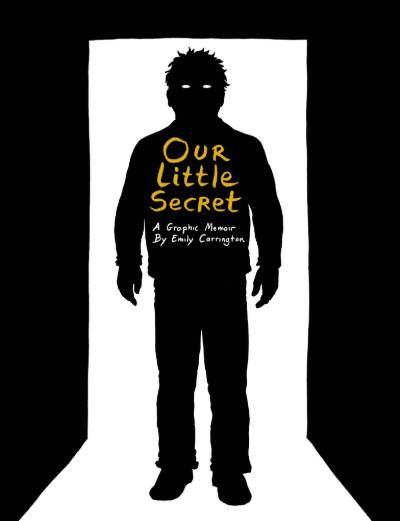

It is impossible to read Emily Carrington’s graphic memoir, Our Little Secret, dispassionately. The pages are weighed down by her documentation of a traumatic personal history, but so many panels also sing with the undeniable effort of her trying to make sense of her own story.

On the surface, this is a book about sexual abuse and its aftermath. It is so much more though, as one slowly starts to recognize it as an act of catharsis.

We asked Carrington about using art to cope with grief, what she hopes readers take away from her work, and whether the comics form is particularly suited to explorations of difficult subjects. Here are her responses.

(Content warning: discussions of sexual assault)

BROKEN FRONTIER: Reading your poem ‘Stone‘, one is struck by the economy of language. You specifically mention using “fewer carefully selected words” and we were wondering how and why you eventually decided to try another medium of expression?

BROKEN FRONTIER: Reading your poem ‘Stone‘, one is struck by the economy of language. You specifically mention using “fewer carefully selected words” and we were wondering how and why you eventually decided to try another medium of expression?

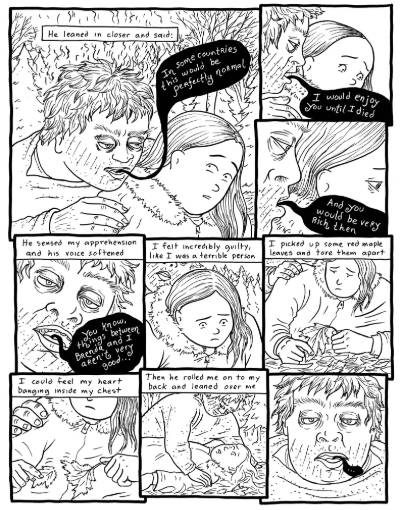

EMILY CARRINGTON: My poem ‘Stone’ was also about sexual abuse and how the aftermath felt like a heavy stone I had to carry with me while my abuser was left completely unscathed. Every time I tried a new form of written self-expression, the sexual abuse was the first thing that came up to the surface. So, after my renewed interest in comics in my mid-forties, I quickly realized that comics were a form of self-expression which, having both images and words, offered a more complete experience for the reader. I treated the creation of the book as an attempt to retrieve memories and re-create what actually happened, as if I had gone back in time with a video camera and documented it all. I wanted the reader to be a witness to the crime that almost never has any witnesses at all. Comics also allowed me to express emotions without words. Facial expressions, arm gestures, textures and composition of the panels all became meaningful. Now I feel no part of the story and memories have been left untold.

BF: You have spoken about a connection between the conscious and subconscious in mythology, and how images are used as visual metaphors. Are you concerned about readers missing some of these cues?

CARRINGTON: Every reader will interpret the story in a different way, depending on a host of factors, including their own experiences, beliefs, and the culture they grew up in. Different cultures may have different meanings for the imagery in the book. My approach was simply to draw these images as they came to me, then try to figure out their significance later. My main goal is to leave the reader with a better understanding of the stages of grooming of child sexual abuse, how disadvantaged children are more at risk, and how the child becomes changed afterward and can suffer from the aftermath for years or even decades, and I think that will be apparent to most readers even if they miss some of the cues. The images can be seen just as images to add visual interest or can be explored to any desired depth. The mixed meanings of the bear as being a protector, a spirit guide or a source of danger are examples. It can be as simple or complex as the reader desires.

BF: Early reviews have drawn favourable comparisons between your work and that of veterans like Joe Sacco. Were you influenced by other memoirs, journalists, or writers working in other media in any way?

CARRINGTON: I am of course very honored to have had such favorable reviews, especially as I had given up on writing comics for so many years. I was greatly influenced by other writers, both inside and outside the comics genre. I would have to say the one book that gave me the courage to tell my whole story more than any others was Greg Gilhooley’s book I am Nobody. When I read it, I thought at so many points – Oh my God, that’s exactly how I felt, or that’s exactly what happened to me. I saw he published his book, and he wasn’t destroyed by telling his story. That’s the fear I think many victims have—that is if you tell your story your abuser will destroy you. That’s the power the abuser wields over their victims. But it is all an illusion. Once you tell your whole story the abuser becomes small, and you see them as the sad twisted creatures that they really are.

BF: It’s interesting how sexual assault is such a major theme even in graphic novels that seemingly have no obvious connection with the issue. Alan Moore’s Watchmen comes to mind, for instance, or Charles Burns’s Black Hole. Do you believe the comic form makes it easier for artists to explore difficult themes?

CARRINGTON: I think each creator has their own way of exploring difficult themes—the artist uses imagery, the musician combines music and words, the writer uses words, and video combines words and images that move. Television is now breaking all of our hearts as we watch people die as a result of the senselessness of war. Tracy Chapman was so believable when she sang about poverty and suffering, and indigenous musicians are teaching us about the injustices they experienced. I feel comics are unique though as our brains seem to be wired to interpret even simple drawings in a complex way. For example, look at the rise of the use of emojis in our messaging. We use it because these simple little images can make us feel or understand something that would take a large amount of writing to try to express. Comics I think allow us to express more in both quantity and depth of experience in a smaller space.

BF: You point out, quite rightly, how child abuse tears apart the lives of victims. Is artistic expression an effective coping mechanism in the long term?

CARRINGTON: After experiencing just about every emotion possible while coming to terms with the abuse, I believe that the “coping mechanisms” people use are for the most part damaging. Drinking, substance abuse, self-harming behaviours—those are examples of coping mechanisms to try to distract from the constant pain that is hidden away, pain who’s source we don’t understand. We are fighting an enemy we can’t see. I think the only true way out of it is to understand the link between the abuse and the damage to your life, and get whatever help you need to come to terms with it and become whole again. I think art, or any other kind of creative outlet, can definitely be a part of that healing process.

BF: The statistics you present in some panels, citing the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics and Statistics Canada, are staggering. What surprised you most about how Canada deals, or fails to deal, with this crisis?

CARRINGTON: The biggest disillusionment for me was discovering the legal system is just—as Greg Gilhooley once said—a system of legal outcomes. It doesn’t necessarily deliver justice. I feel a bit embarrassed now that I was actually expecting justice from this terribly crude and outdated system. My understanding of the statistics that Canada collects on child sexual abuse is that they only cover children 14 and under (it is a part of what they call “child maltreatment before age 15”) and I think doesn’t include children on reservations. What happened to me would not have been counted in those statistics, as I was 15. So, I’m not surprised Canada isn’t helping us, if they can’t even be bothered to count us.

BF: Are there any new artists you have come across that you would recommend to readers of your book?

CARRINGTON: As someone who has only been studying comics for about 4 years, I am still in the midst of the enjoyable process of discovering all kinds of older and newer artists. There are so many good ones! One comic though that comes to mind in relation to my story is Josh Bayer’s book Theth. In it there is so much rawness, chaos, anguish, injustice, and in some places rage, depicted in a way that I haven’t yet seen anywhere else, and I am unable to draw myself. I suppose if there is one emotion I haven’t expressed in my comic it is that raw emotion and rage that Josh illustrates so brilliantly. I think it’s still in me somewhere, hopefully not to come out in some inappropriate place like a lineup in a grocery store…

For more information on Emily Carrington’s Our Little Secret visit the Drawn & Quarterly site here.