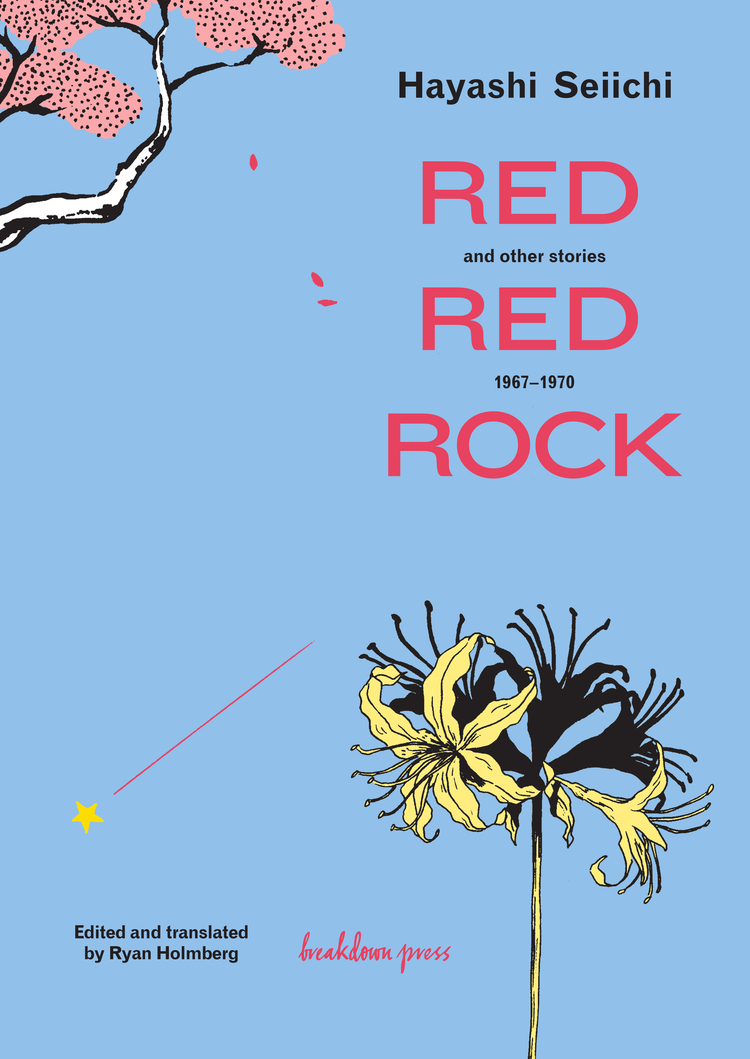

Red Red Rock and Other Stories, a new collection of Hayashi Seiichi’s alternative manga from Breakdown Press, is a demanding but rewarding read.

After 30 years of thumbing (and latterly swiping) my way through the funny books, it’s easy to picture the inside of my noddle like one of those houses on a documentary about compulsive hoarders.

However, every now and then I sit up with a gasp in the middle of the night, my blood turned to ice, as I realise the limits of my “expertise”. For instance, beyond Akira and Lone Wolf & Cub, manga is largely a closed (right-to-left) book to me. And as for avant-garde 1960s manga…

So it was with a mix of trepidation and excitement at the prospect of learning something new that I picked up Red Red Rock and Other Stories – a collection of stories by Hayashi Seiichi from 1967-70, mostly published in the seminal manga magazine Garo and given a 21st-century outing by those subterranean taste-makers at Breakdown Press.

So it was with a mix of trepidation and excitement at the prospect of learning something new that I picked up Red Red Rock and Other Stories – a collection of stories by Hayashi Seiichi from 1967-70, mostly published in the seminal manga magazine Garo and given a 21st-century outing by those subterranean taste-makers at Breakdown Press.

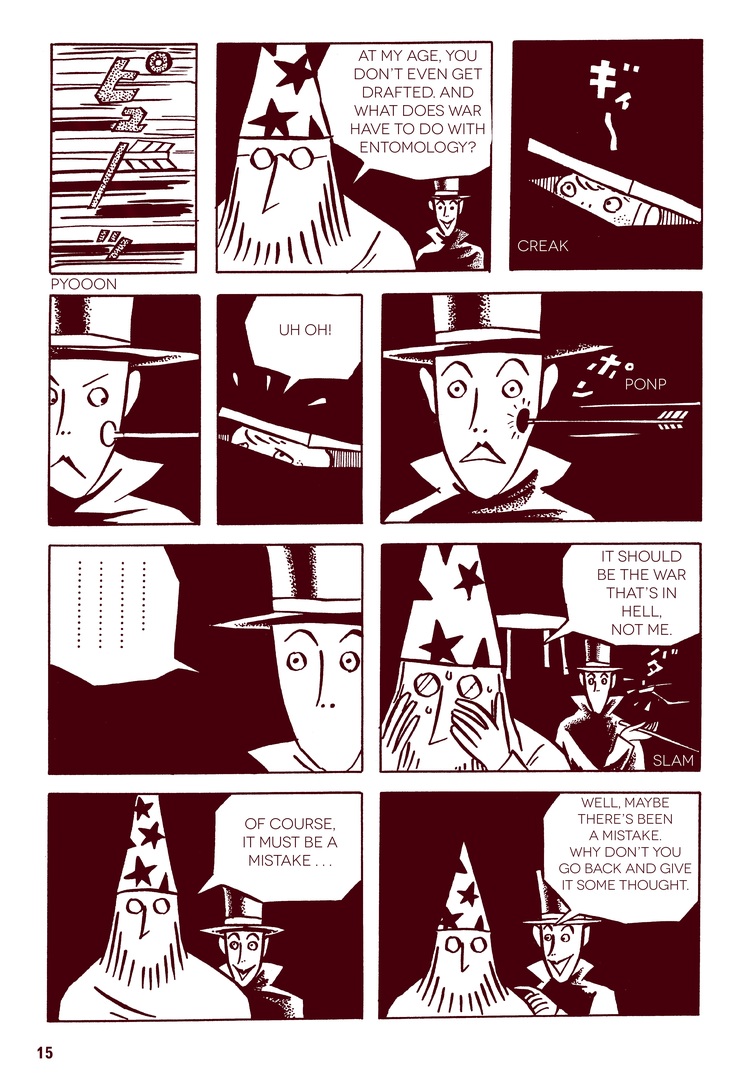

Once you get into the book, you soon realise that you’ve landed in a very distinct part of Planet Comics. Quite apart from the adjustment of reading from right to left, the work is enmeshed in a web of traditions and references that are very specific to another time and place – so much so that despite the clarity of the translation, it still feels at first a little like you’re reading something in a foreign language.

Fortunately, the comics are accompanied by a chunky introductory essay by translator and manga scholar Ryan Holmberg, who admits that the angura (underground) scene of late-60s Tokyo was defined by “intertextuality of kaleidoscopic dimensions”.

(However, while Holmberg’s essay offers something of a roadmap through the stories, even that leaves you wishing for a glossary, as he delves in ever more granular detail into the intricate subdivisions of popular Japanese song and cinema that form a strong underlying element in Hayashi’s work.)

The stories themselves vary in scale and style, and can certainly appear baffling on frist encounter. However, once you’ve acclimatised to the flavour of the work and begin to make the historical and cultural connections, the depth of Hayoshi’s manga pops into sight, like a Magic Eye picture (ask your parents).

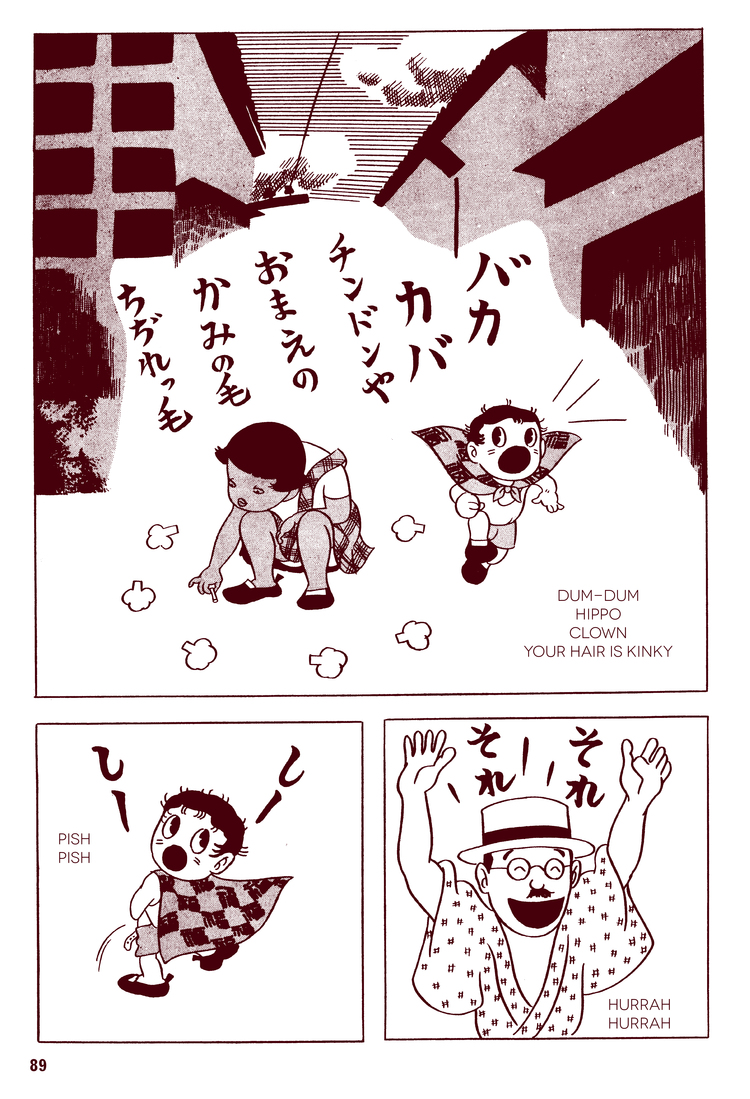

The opening story – The Devil, His Son and the Uneatable Soul – is probably the most straightforward in narrative terms, but by the time we get to Dawn’s Early Light, published three months later, we’re getting into more characteristically challenging territory.

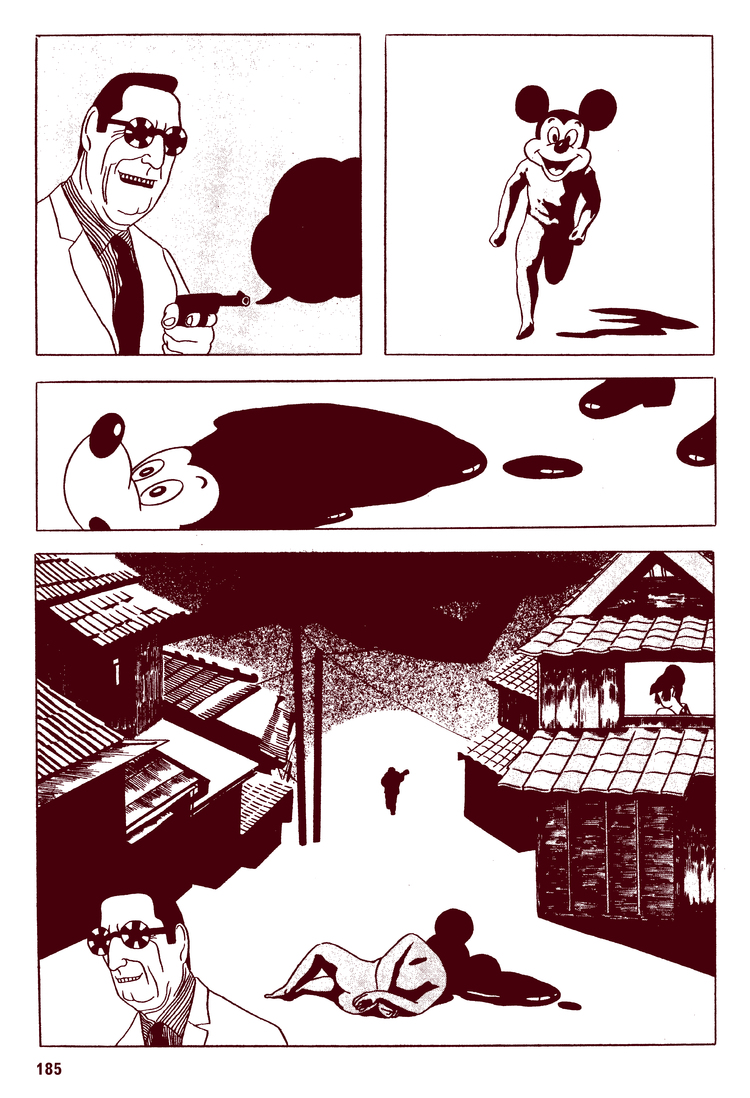

An eccentric take on a US-style superhero, it introduces a few of the themes that play out through the book, including Japan’s complex relationship with the US and its popular culture; a reconsideration of the country’s place in the world; and intense mother-son relationships (reflecting Hayashi’s own experiences with his own mother, whose mental health issues are treated in the story American Born Celluloid).

Those themes are expanded in Our Mother, the first lengthy piece of work in the book, in which a frog leaves home and helps to build an idealised Japanese landscape, pondering the country’s past and future roles and where it should look for inspiration as it rebuilds from the devastation of war, nuclear attack, defeat and occupation.

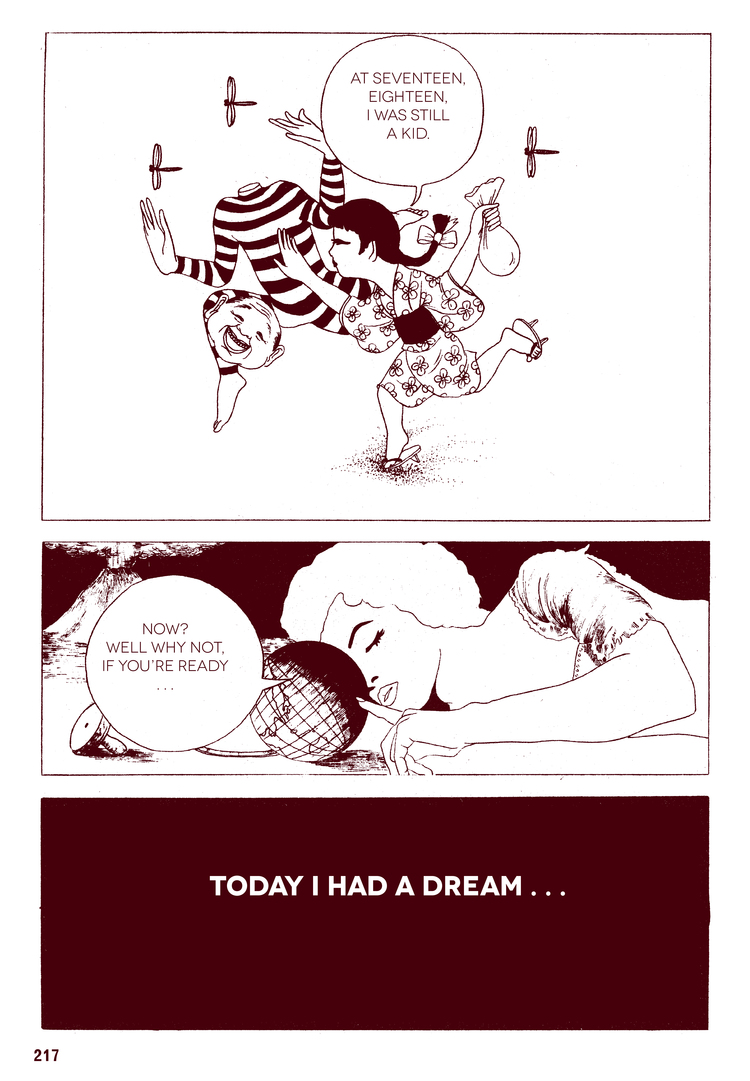

As alluded to above, various forms of traditional Japanese song are woven through the stories, and even if you don’t pick up on the subversive nuances of every reference, the use of refrain-like dialogue and narration gives a lot of these stories a musical rhythm. This is particularly evident in the 50-page story Flower Poem, heavily influenced (in its early pages, at least) by the the Beatles’ contemporaneous Yellow Submarine.

In a telling quote in Holmberg’s introduction, Hayashi praises the energy of the Beatles’ films – in particular the way they suddenly burst into song: “No matter how you edit shots or try to express something in words, you’ll never be able to reproduce that kind of transition. It has incredible power.” And while the ‘silent’ nature of manga stymies Hayashi to a degree, he does what he can to make his pages sing.

Other stories expand on recurring themes. Red Enamel Shoes and Flower Falling Town both deal with the sexual loss of childhood innocence, while the short, lyrical Red Bird Little Bird takes us into the mind of a man haunted by wartime experiences. Gender roles – and their particular state at that moment of Japanese history – also play a key role; two of the stories in the collection were even published in a women’s lifestyle magazine, A Woman’s Self (Josei jishin).

In Flower Poem, women’s tears are a prized natural energy source, to be commercialised and fought over; it’s literally male exploitation and female sorrow that fuels the world. The role of women is also examined in Giant Fish, focusing on what an abandoned wife had to do to survive during her husband’s 26-year disappearance. And Madam D, which closes the collection, is a characteristically oblique treatment of the life of Dewi Sukarno (née Nemoto Naoko), a Ginza bar hostess who married the Indonesian dictator and became a tabloid obsession.

The book spans a variety of art styles, knitted together by the lovely monochrome production in aubergine (?) ink. With a lunge into the surreal and psychedelic never too far away, it ranges from the simplistic cartooning of the opener to the beautifully atmospheric depiction of a bleak snowy landscape (in Giant Fish) and the more complex, pop art-influenced appropriations of his later work.

As you’ve probably gathered by now, this isn’t a book you can pick up and dip into while you’re multi-tasking. And, at first glance, some of the work can be elusive and hallucinatory. However, close consideration of the manga in Red Red Rock and Other Stories pays dividends, taking the reader as close as possible to a singular time and place in comics history.

Hayashi Seiichi (W/A), Ryan Holmberg (Tr) • Breakdown Press, £16.99