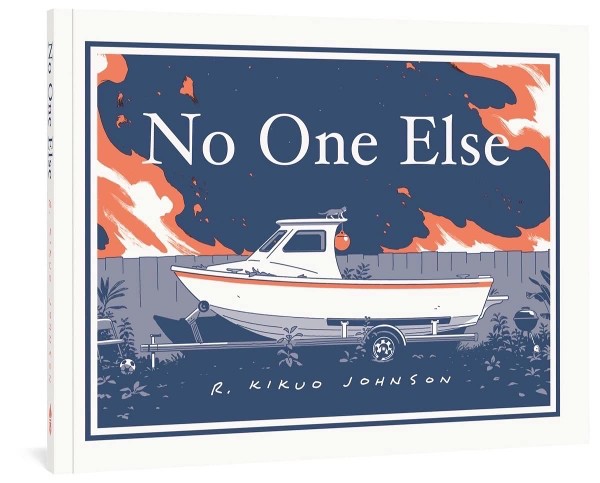

Winner of the Outstanding Graphic Novel in the 2022 Ignatz Awards, No One Else is a sensitively observed family drama from The New Yorker cartoonist R. Kikuo Johnson. It’s one of those slice-of-life offerings that reminds us of human fragility, of the complexities of our closest interpersonal relationships and how, without direct motivation or malice, our life choices can impact on those around us. That Johnson’s 100-plus page short connects with the reader on so many familiar emotional levels without sermonising but, rather, a quiet sense of introspection is a testament to the subtle power of his visual storytelling.

No One Else follows the interlocking stories of three characters: divorced single mother Charlene who for the last seven years has been the sole carer for her father who appears to have been suffering from dementia; her brother Robbie who left the family years ago to attempt to realise his dreams of music stardom; and her young son Brandon whose closest companion is his cat Batman.

After Charlene’s father dies following a fall at home she withdraws into her own world, focussing on nothing but her studies. This leaves Brandon to take on all domestic responsibilities and plunges the household into serious debt. When Robbie returns to celebrate Brandon’s birthday he discovers a home in crisis, an unresponsive sister who has informed no one, including the family, of their recent bereavement, and Brandon’s world in turmoil. As Robbie takes on parental responsibility for his nephew, old truths return to the surface and simmering resentments come to the boil.

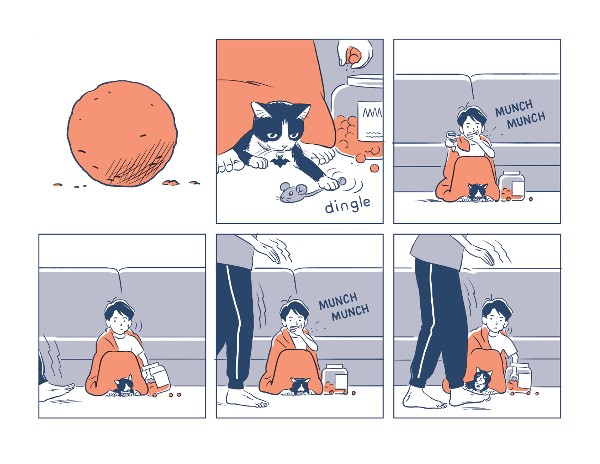

This is indeed a most melancholic graphic novel but it’s in that same pensiveness and understatement that the audience recognises experiences that have a universal quality. Robbie is exasperated at what he considers to be Charlene’s selfishness since their father’s passing. But at the same time he fails to recognise his own self-centredness and the pressures his absence over the years put on her. Charlene, meanwhile, throws herself into an obsession with self-improvement that is about bettering the family position, but in so doing is bringing them to the brink of personal disaster. Meanwhile Brandon has become solely concerned with the missing Batman, a subplot that in its culmination will mirror the wider events of the book with an indeterminate yet strangely resonant symmetry.

On a very surface level No One Else is about a family falling apart after a loss, but as the story progresses we begin to realise that rather than being the catalyst for those strained relationships the bereavement the characters suffer is merely shining a light on long-standing grievances and human flaws. Johnson’s landscape format book with its restricted colour palette adds to the subdued tone of the story with his clean lines and delicate visual characterisation ensuring that we know as much about the characters from their expressive qualities as we do from their dialogue.

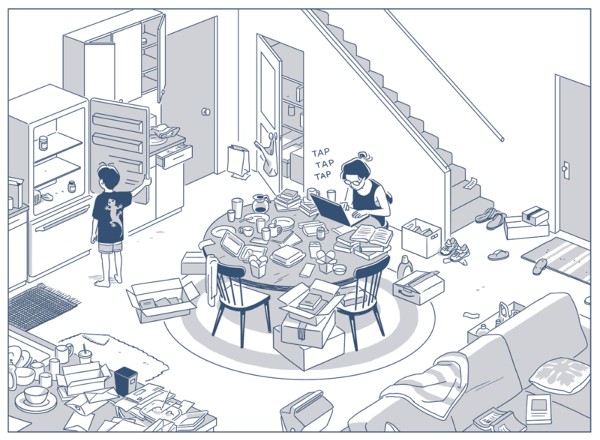

There are also many eloquent examples of comics’ relationship with the passage of time; in particular one full-page spread of Charlene working in a fastidiously clean and tidy living room contrasted with exactly the same scene two pages and some days or weeks later but with a mire of rubbish, unwashed crockery and fast food packaging. An upsetting indication of her rapidly expanding depressive state that needs no further elucidation.

For all the negative commentary that can sometimes surround comics awards and the ranking of art they still serve a valuable purpose in alerting potential readers to projects and creators they may otherwise not have been aware of. Even those of us who consider ourselves well-versed in the form can miss high quality and high profile work like No One Else and I remain indebted to this year’s Ignatz voters for remedying my oversight.

R. Kikuo Johnson (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books, $16.99

Review by Andy Oliver