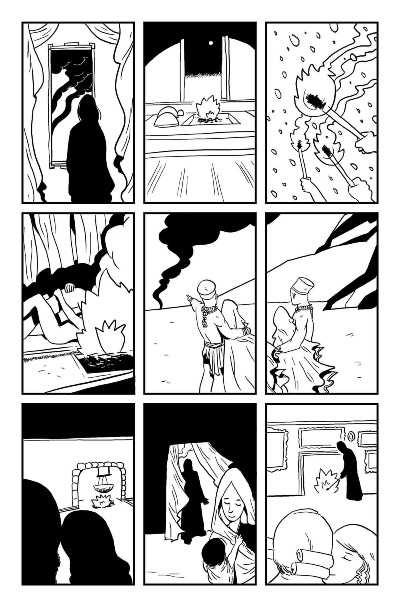

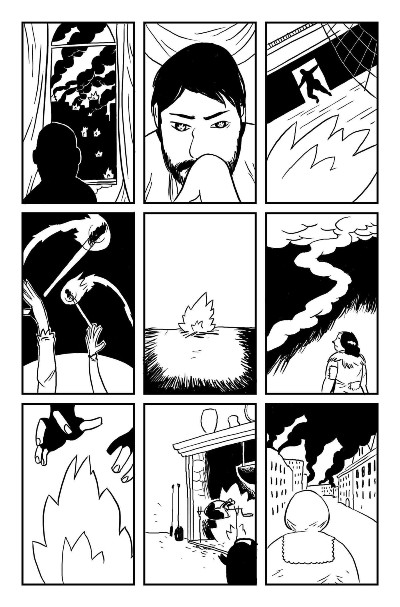

Many things happen in Ray Fawkes’ ambitious, experimental montage comic One Line – roughly 7 generations are presented 18 times over – but the core is conveyed by the silent, panel-per-page prologue. There, a prehistoric family huddle around a campfire, before another man leaps into the cave and murders the patriarch. As he warms his hands, the child looks on in anger. Humanity is connected, but instead of commonality it leads to contention, fighting over resources which sparks resentment and intergenerational feuds. One Line is not wholly bleak, eking out moments of comfort in its long turbulent tapestry. But even if Fawkes aims towards light at the end, it’s hard to ignore that One Line opens with an original sin of killing over fire, and increasingly has its storylines snuffed out into empty black panels.

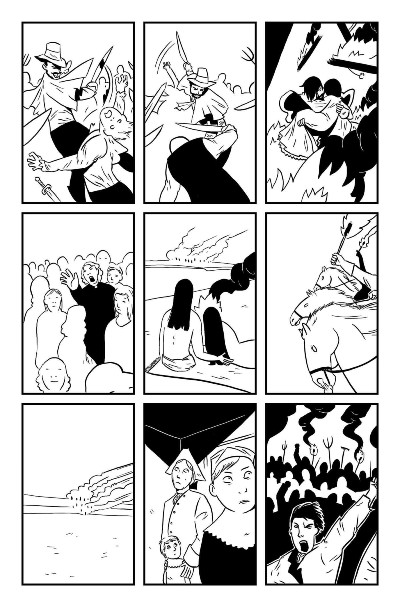

The concept for One Line is this; Fawkes simultaneously represents 18 different storylines. Using a 9-panel grid (doubled across two pages), each “panel” sticks to each individual story and first-person perspective. So, every time you flip the page (or scroll down on digital, ensuring you have “two-page” view) each lineage has progressed within their spatial position. It’s a structure that is unique to the medium of comics, and Fawkes wields it cleverly. For instance, in “Part 1” a pair of brothers share the first two panels given their adjacent stories. “Part 2” focuses on their children, splitting off into different tales, until the “cousins” reunite for a meal, the table crossing the panels in a diptych.

Additionally, each panel is from their protagonists’ perspective, all dialogue conveyed through their thought captions. So, you could feasibly re-read One Line 18 times, only concentrating on each positional panel. But most will read One Line “normally,” letting each step of a single journey be interrupted by 17 other paths. Fawkes carefully choses the staccato statements on each page, making the stories contribute and gestalt into an oddly collective one, albeit fragmented like e. e. cummings poetry. Phrases and events chime or contrast off the ones around them, all of the characters so close together but rarely able to see outside their own boxes.

As a result, One Line reads like a mixture of Cloud Atlas, John Dos Passos’ modernist 42nd Parallel and 2014’s Moon Knight #2. One Line is a “spiritual sequel” to Fawkes’ previous 2011 work One Soul, which I admit I have not read, but appears to use the same structure. But One Line appears even more ambitious, charting history from the 1700s to the present while spanning religions, race, countries and class. It’s tough not to be impressed by the scope and spartan poetry of One Line, even if actually read it can be quite taxing. Fawkes’ neat and simple linework is visually pleasing, but it does make it hard to differentiate the characters sometimes. 18 stories is a lot to keep track of, so One Line may take several attempts to fully comprehend (although some may see this as a benefit). But it’s probably not a good sign that when lineages end early without descendants – resulting in panels being blacked out for the remainder of the comic – it almost comes as a relief.

Yet this density cannot be discounted. Reading through One Line reveals new dynamics and revelations about the panels and their relation to one another. Fawkes uses the unique language of comics to tell a sprawling story of humanity, both our similarities and differences, as we fight and collide off each other for dominance without being able to see the big picture. One Line zooms out, displaying these very human tales all happening at once. It can makes the comic tough to grasp onto and unwieldy, but with enough patience and care such complexity can turn into transcendence in viewing our interwoven stories as single strands (and vice-versa), all at the same time.

Ray Fawkes (W/A) • Oni Press, $24.99

Review by Bruno Savill de Jong