in London for a number of years now. What does that role entail?

You’ve been the Cartoonist-in-Residence at the Cartoon Museum in London for a number of years now. What does that role entail?

Mainly quaffing wine at launch parties and laughing at Martin Rowson’s jokes, these days. I used to run the family fun days each month, and I still produce little bits of art for the museum when asked. I made a lot of worksheets for kids to scribble on and illustrations for the educational material. What I try to do nowadays is come in a couple of days a week and just work on whatever I’m working on in the young artists gallery, so visitors can have a look and ask me about it. So I’m up there at the moment drawing The Bad Bad Place, if you want to come and poke me with sticks.

This year I’ll also be at a number of conventions with Alison Brown, who manages the shop, spreading the word about the place and what we do. The Cartoon Museum is, on the whole, pretty bloody marvelous, and I want more people to know about it and go there.

The Comics Creators Project, backed by a Heritage Lottery Grant was recently announced and launched at the museum. What does that mean for the future of the Cartoon Museum’s collections?

Yes, rather amazingly we’ve just got a sizeable chunk of change from the Heritage Lottery people to buy original British comic art, so that we can stop it disappearing into a million musty drawers and display it to the public. We’ve already got some lovely bits of Bellamy, and Hampson and the like, and art from Ennis/Pleece’s True Faith, which is pretty bloody cool, but would love it if people got in touch with suggestions about what to buy next.

We’re also starting to set up a creators membership scheme, with benefits and invites and social events and such. I don’t think the Museum has been on the radar, so to speak, of much of the comics community, and we should be. If only so that some of the buggers will donate a page or three….

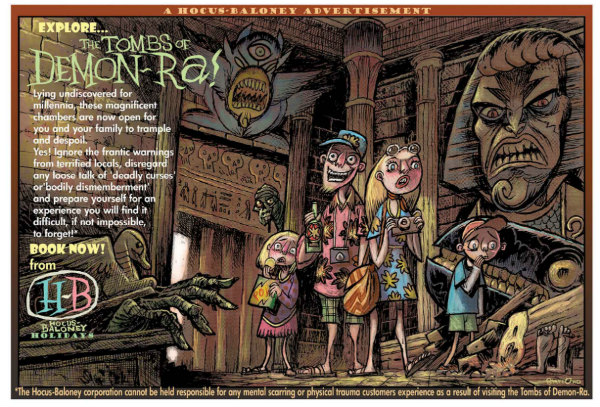

One of Mark’s contributions to the last Moose Kid Comics anthology

Looking forward, what else can we expect to see from Mark Stafford in 2015 and beyond?

Well, obviously more Bad Bad Place is coming up in Meanwhile, and I’ve got another couple of pages in the second Moose Kid anthology I should be getting on with. Apart from that Mr Hine and I have been having long conversations, and I’ve been creating a fair amount of concept stuff for Lip Hook, which is our big fat tale of rural unease that we want to produce as a graphic novel. In my head at the moment it’s a kind of Nigel Kneale/Ben Wheatley/William Burroughs affair of apocalyptic religious mania and church fetes, Lord knows what it’ll be like if and when we get the beast greenlit.

Also I’d like to collaborate with Steven J Harris, on three books I’ve got ideas and outlines for, but that’s early days and I don’t want to jinx them by blathering on too much. I’m sure other odds and sods will arise….

For more on the work of Mark Stafford visit his website here. Find out more about the work of the Cartoon Museum here.

[…] Andy Oliver, Broken Frontier […]