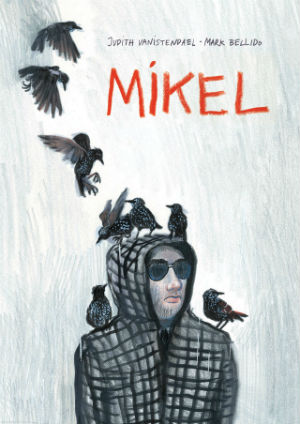

From the outset, Mikel interweaves two stories together: a man’s longing to become a writer, and the story he eventually ends up telling, of a man putting his family and his life on the line – to protect politicians in Basque Country from the armed separatist group ETA. The story is based on the experiences of writer Mark Bellido and is brought to life by the subtle intentionality of Judith Vanistendael’s art, in a work that entertains, intrigues and informs readers of what life was like living in Basque Country during this frenzy of separatist activity. Mikel touches on humankind’s preoccupation with storytelling and the impatience and restlessness this evokes, with main character Mikel uprooting his life in search of a story to tell – no matter the cost.

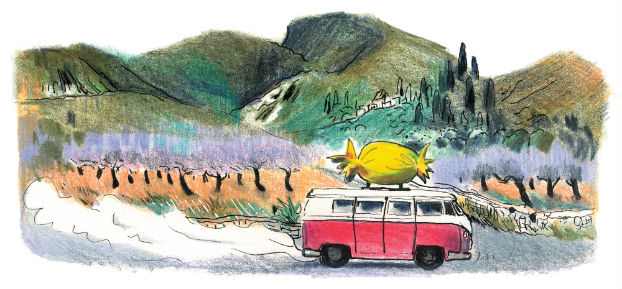

Mikel’s prologue could be a completely different book compared to what is to come, and is where we are introduced to Mikel, his strained relationship with his wife, his adoration for his sons, and his quaint life living in the Spanish countryside, selling sweets. Vanistendael’s colours are warm and gentle for the most part, presenting a stark contrast to the dark, grey tones used later on. Feeling his current life is too quiet and uninspiring to aid his writer’s block, Mikel decides moves his family across the country to the Basque County, becoming a contractual bodyguard for target Javier, or ‘Tango 55’, an elderly man who is on ETA’s radar.

Mikel’s prologue could be a completely different book compared to what is to come, and is where we are introduced to Mikel, his strained relationship with his wife, his adoration for his sons, and his quaint life living in the Spanish countryside, selling sweets. Vanistendael’s colours are warm and gentle for the most part, presenting a stark contrast to the dark, grey tones used later on. Feeling his current life is too quiet and uninspiring to aid his writer’s block, Mikel decides moves his family across the country to the Basque County, becoming a contractual bodyguard for target Javier, or ‘Tango 55’, an elderly man who is on ETA’s radar.

Throughout this tale, Bellido considers the nature of desire itself, and the inherent contradiction in the act of ‘wanting’: when you finally get the thing you have been wanting, you no longer want it and it is in fact the desire itself that actually provides the drive and enjoyment. Mikel forces us to consider the costs of ambitious determination as we see Mikel take things into his own hands by manually forging his life into the one he would want to write about. Following from this, Mikel also provides a commentary on the fact that within our society people choose to do certain things specifically to share that experience with others, often via social media, and how we cultivate versions of ourselves by already looking from the outside, already imagining our experiences in the past-tense, and already recounting them during their unfolding. Mikel epitomises this habit of ours; literally changing his path in life in the hopes of a better story to tell.

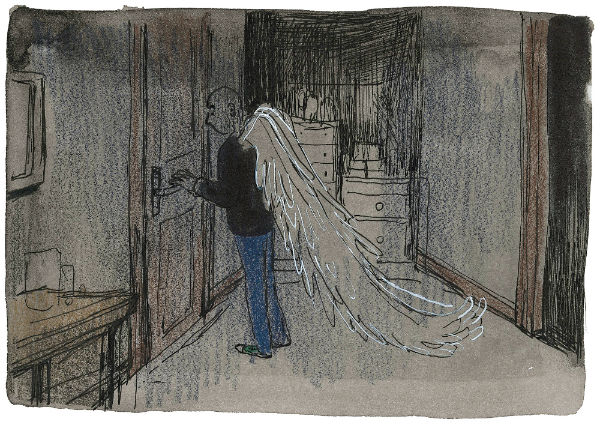

Indeed, Mikel plays the individualist goal of becoming a writer against the pervasive, macrocosmic goal of staying alive. Mikel’s struggle to hold his family together and find the motivation to actually sit down and write seems meek and mild in comparison to his day job, where he must think like the enemy in order to protect a man’s life. At the same time, Vanistendael’s lines become looser and less connected during the more personal, emotive moments: when voices are raised between Mikel and his wife, or his work partner Rosa, and when he is anxious and afraid. In one scene where Mikel returns home after his first day on the job, the colours spill easily through the fragile lines, showing the overwhelming nature of the moment for Mikel and how his sons’ warmth envelops and soothes him. This technique is used again and again to emphasis the emotive nature of scenes, likewise being played in contrast to the rough lines and clear images used while Mikel is on duty, when violence and attack could be imminent.

Despite the serious topics it alludes to, Mikel is full of humour and gentleness, with shorter more surreal scenes thrown in against longer more dramatic moments: to both alleviate the tensions of the story and allow the reader a deeper insight into Mikel’s mental state. Mikel is a gripping read which reminds readers of the complexity and undeniable realness of those who may get bound up in politics, and poses interesting questions about ambition and desire.

Mark Bellido (W), Judith Vanistendael (A) • SelfMadeHero, £24.99

Review by Rebecca Burke