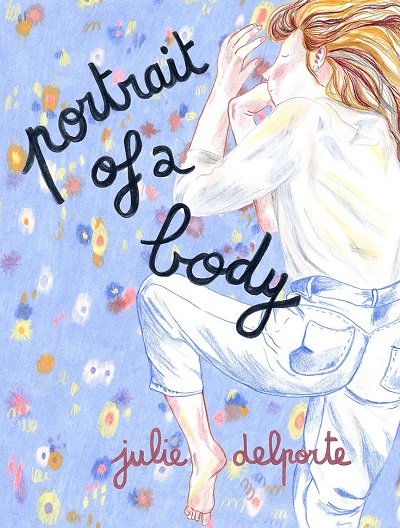

There’s a lot to unpack in Julie Delporte’s new book Portrait of a Body, not only because her brutal honesty may compel readers to address some thorny issues, but because of how she manages to say so much with so little. That her powerful message comes across seamlessly is testament to the care with which Helge Dascher and Karen Houle have translated the original text, as well as to Delporte’s artistic sensibilities. She imbues her delicate watercolours with a lot of symbolism, making second and third readings a rewarding process for anyone so inclined.

Portrait of a Body doesn’t beat about the bush; it jumps straight into how Delporte places herself, her identity as a woman, and her sexuality, within a society that undermines notions of femininity at every turn. It’s interesting to consider how the gender of a reader may affect the way this is read: as a polemic on the need for greater fluidity of gender-assigned roles, or an indictment of how misogyny prevents so many of us from being honest about who we are.

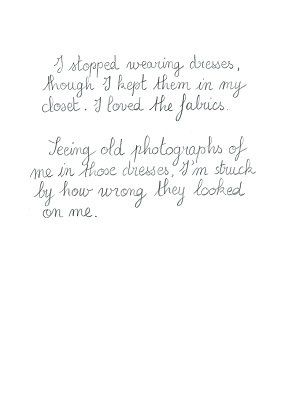

Delporte is brutal when she writes of her youth, the expectations placed upon her at an early age, and how it took her years to come to terms with them. There is much pain here, as well as an underlying anger that drives her narrative forward, and it is all tempered by her careful illustrations of bodies, scenes from movies, and everyday objects that take on layers of meaning via accompanying written passages. Descriptions of how she began looking at the female form, for instance, appear alongside watercolours of flowers that suddenly seem overtly sensual, as if nature has taken its cues from human reproductive organs, or vice versa. There are also the casual (and therefore devastating) references to assault, making this the testament of a survivor, not a victim.

Another interesting thing about Delporte is how she always wears her influences on her sleeve, with afternotes that prompt readers down further rabbit holes. She did this with her last book, This Woman’s Work, referencing British singer Kate Bush’s song about childbirth. This time too, her influences act as a counterpoint to comments about the male gaze, and societal expectations of women. There are specific nods to Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman (her 1974 film Je tu il elle), painters like the American Riva Lehrer and French Rosa Bonheur, the self-portraits of South African artist Zanele Muholi, and even rocks gathered from the beaches on Quebec’s Magdalen Islands.

On page 231, close to the end, Delporte lays bare her book’s premise with moving simplicity: “I am the sum total of everything that has happened to me — the events and the traumas I’ve experienced. I am not unqualified to speak, I am not ‘broken.’ I am simply a reflection of the everyday sexual violence that I grew up with. That we’ve all grown up with.”

Portrait of a Body shows how Delporte’s drawings have evolved. There is still an unfussiness about her sketches, but they are more minimalist, as if she now focuses on the essence of an image rather than its contours. What she leaves out is as important as what she chooses to fill in.

One hopes she will continue to issue missives about her future journeys, both personal and artistic, if only because of what they may teach us about ourselves.

Julie Delporte (W/A) Helge Dascher and Karen Houle (T) • Drawn & Quarterly, $29.95

Published January 2024

Review by Lindsay Pereira

Lindsay, thanks a million for the lovely review. The translation of this work was an incredible and unique experience for all of us: Julie, Helge and me. The stakes felt high and we all needed to get it exactly right.