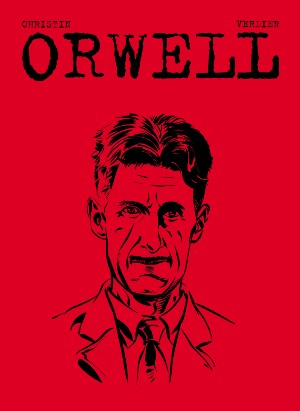

Before his death, Orwell requested that no biography be written about him. That request has been ignored so often that Orwell is only a minor expansion of a collective crime. I wonder whether the man born Eric Blair was embarrassed about fame, or whether he intuited a book about him would unlikely be as good as what he’d written.

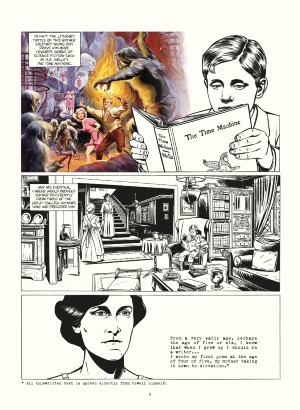

Orwell opens up with four panels spanning four times and locations, suggesting four ways in which Orwell’s origins story could begin, and hinting at the fact that both his family’s and his own story could be drawn out to mimic narratives of English literature, with which the writer himself was no doubt well acquainted with. It’s an interesting proposition. Given that so much of his work was based on his own life (his early fiction even being contrived memoir), and that George Orwell was a pseudonym conjured up by mixing his own and his nation’s mythology, there’s ample potential to do a story inspired by Orwell which investigates the notion that life imittates art, and vice versa, how historical circumstances make a person and their work, and how the production of literature shapes the reality it says it reflects.

Orwell opens up with four panels spanning four times and locations, suggesting four ways in which Orwell’s origins story could begin, and hinting at the fact that both his family’s and his own story could be drawn out to mimic narratives of English literature, with which the writer himself was no doubt well acquainted with. It’s an interesting proposition. Given that so much of his work was based on his own life (his early fiction even being contrived memoir), and that George Orwell was a pseudonym conjured up by mixing his own and his nation’s mythology, there’s ample potential to do a story inspired by Orwell which investigates the notion that life imittates art, and vice versa, how historical circumstances make a person and their work, and how the production of literature shapes the reality it says it reflects.

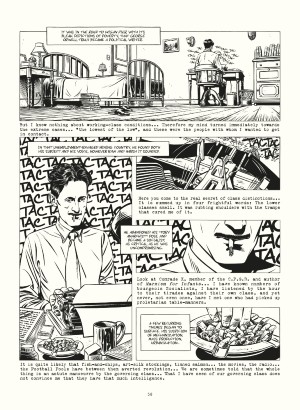

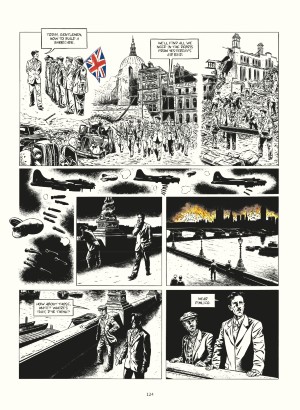

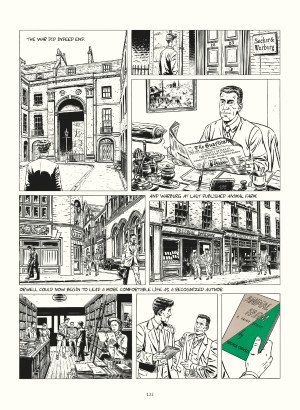

Unfortunately, Orwell doesn’t make much of its own suggestion. We’re quickly taken to Orwell’s upper middle class childhood in the home counties, and from there on in the narrative is strictly linear and remarkably uninterested in literary flourishes. Quotes from Orwell’s work are provided in typewriter font, while writer Pierre Christin’s imagination supplies the dialogue. There are also captions which speak in the third person. That there’s three different voices in the book isn’t as confusing as it sounds, but it does alert the reader to the fact that the authors were very concerned with fitting in as much as possible.

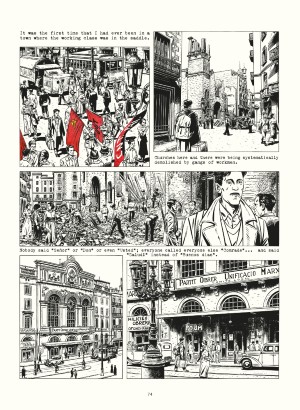

On the topic of fitting stuff in, Sébastien Verdier’s art is bafflingly detailed. His precise inks have all the precision and cleanness of an architect’s design. While this makes London seem more airy than it is (I’m likely always going to see Eddie Campbell’s rendition of the city in From Hell as the ultimate depiction of British Victoriana), it works well for the picturesque moments in the British countryside, and the more ornate and stylised streets of Paris and Barcelona.

While the opening pages (during which Orwell is a child) feel a little static, the later scenes project a greater sense of movement. Heavy hitters in the European comics scene such as Blutch contribute interludes: illustrations for long passages taken directly from Orwell’s books. There’s an efficiency in both the art and the writing in this book. It’s ample for someone who has no idea about Orwell or his legacy, but for those of us who have spent time with his work, there’s something lacking here, despite the amount of stuff.

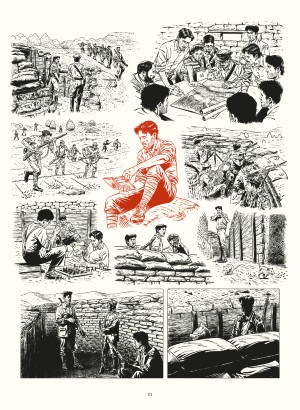

The issue with going from the start to the end of Orwell’s life in the way this book does is that the authors portray a timeline rather than develop themes or inquire into the sort of mind that could embrace the contradictions that Orwell’s did. There’s plenty of scope here, but not enough detail. Additionally, Orwell is too interested in protecting Orwell from criticism, rather than embracing such criticisms in order to make an exciting story (Bennett Miller’s 2005 movie Capote is a good example of a biographical work that respects but doesn’t fawn over its subject).

The lack of critique of Orwell and his work is suspicious. Not least because there’s a lot of controversy to choose from. There’s the issue of Orwell’s homophobia, his distrust of his era’s feminism, and the fact he worked as a spy for the British state during WWII. Homage to Catalonia is a fantastic book, but as Spanish Civil War scholar Paul Preston has made clear, Orwell’s partisan account was based on a very limited understanding of events. I don’t raise these points to deter people from liking his work – I’ll keep reading my copy of The Lion and the Unicorn until it’s dust – but if we don’t get the bits of a person we don’t like, we don’t really get a person at all.

If Orwell wanted to be taken seriously as a historical text, these elements would have been included. Instead we get a book that tries to persuade the reader that the most important thing about history is to read events in chronological order, and in the author’s own words, not whether there’s any disputes about what was or wasn’t included in the narrative during his own lifetime.

In his 1946 essay Why I Write, Orwell stated that: “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.” Such little that has been done with or about Orwell since his death has continued this mission (including, it has to be said, the Foundation that bears his name). Does the reader feel a burning desire to stamp out injustice, possibly with the strength of the working class, after reading Orwell? The answer, I think, is no. Despite its arguably patronising depiction of the working class, not many people could read Road to Wigan Pier and not be moved to think very firmly that the conditions of the working poor are deeply unjust.

In the decades following his death, Orwell’s name has often been used (as it is in the epilogue of this book) in discussions about fake news and political mud-slinging. Too little is it taken as an opportunity to reinvoke his dislike of the establishment, his awareness that colonialism was a sadistic project, and concern for the needs of the many. Perhaps future fans of Orwell should follow his dying wishes, and consign the man himself to history, only taking directly from his work that which is useful for us in the present.

Pierre Christin (W), Sébastien Verdier with Juanjo Guarnido, Enki Bilal, Manu Larcenet, Blutch & André Juillard (A), Edward Gauvin (T) • SelfMadeHero, £14.99

Review by Nicholas Burman