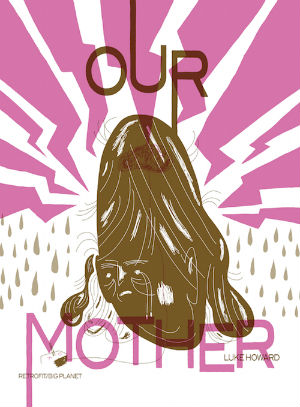

Our Mother by Luke Howard is a masterpiece on all levels. The cartooning is varied and expressive, with a tight sense of design. The intricate way in which multiple narratives, fact and fiction, metaphor and truth are interwoven with the deftest of touches is staggering. The emotional impact of the work is both precise and devastating. Howard performs the work of a graphic novel in this brilliantly paced forty-page comic.

The narrative structure of Our Mother is that of a disjointed palindrome comprised of several parallel narratives, some which loop back on themselves or intersect with their counterparts, and others that serve as commentary on the rest. This creates a piece that is less about the specifics of the story being told and more about the thematic connections between the vignettes. Be it film noir, slice-of-life, fantastic adventure story, science fiction, or laboratory drama; all of the threads in Our Mother deal with the role of motherhood. Yet underlying that connection is that all of the mothers featured are in some way failing in their duties as caretaker, with the pseudo-exception of the storyline in which the daughter takes on the role of caretaker for the stranger she believes has replaced her mother.

The narrative structure of Our Mother is that of a disjointed palindrome comprised of several parallel narratives, some which loop back on themselves or intersect with their counterparts, and others that serve as commentary on the rest. This creates a piece that is less about the specifics of the story being told and more about the thematic connections between the vignettes. Be it film noir, slice-of-life, fantastic adventure story, science fiction, or laboratory drama; all of the threads in Our Mother deal with the role of motherhood. Yet underlying that connection is that all of the mothers featured are in some way failing in their duties as caretaker, with the pseudo-exception of the storyline in which the daughter takes on the role of caretaker for the stranger she believes has replaced her mother.

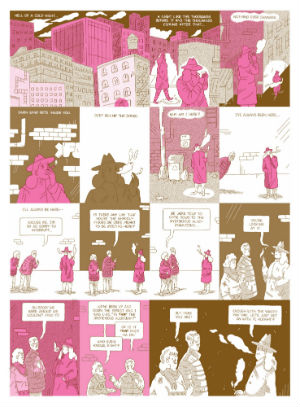

We begin with an unnamed smoking female detective being commissioned by an unnamed mother and father to give their daughter a disorder as part of family tradition. In the first of many grim jokes they suggest “it’d be fun if she just has trouble living most days.” The narrative then cuts to scene of a father callously explaining to his daughter why he is leaving her cripplingly depressed mother. In a strong piece of visual metaphor the panels intercut between the father delivering his speech while moving farther and farther in distance from the family as, simultaneously, the depressed mother’s limbs snake around the daughter and ensnare her. The storyline then continues with what seems to be the same mother and daughter, but rendered in a more upbeat cartoony style. Here the daughter believes the mother to be a stranger who has replaced her original mother, and she begins their quest to return the mute stranger to her home.

Despite the shifts the story has remained relatively grounded until this point. But then we then cut to a post-apocalyptic 2212 where gigantic robot “mothers” harbor the remains of humanity. We zoom in on the pilot of a stranded mother robot desperately trying to get the craft up and running again, however she is trapped inside the cockpit with the useless Kevin whose very presence “turns everything to garbage.” This fantastical turn continues as we return to the stranger mother and cartoon daughter as they float on an eerie lake passing by mysterious doppelgangers then interact with a lake-borne phantasm of the depressed mother who gives her mute counterpart a present. This causes the cartoon daughter to recall her favorite Christmas present, a pair of rollerblades while, unbeknownst to her, menacing forces are creeping in from the sides of the panel.

In the final narrative thread we follow a resigned scientist who resembles the mother as she tests mood-altering drugs on a naïve gorilla. Apologizing to her test subject for what is to come she speaks of how this work will help “a lot of people that are in pain…” This thematically frames the montage for, just as the scientist is failing to protect the gorilla, so too is the pilot failing to protect her passengers, as is the depressed mother her daughter, as is the stranger mother by forcing her daughter to swap roles with her.

At the center point of the palindrome the mute mother and daughter escape from the torture chamber of Count Moldy with the aid of their monkey friend Mr. Jimbles by donning the mustaches we saw earlier on the doppelgangers. They then float back down the river passing their earlier selves who are on their way to repeat the same endless cycle. We return to the gorilla going through massive mood swings as different medications are tested on her. The gorilla’s pain and sadness, standing in for the emotions of the depression sufferer, is so palpable here due to the pathetic and grotesque way Howard renders the gorilla’s performance.

Looping back to the “Mother” robot we see the pilot has killed Kevin only for him to be replaced by a duplicate Kevin, despite the original Kevin’s body laying on the floor in the background. This presages another endless cycle in which the pilot will brutally kill multiple incarnations of Kevin yet never be free of his interference. The mute mother and cartoon daughter end their journey passing through a time portal only to end up at the home of the depressed mother and her daughter. Shifting the opposite direction this time, the story becomes more grounded as we follow the depressed mother and her daughter in the day-to-day grind of the mother’s illness and the daughter’s inability to grasp the stranger her mother has become. Dwelling on the mother’s panic attacks, lack of energy, and inability to eat we recognize all the symptoms that were foreshadowed by the gorilla.

At this point the cycles have all started collapsing in on each other. This is further exemplified by the fourth wall-breaking sequence of photo cut-outs of Howard as a child and his mother discussing how the comic has been about having a parent with anxiety disorder. Connecting the fiction to his own experience we realize that the parents who request the traditional disorder on their daughter in the first scene echoes how multiple generations of Howard’s family have suffered from anxiety disorder. Howard and his mother’s discussion also reveals that anxiety disorder, much like the un-killable pestilence of Kevin in the cockpit, never goes away no matter how much you try to destroy it.

Lastly we collapse things even further as the mute mother betrays the cartoon daughter sending her through another time portal to become the rollerblades the depressed daughter gets for Christmas before her parents split up. The narrative reaches an abrupt conclusion where Howard contemplates his own depression and his slow acceptance of medication and support for his condition over the visual of the farting hotdog he told his mother he would end the comic with.

It is Howard’s confident cartooning that allows him to effortlessly handles all of these tonal and storytelling shifts. On a surface level Our Mother stands out with its gray lines and neon pink spot color riso-ed on off-white paper. Each section’s aesthetic also matches its emotional tenor well. The linework is squiggly and trembling when focused on the depressed mother; crisp and simple when we switch to the cartoon daughter; angular and thin inside the pilot’s futuristic cockpit; and simplified in a Porcellino-esque manner when the daughter narrates her mother’s decline. And while Howard’s characters can at times be lacking in flourish, his panels sparse, or his background simply rendered, they are never sloppy or haphazard.

It is Howard’s confident cartooning that allows him to effortlessly handles all of these tonal and storytelling shifts. On a surface level Our Mother stands out with its gray lines and neon pink spot color riso-ed on off-white paper. Each section’s aesthetic also matches its emotional tenor well. The linework is squiggly and trembling when focused on the depressed mother; crisp and simple when we switch to the cartoon daughter; angular and thin inside the pilot’s futuristic cockpit; and simplified in a Porcellino-esque manner when the daughter narrates her mother’s decline. And while Howard’s characters can at times be lacking in flourish, his panels sparse, or his background simply rendered, they are never sloppy or haphazard.

His strongest asset here is his ability to render the character’s performance. While Howard frequently moves his camera throughout the scene, the focus is almost always on the characters and their emotions. He perfectly captures the frustration and confusion of the depressed daughter, the plucky optimism of the cartoon daughter, the exasperation of both the mother robot and its pilot, and the manic-depressive swings of the drugged gorilla. No one panel anchors the piece, but all briskly move the story along, and all masterfully serve to visually inform the read of Howard’s dialogue.

In Our Mother Howard sets out to conquer a monumental task. Combining multiple narratives in multiple genres while simultaneously making a very pointed statement about anxiety disorders. He is successful on all fronts in this regard. His greatest success here is how well he gets to the heart of the experience of anxiety. It is such a strange and complex thing that no single way of describing it will do. Each of the storylines contributes to encompassing the large nebulous whole of anxiety in a way that recounting the experience could not.

The anxiety sufferer recognizes themselves in Howard’s characters, but so to does the friend or child of the person with anxiety disorder. Allowing for each to develop empathy for the difficult experience the other is going through. Our Mother offers no platitudes but the honest truth that even if depression can never be overcome, it can be dealt with on a day-to-day basis. The first step in that process is having the very real sort of conversations and introspection Howard has within this work.

Luke Howard (W/A) • Retrofit Comics, $9.00

Review by Robin Enrico