Everyone appears to have accepted cinematic adaptations of comic books as totally natural, but the theatre is another matter. There are the odd examples of blockbuster stage translations of comics — a musical version of Alison Bechdel’s autobiographical Fun Home transfers to London’s Young Vic this summer after a Tony award-winning run off-Broadway, and Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark was a stuntman-crippling shambles yet it set records for week one ticket sales — but otherwise you don’t see Marvel, Image or DC dominating TKTS booths the same way that they do the multiplexes and bookshelves.

Which isn’t to say page-to-stage adaptations are completely unheard of. They just tend to fly a little more beneath the radar, as was the case when the smaller Southwark Playhouse’s brought the feudal furry Japan Stan Sakai’s Usagi Yojimbo to life in 2014, thanks to some top-notch costuming and make-up work. So with all that in mind you can understand my surprise when it was announced that Naoki Urasawa and Takashi Nagasaki’s Pluto was going to get a fairly lavish, high-budget stage version courtesy of the Barbican, which played across three dates in the London theatre (originally built for the Royal Shakespeare Company) this past week.

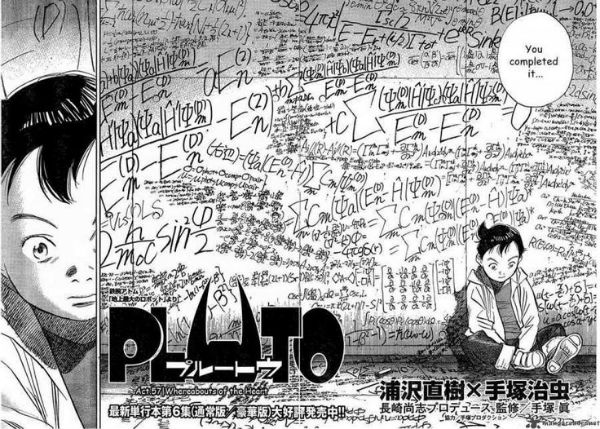

For those unfamiliar, the manga is a modern-day retelling of an old Astro Boy story, a murder-mystery wherein an android detective investigates the killings of some of the most powerful robots in existence, suspecting he and the Mighty Atom (as Astro is called in his native Japan) might be next on the hit list. Typically for Urasawa and Nagasaki’s collaborations, that central conceit is the hook upon which all manner of subplots, side-characters and thematically-appropriate digressions are hung upon, with the eight volume series taking in a huge cast, dozens of locations across several continents, and a number of widescreen action sequences. Which doesn’t make it the most obvious choice for a stage version, especially one pitched at the arty-farty types that frequent the Barbican (I say it with love, or at least self-deprecation, since I am one such membership card-carrying art-fart).

Directed by Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, early signs aren’t great. When the lights come up on the opening scene, it’s to illuminate a succession of panels from the manga being projected on a succession of screens, with minimal interaction from the actors on stage, truncating about 500 pages of tankōbon into a Wikipedia summary-style info dump. It also has to quickly establish the character of Astro Boy for the Western audience, which presumably wasn’t necessary when the play premiered at Tokyo’s Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon. From there we skip straight ahead to the point where Gesicht (Shunsuke Daitoh), the aforementioned android detective, is midway through his investigation, five robots already claimed by this mysterious killer.

Directed by Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, early signs aren’t great. When the lights come up on the opening scene, it’s to illuminate a succession of panels from the manga being projected on a succession of screens, with minimal interaction from the actors on stage, truncating about 500 pages of tankōbon into a Wikipedia summary-style info dump. It also has to quickly establish the character of Astro Boy for the Western audience, which presumably wasn’t necessary when the play premiered at Tokyo’s Bunkamura Theatre Cocoon. From there we skip straight ahead to the point where Gesicht (Shunsuke Daitoh), the aforementioned android detective, is midway through his investigation, five robots already claimed by this mysterious killer.

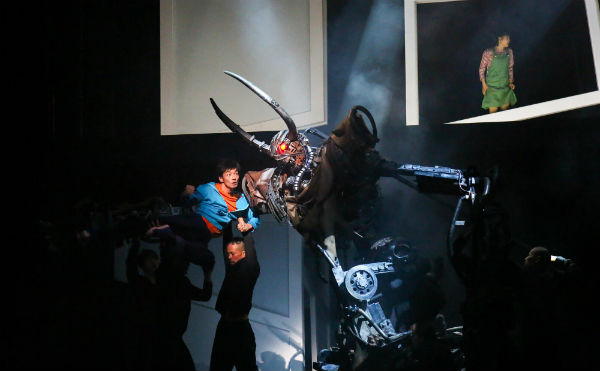

Pluto picks up considerably from that point, the stage opening up and Cherkaoui employing every bit of stagecraft he can think of. There’s rear-projection which transforms the mostly-bare stage into a Middle Eastern bazaar, a rainy Japanese street and a junkyard; modern dance is used for everything from scene transitions to the aforementioned blockbuster fight sequences; there are shadow puppets, recorded dialogue, music, all manner of lighting trickery; and, most striking of all, detailed maquettes utilised for the non-humanoid robots in the story, operated by teams in a similar manner to the beasts in the National Theatre’s noted productions of His Dark Materials and War Horse. All these things combine to make for an incredible spectacle not unlike the stage version of Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night, which has been touring the UK for a few years now.

Meanwhile, rather than simply showing us some Urasawa panels, some of the most effective moments are the ones acted out word-for-word from the source material. Gesicht’s conversations with Brau 1589, a robot imprisoned after being the first to kill a human being, are fantastically eerie, thanks in no small part to the puppet design’s faithful translation from the page. One of the more interesting elements of the adaptation is the constant presence of puppeteers on stage, even when there’s nothing to puppeteer. They stand behind the actors playing Gesicht and his wife Helena, behind both Atom and his sister Uran, miming the pulling of strings and manipulation of their limbs, heightening the sense of difference between them and the human characters, visual representations of the programmes and processes that their machine brains run in order to simulate human intelligence.

Photo by Maiko Miyagawa. © Naoki Urasawa, Takashi Nagasaki, Tezuka Productions

All the digressions often offer up some of the best moments in Urasawa and Nagasaki’s Monster and 20th Century Boys, but they’re digressions nonetheless. By skipping over the subplots in Pluto this adaptation successfully drills down to the core themes, which are actually pretty Shakespearean. Death! Grief! Murder! Fathers and sons! Revenge! War! All that good shit! With its recalling of Asimov’s Laws, the ethics of killer robots and philosophical questions about the soul, it’s also a timely bit of speculative fiction, with a greater depth than recent entries in that sub-genre like (whisper it) Blade Runner 2049. Focussing on these elements which make the play something more than a curio, appealing to those previously unfamiliar with the text.

Photo by Maiko Miyagawa. © Naoki Urasawa, Takashi Nagasaki, Tezuka Productions

Not that Pluto is necessarily for everyone. The similarities between comics and film are striking — both are visual mediums with a unique control over time — but there are notable comparisons to be made between comics and theatre, too. Both require the audience to play an active role in giving the story life. In a comic the story can’t progress until you, y’know, pick it up and read it, but there’s also the tacit understanding that you’ll accept the non-photorealistic drawings of people, buildings, and cosmic rays as representative of the real thing, to believe in this world of abstracted scribbles and speech balloons. When watching a stage production there’s a similar suspension of disbelief required of those watching, to buy into the world in front of you — far easier in film, with the easy distance provided by the screen — when you logically know it’s just a bunch of people reciting lines on a stage a few feet away from your seat. There’s also a fair amount of reading in this performance, delivered in Japanese with subtitles projected on various surfaces on stage.

There were elements of the production the packed house immediately got on board with, and others that appeared to stretch that credulity, like the climactic battle between Mirai Moriyama’s Atom and his attempted killer which takes the form of the dancer being consumed by a large inflated sheet with explosions projected onto it, or the genius AI trapped in the immobile body of a teddy bear who appears to be orchestrating the whole thing. For all that these goofy moments, and the aggressive attempts to not get bogged down in the details of such an epic story, threaten to derail what is already a significant undertaking, the cast and crew pull it off. Against all odds, the universal themes broke through and the performers — who drag first Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and then Urasawa himself on stage to join them in accepting the applause — more than earned their prolonged, bashful bows through a lengthy standing ovation. Next I want to see Maison Ikkoku get the French farce treatment it deserves. Or perhaps an appropriately lavish stage production of Revolutionary Girl Utena…

Review by Tom Baker