If we let it, time will bury everything under dust.

For nearly 200 years, that’s what threatened to happen to the terrible events of August 16th 1819, when a peaceful protest for political reform in Manchester was brutally suppressed by troops, leading to at least 19 deaths. Sardonically dubbed ‘Peterloo’ by a local newspaper, the massacre on St Peter’s Field was a cataclysmic episode in our social history, but it was largely allowed to fade out of the public consciousness – even in Manchester, where only the most euphemistic of blue plaques marked the event.

However, the approach of the event’s 200th anniversary led to renewed interest, including a film by Mike Leigh, a campaign for a fitting memorial and an exhibition at the People’s History Museum in Manchester (which you may well have seen if you visited that splendid venue for Northwest Zinefest last year).

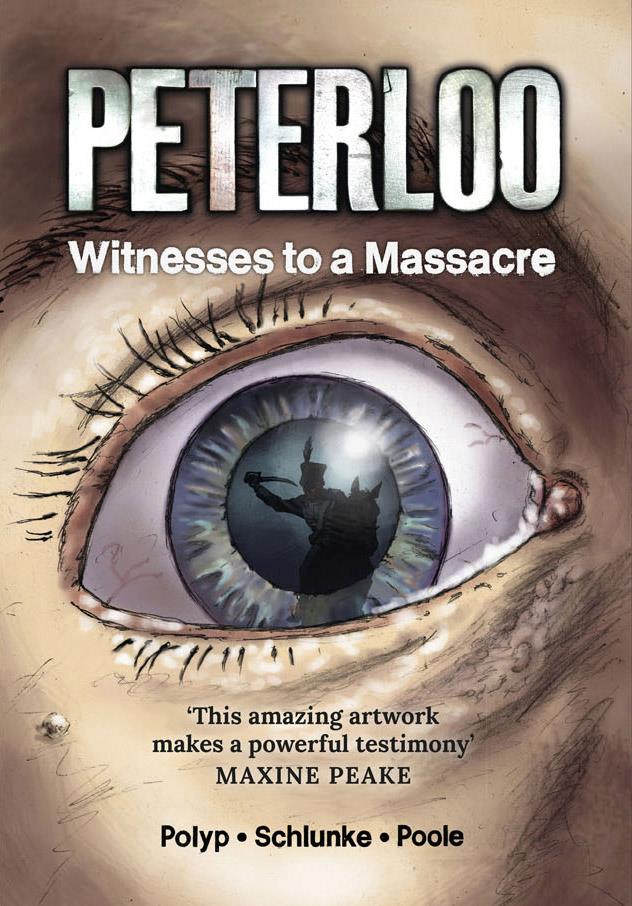

Peterloo: Witnesses to a Massacre is a three-way collaboration between Robert Poole, Professor of History at the University of Central Lancashire and consultant historian to the Peterloo 2019 anniversary programme; Eva Schlunke, an artist, writer and activist who led mass-participation commemorative events in 2015-16; and Polyp (Paul Fitzgerald), a political cartoonist whose books include Speechless (a wordless world history) and The Co-operative Revolution.

Peterloo: Witnesses to a Massacre is a three-way collaboration between Robert Poole, Professor of History at the University of Central Lancashire and consultant historian to the Peterloo 2019 anniversary programme; Eva Schlunke, an artist, writer and activist who led mass-participation commemorative events in 2015-16; and Polyp (Paul Fitzgerald), a political cartoonist whose books include Speechless (a wordless world history) and The Co-operative Revolution.

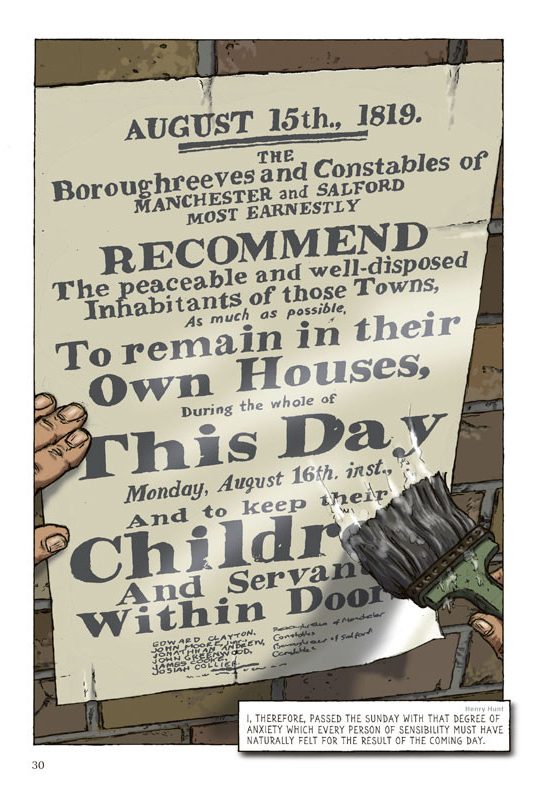

Apart from a few introductory paragraphs and a couple of balloons of purely functional speculative dialogue, the book is a verbatim history: it uses only direct testimony from the time, including letters, official communications, memoirs, newspaper reports and courtroom evidence.

The book unfolds on three levels. The graphic work, which forms the bulk of it, documents the lead-up to August 16th, the terrible events of the day as they unfolded, and the immediate aftermath. Wider context can then be found in the extensive notes at the back, while the list of sources indicates the foundation of scholarship and research on which the book is built (mainly via Poole’s prose history, Peterloo: The English Uprising).

The book sets the stage by depicting vividly the flammable social and political context of 1819. With the recent bloody turmoil of the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror still spooking the authorities, a surging movement was campaigning for parliamentary reform (with a combined population of 150,000, Manchester and Salford still had no representation) and the repeal of the Corn Laws, which protected the interests of landowners by raising prices.

The book sets the stage by depicting vividly the flammable social and political context of 1819. With the recent bloody turmoil of the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror still spooking the authorities, a surging movement was campaigning for parliamentary reform (with a combined population of 150,000, Manchester and Salford still had no representation) and the repeal of the Corn Laws, which protected the interests of landowners by raising prices.

When Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, the white-hatted rock-star performer of his day, was invited to address a rally in the city centre, the national and local authorities prepared to make a bloody and decisive show of strength. And despite the exhilaration of the event, a sense of foreboding ran among the activists.

As a crowd estimated at 60,000 gathered on the day, the magistrates gathered in a nearby house judged that the special constables drafted for the purpose wouldn’t be sufficient to execute the warrant of arrest against the organisers. When they called in the Manchester and Salford Yeoman Cavalry – a heavily armed private militia – the bloody die was cast.

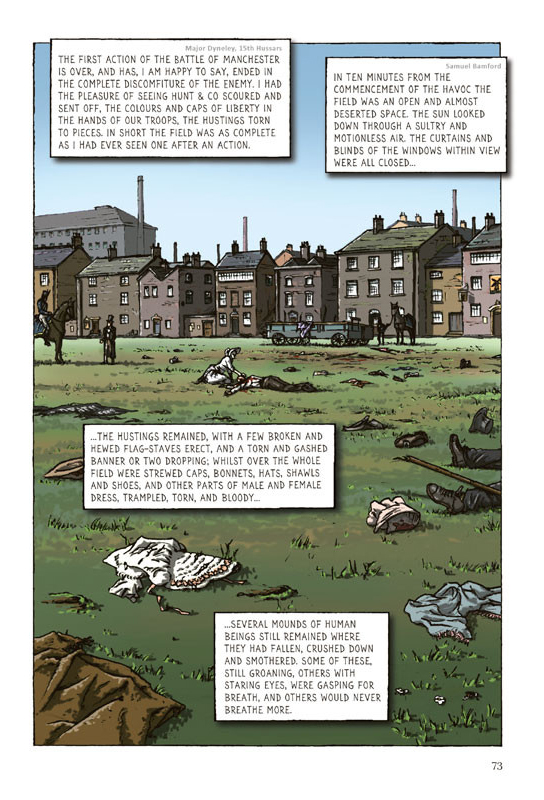

With the drunken and amped-up Yeoman Cavalry galloping towards the field, the day claimed its first victim: two-year-old William Fildes, knocked from his mother’s arms by a horse. On reaching the field they started to slash their way through the crowd with their newly sharpened sabres, and the arrival of the 15th Hussars and other military units brought a fresh wave of panic and carnage. Within 10 minutes the field had been cleared – apart from the piles of dead, dying and wounded.

With the drunken and amped-up Yeoman Cavalry galloping towards the field, the day claimed its first victim: two-year-old William Fildes, knocked from his mother’s arms by a horse. On reaching the field they started to slash their way through the crowd with their newly sharpened sabres, and the arrival of the 15th Hussars and other military units brought a fresh wave of panic and carnage. Within 10 minutes the field had been cleared – apart from the piles of dead, dying and wounded.

In the tense aftermath of the massacre, there was further unrest, bloodshed and suppression. The organisers were imprisoned, and repressive legislation was enacted to prevent future protests. The inquest for one of the victims, John Lees, was blatantly manipulated to prevent a full account of the massacre being made public, and no-one in authority was ever held to account.

Delivered through Polyp’s clear and characterful illustration, there are no fireworks to the storytelling: the link to the contemporary sources keeps it rooted on the right side of artifice or sentimentality. Indeed, the documentary approach emphasises the horror of some of the episodes and facts revealed. Meanwhile, the contrast between the popular and official accounts of the day highlight the self-serving mendacity of the authorities and vested interests; “fake news” isn’t something that just sprang into existence with the arrival of social media.

In his foreword to Jacqueline Riding’s recent book on the massacre, Mike Leigh urged readers of the book and viewers of his film to “Please enjoy them, but do be sure to be both moved and horrified by them.” That request can also be extended to this well constructed and strongly executed piece of work, which shows the part that comics can play in the dissemination of social history.

Robert Poole, Eva Schlunke (W), Polyp (A) • New Internationalist, £11.99

Review by Tom Murphy