As recently as the not-actually-that-long-ago pre-internet days, comics were a perilously ephemeral form – especially in the short-run circles of the small press. With no way to keep a comic ‘on tap’, once it was gone, it was gone.

The world moves on. Serendipitous moments end and creative clusters break up: then as now, artists are forced to put comics aside for work that will pay the bills; people move away, start families, maybe decide that they’ve said all they need to say. And then a new generation of hip young pen-slingers steps in to declare Year Zero.

All of that makes it extraordinarily easy for particular stories, comics or even whole bodies of work to slip out of sight beneath the oily swell of time.

All of that makes it extraordinarily easy for particular stories, comics or even whole bodies of work to slip out of sight beneath the oily swell of time.

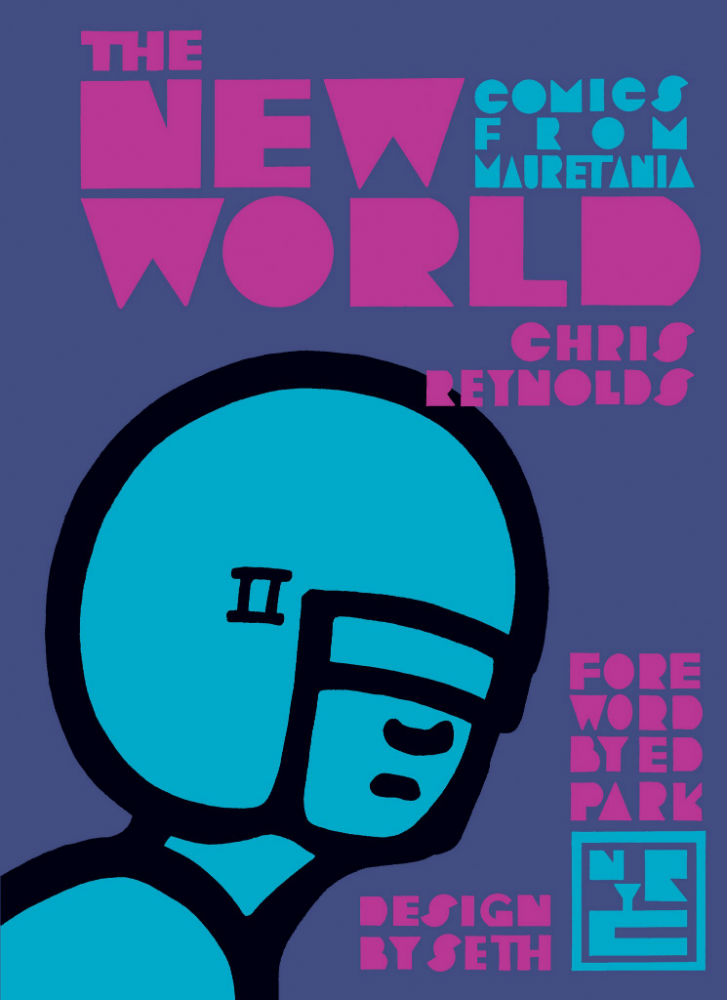

Something along those lines seemed to have claimed the work of Chris Reynolds. During the late 1980s and early 1990s his utterly distinctive Mauretania Comics was a vital presence in the UK small press boom of the time. He was also part of the graphic novel vanguard, with Penguin publishing his book-length Mauretania (collected in this new volume) in 1990.

However, as that era’s collection of talent went their separate ways, Chris Reynolds and Mauretania Comics largely dropped out of sight. And as you luxuriate in the contents of The New World, it’s slightly chilling to think that without the intervention of a high-profile champion (Seth wrote a lengthy appreciation of Reynolds for The Comics Journal back in 2005) we might not be talking about the artist and his work today.

I first became aware of that blossoming small press scene via Paul Gravett and Peter Stanbury’s Escape – a magazine that took some of the richest comics talent, both domestic and international, and put it on newsagents’ shelves in a stylish package that could sit comfortably alongside i-D, The Face and Blitz.

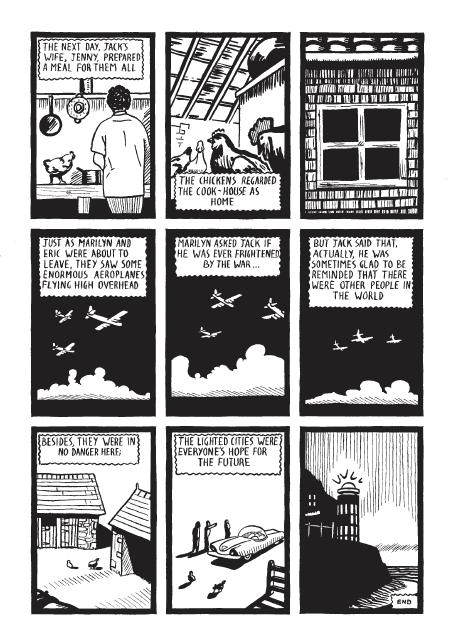

And it was in Escape that I first came across the work of Chris Reynolds, in an instantly arresting two-pager called ‘The Lighted Cities’ (also collected here). It epitomises much of what we’d expect from a Mauretania comic: the bold, high-contrast graphic style, a sense of timelessness, an air of mystery, a heavy emphasis on place and a seemingly artless narration that teases as much as it reveals.

And it was in Escape that I first came across the work of Chris Reynolds, in an instantly arresting two-pager called ‘The Lighted Cities’ (also collected here). It epitomises much of what we’d expect from a Mauretania comic: the bold, high-contrast graphic style, a sense of timelessness, an air of mystery, a heavy emphasis on place and a seemingly artless narration that teases as much as it reveals.

As a film-maker as well as a comics auteur, Reynolds shows a gift for imagery and composition, as well as editing and juxtaposition. There’s a lovely flow to his visual sequences. Particularly in shorter pieces like ‘Our Town’, his images are often like a series of beautifully compact little still lives, capturing within their thick black borders a sense of frozen time.

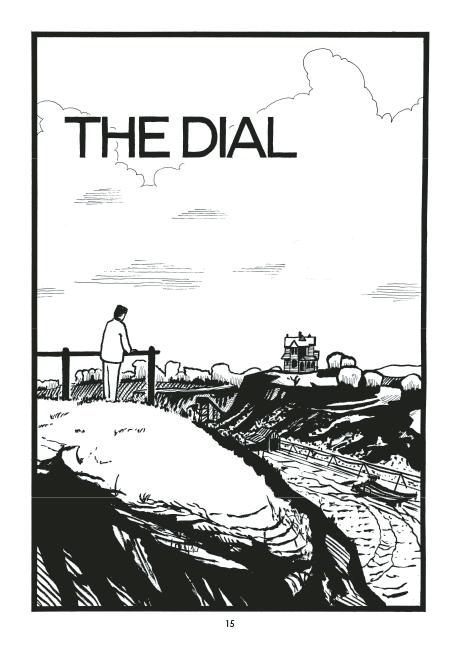

‘The Dial’, The 38-pager that opens this collection,uses its broader canvas to expand on some of these elements, while also unfolding with the asphyxiating logic of an anxiety dream. Returning from war, the protagonist, Reg, finds his home unexpectedly deserted.

As he delves into his family photo albums he notices details and presences that had eluded him before. Cryptic sci-fi elements gradually reveal themselves, and before long outside forces start to close in on him in an increasingly nightmarish way. The story’s conclusion takes it in another unexpected direction, which sheds new light on what we’ve seen and asks another big question about Reg’s return.

As he delves into his family photo albums he notices details and presences that had eluded him before. Cryptic sci-fi elements gradually reveal themselves, and before long outside forces start to close in on him in an increasingly nightmarish way. The story’s conclusion takes it in another unexpected direction, which sheds new light on what we’ve seen and asks another big question about Reg’s return.

Themes recur across the collected stories like musical melodies. While one story explicitly references time travel, revisiting the past is a frequent concern, through either journeys to familiar haunts or the altogether less reliable medium of memory. In a lot of the stories time seems to have stood still; the cafe in ‘Monitor’s Human Reward’ appears to exist in a bubble of stasis, like a relic from the austere post-war world which seems to form the core of Reynolds’ aesthetic. The dreamlike developments of ‘The Dial’ continue here; memories are suddenly activated, but reality fails to match Monitor’s, um, precollections.

As Seth identifies in his afterword, there can be a danger in going back to something you loved years or even decades ago – especially in pop culture. I didn’t get where I am today by shying away from an overcooked and pretentious reference, so here’s Heraclitus: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he’s not the same man.”

As Seth identifies in his afterword, there can be a danger in going back to something you loved years or even decades ago – especially in pop culture. I didn’t get where I am today by shying away from an overcooked and pretentious reference, so here’s Heraclitus: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he’s not the same man.”

However, in that gap, the potential for insight emerges – particularly in Reynolds’ work, with its frequent concern with revisiting the past. In fact, coming back to the work after an absence leaves the reader like the revenant Reg with his photos in ‘The Dial’, picking out details and significance that weren’t apparent at first sight.

A few commentators raised their eyebrows at the prominent credit given to Seth for his design work on this volume, but he has produced a lovely object. We should be grateful to him and the sharp curatorial minds at New York Review Comics for reaching into the past and giving a new generation the opportunity to discover one of comics’ most intriguing bodies of work.

Above all, we should seize with both hands the opportunity to slip back across the border into the compelling world of Chris Reynolds.

Chris Reynolds (W/A) • New York Review Comics, $34.95

Review by Tom Murphy