Upon receiving my copy of Nervosa from Street Noise Books, I was surprised that I hadn’t come across the work of cartoonist Hayley Gold before. Gold seems to be a relatively new rising star in the graphic novel industry – a fact that makes Nervosa’s serious subject matter even more of a mean feat. Nervosa, a medical term meaning a disorder of the nerves or mind, is Gold’s first graphic memoir, and is a retelling of her own experience with disordered eating. Throughout the pages, the reader is taken through Gold’s personal experience with anorexia; we’re issuing a trigger warning here for those who struggle with eating disorders themselves, or who would find this a difficult topic to read about.

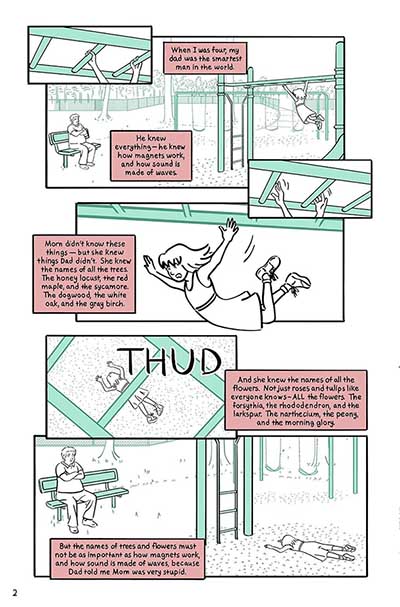

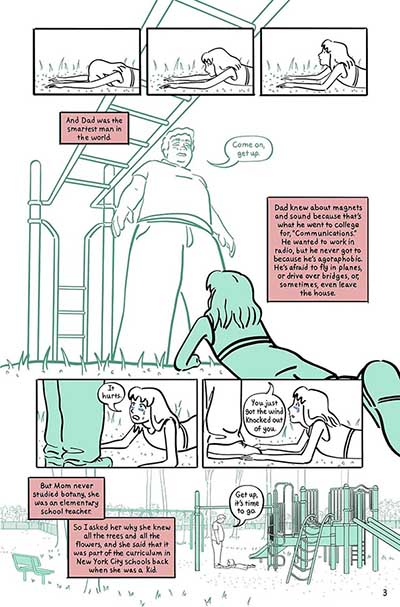

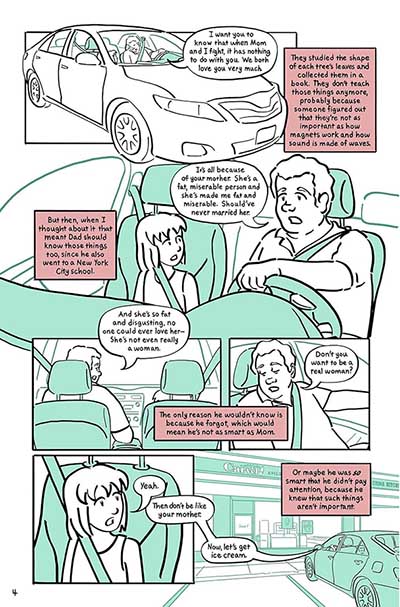

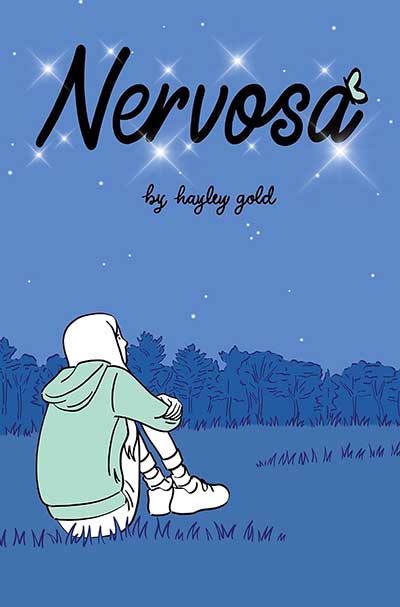

Nervosa is almost childlike in its introduction; the cobalt blue cover showcases the title in calligraphic handwriting, with sparkles surrounding the words and a butterfly perched on the top. This theme continues to the index page, in which each chapter is represented by a brightly coloured butterfly. The oxymoronic nature of a debilitating illness being contrasted with sparkles and butterflies may be representative of the childlike innocence Gold loses throughout Nervosa as she fights against her disorder. As we learn at the beginning of Nervosa, for Gold it began at age four. Her father would often make debilitating comments about her mother’s weight, “she’s so fat and disgusting, no one could ever love her. She’s not even really a woman”, having a profoundly sinister impact on her developing mind.

Coupled with this, Gold is incorrectly diagnosed with a cholesterol problem, so begins to pay attention to the ‘numbers’ on the back of food packets. As a child, she has limited control over what she is given to eat, but as she grows up, her reliance on numbers and obsession with them only grows: “I liked the numbers because they limit choices”. Again, this is visually represented through the recurring butterfly motif, as Gold captures the numbered butterflies with a net, representative of her need to contain and feel in control of them – she is unable to eat the food her mother puts on her plate because it is unmeasured, and she can only see food in numbers. The situation accelerates, as chapter one ends with Gold staying in a children’s hospital after reaching a dangerously low weight.

Gold’s experience of being at the hospital is not at all positive; the doctors seem to treat her as a case, rather than as a human, as she coins them “Dr-You’ll-Never-See-Me-Again”, “Dr So-And-So” and doctors “Gawk” and “Stare”. Medical decisions are not explained to her in the way she needs them to be, with “because I say so” being the default answer to her questions. Her lack of autonomy over any decisions involving her health care is not at all helpful, not even being asked how she feels as the adults around her talk about her illness as if she isn’t present: “the number [the scales] yielded was… the summation of my worth as a human being”. In a complete reversal of intent, this focus on weight, unsurprisingly, only fuels Gold’s obsession with numbers more; due in part to the hospital’s broad categorisation and lack of humane interest in her as anything other than a patient, Gold BECOMES a number, as her entire identity is tied up in what the scales say. Living through this with Gold is terrifying and extremely emotional. Her story only gets bleaker as we read on, as she is passed from hospital to hospital and mistreated.

Midway through Nervosa, Gold splits herself into two characters to represent her trauma; light blue for the Gold that fronts, and that still has a little hope, and a darker blue for the Gold that is her anorexia personified, whispering harmful stereotypes in her ear, and sometimes fronting without her even realising. Gold generally sticks to black and white sketches for most of the graphic novel, so the parts in cobalt blue hues really stand out when used to emphasise a certain character or heightened emotions. Perhaps most unique are the poems accompanying flower sketches at the beginning of each chapter from Emily Dickinson, including ‘A Word is Dead’, aptly mirroring how Gold’s father’s harmful words never withered away, and always stayed with her. Each carefully curated Dickinson poem hints at what will come in the chapter ahead; ‘Much Madness is Divinest Sense’ hints at Gold’s struggles with her doctors treating her as if she is out of her mind, ‘I Felt a Cleaving in my Mind’ about fitting into a new sense of reality, ‘Cocoon Above! Cocoon below!’ about transformation, and so many more.

The strength shown by Gold to be so painstakingly honest about her experience in writing about her disorder is admirable – at many times throughout Nervosa I wanted to cry, to shout, to help Gold through her pain – there are few graphic novels that evoke such a guttural feeling of empathy for another human being, but Nervosa is one of them.

Hayley Gold (W/A) • Street Noise Books, $21.99

Review by Lydia Turner