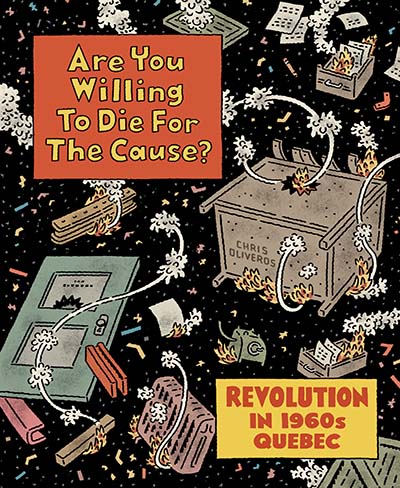

History lessons aren’t always easy to stomach, which may explain why so many of us refuse to learn from them. Recent events only reinforce this, making the work of artists like Chris Oliveros more important than ever. It’s been a long time since the founder of Drawn + Quarterly published something of his own and the good news is, Are You Willing to Die for the Cause?: Revolution in 1960s Quebec is more than worth the wait.

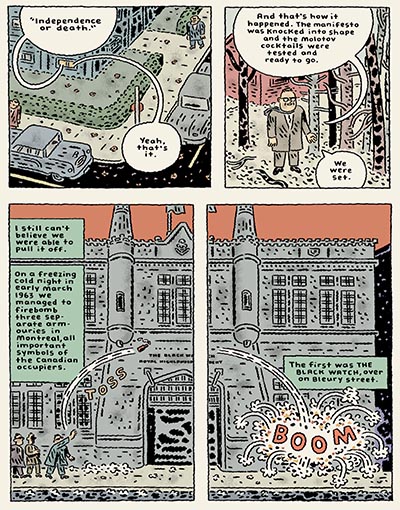

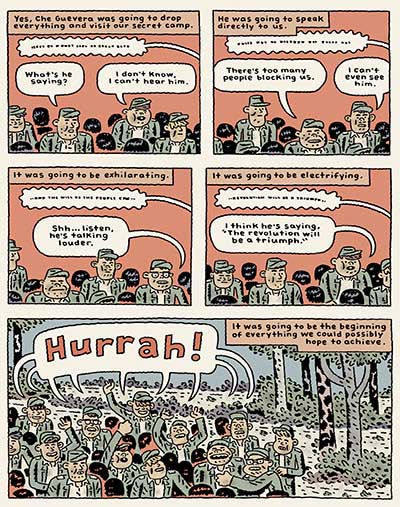

The book shines a light on the Front de libération du Québec, or FLQ, a separatist movement that evolved into a terrorist group. Founded in 1963 and active until the early 1970s, it came into being with the sole purpose of establishing an independent Quebec through any means necessary. What Oliveros does so well is humanise the key players in that struggle. There are fascinating revelations along the way, culled from memoirs, testimonies, and newspaper reports buried for decades.

This isn’t just an artistic achievement; it is also a triumph of journalism because of how Oliveros weaves fact with fiction, beautifully capturing Montreal in the 1960s while offering nuanced explanations of why and how the FLQ was formed by European immigrants. He is reportedly working on a second book that continues the FLQ’s story and tells us how it faded away.

Are You Willing to Die For The Cause? may be set in the 1960s, but its lessons are pertinent to our time of demagogues and weakened democracies. We asked Oliveros about his childhood in Montreal, his research, and what drew him to this period. Here are his responses.

BROKEN FRONTIER: You were born in 1966, around three years after the Front de libération du Québec was officially founded. To what extent were you aware of their presence while growing up in Chomedey?

CHRIS OLIVEROS: I was born at the tail end of the events covered in this book, so I have no direct memories of this period. I first became aware of the FLQ in my grade 10 Canadian History class, when we saw a documentary by the NFB (National Film Board of Canada) on the subject. I remember being riveted by what I learned. Somehow the subject stuck with me for all of these years.

BF: There have been some interesting depictions of the FLQ in popular culture, from cinema (Corbo, Nô) to fiction (Brian Moore’s The Revolution Script). What did you intend to add to this conversation with a graphic history of that period?

OLIVEROS: With the exception of the film Corbo, most of the adaptations of the FLQ have focused on the figures behind the 1970 kidnappings. But when I started researching the FLQ activities of the 1960s, I was surprised to discover that there was very little in-depth material written in English about this period, beyond two books and a recent CBC podcast. So, my goal was to create an accessible and engaging, well-researched graphic novel on the topic.

BF: This is obviously a labour of love, given the years you have spent working on it. Did your perspective of the FLQ change over time in any way?

OLIVEROS: Through researching this book, I came to have a greater understanding of what motivated the FLQ to want to overturn a system that profoundly oppressed the French-speaking majority in Quebec of the era. While I had a general awareness of the inequality during this period, some of the statistics are staggering: when the FLQ first began in 1963, many francophones earned barely half of their English-speaking counterparts. As well, the education system effectively created a one-track stream for francophones, steering them into lower-paid factory jobs.

BF: Sean Rogers once described you as “the youngest son of a Spanish immigrant psychiatrist and a Manitoba transplant.” Did you have conversations with your immediate family about the FLQ, given that their impressions of the time were presumably more vivid and radically at odds with what their peers were saying?

OLIVEROS: No, I can’t remember a single time my family mentioned the FLQ while I was growing up. Although when I talked to my mother while I was working on this book, she had a few memories about hearing about the mailbox bombings when she would have been a 19-year old mother.

BF: You founded D+Q with a belief in ‘the potential for intelligent comics of distinguished quality to succeed with a cultured readership.’ How do you evaluate its successes by that parameter, after stepping down as publisher?

OLIVEROS: It would be difficult for me to overstate how proud I am of the incredible people who have taken over D+Q since I stepped down. The key figures, from Peggy Burns and Tom Devlin to Tracy Hurren and Julia Pohl-Miranda and so many others, have really expanded the scope of what D+Q represents.

BF: The Envelope Manufacturer was set in 1960s Montreal, much the same era as Are You Willing to Die For the Cause?. As an artist, what compels you to always look back?

OLIVEROS: I’m fascinated by the design, style, and general imagery of a fairly narrow period in history: about 1963 to 1972. So much so, that I doubt I’ll ever set a story in any other time frame! Somehow the idea of drawing someone sitting at a computer, or of drawing some hideous SUV monster truck, does not seem very appealing to me.

BF: Trust in the government appears to be at an all-time low across most Western democracies. Did recent developments affect how you approached your book, towards the end?

OLIVEROS: I started working on this book in early 2016, when the world seemed like a very different place. Unfortunately, the sort of events depicted in this book now seem far less remote.

Interview by Lindsay Pereira